Andrew Paul Wood – 27 September, 2010

In some ways, it is a shock to see a contemporary nude in a painting - so many artists today avoid it as a subject, except in the most stylised interpretations, for fear of showing up any weakness in their technique. But one must toast Shennan for returning to the genre. If I was to be critical about anything, it would be that the anatomy of the human subjects is a little crude - torsos seem squashed, heads and feet too large for their bodies. His depiction of the mouth of 'Sing, Chorus, Sing' is positively clumsy, like the gaping mouth of an inflatable sex doll, but perhaps this sort of naivety is deliberate.

The title of this painting exhibition, Ulysses, only indirectly references the cunning Odysseus of Homer’s epic. In fact the exhibition appears to be more themed (albeit loosely) around Irish author James Joyce’s masterpiece of the same name. Some of the included oils have titles like Apollo and Dubliners, or The Dead. Others seem more enigmatic. But let’s face it, the adventures of Stephen Daedalus and Leopold Bloom is one of the most difficult reads in the English language, so anyone attempting to visualise it, especially allusively, has a hard road ahead.

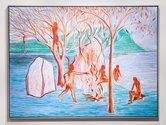

Shennan was born in Scotland, but is a product of Elam in Auckland, and currently teaches at Invercargill’s Southern Institute of Technology. It is difficult to quite know how to contextualise his work. A painting like Giotto’s Rock of Consciousness (I assume it may relate to the “Proteus” chapter of Ulysses with Daedalus on Sandymount Strand, or the rock Vasari says Giotto drew a sheep on, thus changing visual consciousness) contains vague suggestions of David Hockney’s interplay of the human figure and stylised depictions of water; but Ulysses, a sort of bacchanal around a campfire, seems to have hints of Matisse and Gauguin in the dancing figures and colours. The Muse of History could have some sort of distant kinship with Arshille Gorky in his figurative phase.

In other paintings there are whopping great wodges of symbolism or surrealism and what may be esoteric references to alchemy, as in Inside the Vessel; conducting music. At other times I am reminded of quirky illustrators of books and album covers. The paintings are quite flat, and relatively thin on the canvas. The palette is minimal and restrained. The brushwork is smooth and graphic rather than expressive and gestural. Aphrodite, the goddess of love, makes an appearance, as does The Muse of History.

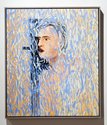

In some ways, it is a shock to see a contemporary nude in a painting - so many artists today avoid it as a subject, except in the most stylised interpretations, for fear of showing up any weakness in their technique. But one must toast Shennan for returning to the genre. If I was to be critical about anything, it would be that the anatomy of the human subjects is a little crude - torsos seem squashed, heads and feet too large for their bodies. His depiction of the mouth of Sing, Chorus, Sing is positively clumsy, like the gaping mouth of an inflatable sex doll, but perhaps this sort of naivety is deliberate. The head disappears into the rapid, frenzied stabs of the brush (a flattened nod to neo-expressionism) and may represent the singing voice. The mouth isn’t particularly unpleasant, and similar effects can be seen in the work of American painter Alex Katz. Edvard Munch’s The Scream might be a distant cousin.

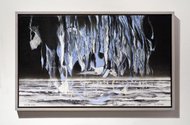

Flames and flamelets are a regular leitmotif in these works, and used as an almost abstract feature. I find the effect quite appealing. Apollo pulls just such a trick, and Dubliners almost does. I rather like Dragon Currents with its all-over patterning and perfectly rendered rain of small flames. It reminds me of Dore’s illustrations for Dante’s Inferno, cantos 12-17, in which the great poet meets his mentor where, as per medieval theology, the sodomites are punished by being forced to run an everlasting marathon through a rain of fire. The painting seems almost abstract in a very pleasing way, another sideways look at a flattened neo-expressionism. The flames are perfect.

No passage in Ulysses leaps immediately to mind, but perhaps it pays to forget all that and just take the paintings on their own merits. Even knowing that there might be a Joyce connection won’t help us know who these people are or what they are doing. Then again, Joyce himself in his use of Homer it might be argued, was pretty much like that.

Andrew Paul Wood

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.