Laura Brown – 3 January, 2013

'Colour By Number' is both the title of the show and the first work seen upon entering the Metro Arts space, running in large white vinyl letters on a dark wall. The title acts as a deft anchor for the exhibition, tying together its many subtle and complex parts. 'Colour By Number' refers to the colonialist system used to sort Indigenous people by the gradient of their skin, with an assigned number that would indicate the field of labour they were to enter.

Brisbane

Dale Harding

Colour by Number

19 Sept. - 6 Oct. 2012

Griffith University Art Gallery

21 Nov. 2012 - 9 Feb. 2013

Dale Harding’s first solo show, Colour By Number, is an achievement driven by subtle force. Whilst finishing his Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art (CAIA) degree at the Queensland College of Art, the young indigenous artist has undertaken apprenticeships under a number of formidable Indigenous artists. One in this list is Tony Albert (also a CAIA graduate), who worked with Harding to curate Colour By Number. The pair have worked together before, most notably on Albert’s huge text work Pay Attention Motherfuckers (2009-10), for which Harding contributed the letter ‘H’. Indeed such a background promises much for this young artist, and his first solo exhibition follows suit.

Colour By Number is both the title of the show and the first work seen upon entering the Metro Arts space, running in large white vinyl letters on a dark wall. The title acts as a deft anchor for the exhibition, tying together its many subtle and complex parts. Colour By Number refers to the colonialist system used to sort Indigenous people by the gradient of their skin, with an assigned number that would indicate the field of labour they were to enter. For young girls this would often mean domestic labour, as was the case for Harding’s grandmother, to whom the breastplate in the exhibition belonged. Unnamed (2012), a thick crescent shape, embossed with this alphanumeric key, is cast in heavy lead and hangs singularly on a bare wall. As with each work in this show, it is potent in its simplicity and effecting with the story which lies behind it, one which is still very much alive.

For Of one’s own country (2011), a rusted ball of steel wool hangs alongside a passage of text which describes the poor treatment and exposure to sexual abuse of young Indigenous women who were sent off for domestic work. Alluding to this history, the rusted ball of steel wool recalls pubic hair. Composed pierced by a needle and silver thread next to this piece of text, it recalls the formal simplicity of conceptual art. In talking about such heavy issues, such subtlety proves to be perhaps the most potent tool for Harding’s work. The things left out are present with just as much volume as those included. Harding’s work needn’t yell to convince. In surpassing the sense of loudness usually present in work with such a strong political background, a pointedness and potency lies in the apparent subtlety and ambiguity of this exhibition.

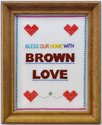

The term Colour By Number may also refer simply to the instructional pattern used to cross-stitch, a medium with a strong presence in this show. The first work using cross-stitch is a series of sheets of thick white paper with simple silhouettes of Australian animals, evoking stereotypical Australian iconography, cross-stitched in clear thread. This thread is almost invisible except for its shininess against the white paper, which itself is almost invisible against the white gallery wall. Here, as the dominating constructs of Australian identity are quite literally made transparent, a parallel history otherwise largely ignored is brought to the fore. These works are particularly poignant with cross-stitch a skill that Harding’s grandmother was taught in her childhood as a part of the domestic labour described above; a skill now passed on to the artist himself. Further, as a man practicing cross-stitch in the contemporary arena, Harding blurs any existing lines within a perpetuation of gender roles.

As with cross-stitch being a skill passed on generationally, Harding passes on significant stories from his grandparents and relatives. Doing so with the specific detail that lies in approaching the topic from a personal history and experience, these works tell the stories of a generation of people usually unheard and ignored. This is reinforced by Harding’s deliberate use of materials and techniques significant to his own history, as well as his personal experience in contemporary life.

Shown later in the year as a part of the series of graduate exhibitions held at the Queensland College of Art, Harding’s newer work no blame rests with them (2012) pushes the potential of this language, to create a sculpture which balances a visual tension with subtle poetry. Again, Harding draws on familial history, using carpentry (as he did with another work in Colour By Number, a large carved needle atop a cross-stitched table cloth) to carve a tall pole balanced at an angle atop two stacked carved milk tins. Perhaps reiterating the strength of Harding’s practice, this work was awarded the 2012 Graduate Art Prize, alongside another CAIA graduate, as a part of the Graduate Art Show, compiled of works specially selected from the graduating year.

Tying this recent body of work together, made up, on the surface, of varying topics, is the domestic setting. This appears first in reference to domestic decoration with cross-stitch, and similarly with the table cloth. This is also present, more gravely, in dealing with the abuse faced by many in the domestic setting for his grandparent’s generation. Underpinning this common thread is the driving intention to bring forward untold stories and oral histories, personal and often familial, which otherwise remain unheard for the general Australian population. In doing so, Harding demands a revision of the telling of Australian history, then sets out to do so himself.

Laura Brown

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.