John Hurrell – 11 September, 2013

The choices made by Conland fit a global theme characteristic of many of her shows, and are all eyecatching outside of their thematic content. One could say the selections are ‘astute' but that would imply Conland is skilled at picking the wheat from the chaff. However I suspect that with Ms Milgrom's acquisition savvy there is no chaff.

Auckland

From the Naomi Milgrom Collection

A Puppet, a Pauper, a Pirate, a Poet, a Pawn and a King

Curated by Natasha Conland

31 August 2013 - 27 January 2014

In this selection from the Naomi Milgrom Collection - housed in Melbourne and built up by the Australian business leader, entrepreneur and collector - AAG curator Nastasha Conland has created a complex show of twenty-two contemporary works, one that due to the stylistic variety and inventive juxtapositions of its six star artists, rewards several visits. And although titled with a throwaway line from a Sinatra song (a list of six character types to match six artists), that’s really a fancy way of going beyond merely saying From the Naomi Milgrom Collection - an attempt to crown the owner’s generosity with the rose petals it deserves.

The choices made by Conland fit a global theme characteristic of many of her shows, and are all eyecatching outside of their thematic content. One could say the selections are ‘astute’ but that would imply Conland is skilled at picking the wheat from the chaff. However I suspect that with Ms Milgrom‘s acquisition savvy there is no chaff.

With this exhibition the linear visitor trajectory - via Martin Boyce, Thomas Demand, Kara Walker, more Boyce, Andreas Gursky, William Kentridge and Wilhelm Sasnal - starts formally with the planar and unmodulated, working through intricate and almost atomistic photographic detail, and finishing with gestural and flourishing mark-making that is still linked to figuration and narrative. And at the start of the Sasnal paintings at the end, Untitled (Anka’s Head) 2010 is a sihouette, looping up with Walker’s film near the beginning. Nice touch.

You might remember that Martin Boyce created one of the highlights of Conland’s 4th Auckland Triennial with his remarkable St.Paul St installation. In APAPAPAPAAK this Glaswegian continues his interest in modernist functionality, lighting systems and linear methods of drawing through sculpture. Boyce has a predilection towards angular planes (butted next to fluorescent lights), and webs of lines that join at acute angles and hint at empty quadrilateral shapes that seem based on a city map. He is an abstractionist who plays with the design conventions of public facilities like telephone boxes, a bit like Liam Gillick with his bus shelters or (in this country) Matt Henry with his ‘office dividers’, ‘heaters’ and ‘fuseboxes’.

Boyce is a bit of a sly humorist. (Maybe it is a Scottish hallmark, if you look at Jim Lambie and Martin Creed too). One bent and angled grille, attached by hinges to the wall, has a cotton undergarment threaded onto a steel strip, placed there before it was welded on. Another work, a ‘painting’ bearing a text of angular steel strips, looks as if it is based on a street map where roads are selected in edited configurations that create letters. Collectively they state ‘A thicket of kisses.’

Thomas Demand is well known for the paper sculptural reconstructions - built 1:1 scale - which he bases on photographs of scenes of crimes or dubious governmental activities, reconstructions he photographs in colour and then destroys. These beautiful planar simplifications eschew human figures or any kind of detail, and look oddly like modernist paintings (like say, Picabia) with their flatness, geometry and rhythms. The three photographs he contributes allude to the Bush administration’s calculated circulation of lies about the Saddam Hussein administration, as well as the activities of the German Parliament, and the storage problems of the National Museum. He has a tendency to hold information back, and even when he does publish texts, their content is still oblique, like his images which contain no words anywhere.

With the cut and folded paper sheets suggesting solid masses, there is a hint in Demand‘s imagery of the world of surface, perhaps the Vedic concept of Maya, saying that the real world is actually illusory. There is also a host of other possible interpretations of these images, especially when focussing on paper as metaphor for the transmission of information in a pre-digital age. Because the correlation is not quite perfect, and the planes exude a subtle thinness, with edges a little crooked, all surfaces look fragile and vulnerable.

Kara Walker‘s video is a filmed play using paper silhouette puppets back-projected on a screen, their movement and swivelling arms controlled by attached sticks. Set in a southern plantation - with the main characters consisting of a slave woman, her son and a plantation owner - the jerking bobbing shadows communicate a narrative that is violent and shocking on a literal level but which can also be understood in Freudian symbolism. Acts of forced penetration, amputation, symbolic castration, burial, and affection overlap and move in sequence, so that you are never really sure what is actually taking place and what is metaphorical.

What is fascinating is Walker’s comparatively clumsy method - with its mixture of different coloured shadows, distorted shapes, floating forms, and manual manipulation. It is anti-slick yet profoundly disturbing. The video work seems so different in mood from her more well-known silhouetted murals that are overtly illustrational and tidier. The film embraces confusion as if it’s a trope for the messy contingencies of history itself.

Andreas Gursky is famous for his use of digital technology to cram a plethora of extra morphological variation and very intricate detail into his frame - or else remove it. His three massive, astoundingly dense photographic images feature the New York Merchantile Exchange, Los Angeles by night and a very large display stand of Prada running shoes. The themes of the greed of Wall Street, the global reach of Hollywood, and US consumerism are very much of our time, and are a nice foil to the related but more intimate works by Demand. The unusual scale in relation to the visitor here has photography physically affecting the viewer in much the same way as a very large painting might, except the print and covering glass are highly reflective.

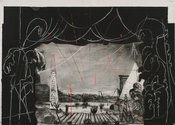

The work of William Kentridge has been presented several times in Auckland, particularly in the Gus Fisher and Auckland Triennials, but the works here (three drawings and an anamorphic film projected on the sides of a tin) are full of surprises. The charcoal and chalk drawings look like working sketches for projects involving opera, and depict stage sets, while the best looks at a row of staggering pylon forms (towers with people inside them), one of which is a thin version of Tatlin‘s famous planned Monument to the Third International (1917).

What Will Come, the 2007 film, is a real treat, projected from the ceiling onto a round table so that it bounces coherently onto the centre-placed vertical can. However the turning elongated distortions on the table’s perimeter are distracting decoys for this narrative about the 1935-36 Italo-Ethiopian War, and Mussolini’s invasion. It’s best to keep your eye firmly on the tin where the moving rubbery forms become compressed, resolved and comprehensible.

Next door, the final room at the end presents seven oil paintings by the acclaimed Polish artist Wilhelm Sasnal. It is the first time to my knowledge that Sasnal has ever been shown in this country: an amazing oversight considering the quality of his images. His work tends to be graphic and favour black, white and grey, with chromatic colour carefully restrained when added, and all his examples here are interesting. He has a real flair for paint handling while there’s a strange black humour in a lot of his work. When not humorous, it’s plain sinister.

Sasnal seems intrigued by deformity or malfunction, but often incorporating a peculiar wit that is hard to nail. One image of a man’s head in profile has a distinctive burn or scar branded onto his neck. Another is of a passenger jet that has no wings and a rubbery banana-ish bend - as if an ultra long penis - but resting on a huge wall. The line of windows becomes a sort of zip.

Other works are deadly serious. One image of a plane, the triangular Concord, seems to be about carbon footprinting. Another of railway tracks leading off into the distance, bordered by trees with their branches trimmed off, I suspect refers to Nazi concentration camps and genocide. One other still, of Robert Oppenheim and his brother standing by their car, speaks of the bomb and the guilt of certain individuals necessary for its construction.

With its carefully orchestrated - finely considered - hang, this is easily the best contemporary art show presented so far in the revamped AAG building. You pinch yourself when seeing such a superb group of international works in Auckland. It’s very special.

John Hurrell

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Here is an interesting article on the Melbourne collector, Noami Milgrom: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/naomi-milgrom-art-collector-australia-2421402

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 11:04 p.m. 23 January, 2024 #

Here is an interesting article on the Melbourne collector, Noami Milgrom:

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/naomi-milgrom-art-collector-australia-2421402

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.