Peter Dornauf – 8 November, 2020

It was Nancy's unique hairstyle, a stylized blob with nodes attached, that first attracted the artist as a feature and form he could work with. In Watkins' hands, cartoon components meet the formal elements of abstraction, courtesy of Miro and others, a marriage made in New Zealand, and modest in size.

The history of abstraction comes with a load-bearing weight from past generations of practitioners, practicing various forms of high seriousness—the search for purity, the pursuit of the absolute, expressions of metaphysical angst, the unloading of melancholic spiritual meditations, the opportunity to give manifestation to the shape and swish of the heroic brushstroke.

We, in these islands, had our small share of this phenomena, but given the pragmatic, down-to-earth and phlegmatic kind of people we are—not given over to too much philosophical or mystic contemplation (and enjoying some light relief through the arrival of Pop Art)—it didn’t come as a surprise that we should witness the birth here, post 1970, of an art characterized by Denys Watkins, depreciatively, as “lightweight.”

Watkins has for a while, in the last two decades in particular, been interested in abstraction. More Paul Klee than Colin McCahon, he quipped at the opening of his show, Nancy’s Big Day Out, now on at Weasel Gallery.

The title immediately gives the show away. Nancy is the playful, impish and bright little eight year old Nancy Ritz: brainchild of American cartoonist, Ernie Bushmiller. She made her singular debut in 1938; and her “big day out” operates for Watkins as both a mocking reference to the palaver of august exhibition openings and perhaps, the bigness associated with abstract art and its overblown rhetoric.

It was Nancy’s unique hairstyle, a stylized blob with nodes attached, that first attracted the artist as a feature and form he could work with. In Watkins’ hands, cartoon components meet the formal elements of abstraction, courtesy of Miro and others, a marriage made in New Zealand, and modest in size.

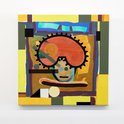

It features prominently in Heatwave, together with a plethora of abstract notations-biomorphic and geometric with pieces of gingham thrown in for good measure—straight off Nancy’s dress. This is all good fun. Forms protrude, overlap, congregate, play flat, sometimes assume 3D dimension, shadowed, secured or floating, possessed of colours that have a definite 1950’s retro look. Indeed from a certain angle, the whole conglomeration of abstract forms takes on a rather domestic setting, perhaps suggestive of a table top, tilted 90 degrees. What holds the whole thing together is the gridded background which gives the appearance of lino flooring.

One is reminded here of graphic designers from the high abstract period who were inspired by the American Abstract Expressionists and employed their forms, albeit in a reductive manner. For example, the skater lines on lino flooring of the fifties that took their inspiration from the splash and dash dribbles of Jackson Pollock.

Watkins returns the favour by working it in the opposite direction, taking the banal and turning it into ‘high’ art. Such cross fertilization, with all the layering involved, provides spark and fizz while reminding the viewer to keep a level head. Elements of irony abound.

What seems to have attracted him to this particular cartoon strip is the fact that Nancy has a cheeky iconoclastic attitude, aimed at times at the art world itself. In one strip she is depicted with a fishing rod standing outside a “Museum of Art” window, dangling one of her own painting inside it, with the express purpose of being able to tell people that her work “once hung in the museum.”

While Watkins’s own works regularly hang in “Museums of Art”, with all the kudos that comes with that, he obviously enjoys the levity and satire inherent in the Bushmiller’s mischievous contrivance.

That kind of mischievous ‘impertinent’ light spirit is demonstrated in the titles Watkins gives his works, completely eschewing any pretentious attempt at a contrived gravitas. He calls on a whole world of popular culture, in particularly that of jazz and blues, when he titles his works Thumbelina, La Vern, Maybelle, Mamie, Bessie, Wanda and Angela. The latter goes a little deeper with its reference to Angela Davis, American political activist and author, while Fifth Column picks up and runs with that, perhaps a sassy allusion to himself and his art practice. The man can certainly identify with Nancy Ritz and her feisty attitude, complimented by the improvisation of his formal elements that jostle for position on the canvas.

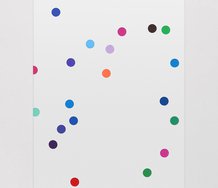

This is Denys Watkins’ Big Day Out. A fun time was—and will be—had by all, as one takes in the view of Frisky with its echoes of Leger, together with Angela (with its hot dog amidst strict geometry), or Fifth Column that includes the smallest hint of a Walters koru. There is also Thumbelina, which has the last say on the hair motif, its nodules becoming detached and taking their independent place—like ants’ eggs among the circles, oblongs, squares and diagonals—mixing and mingling between the sharp edged outlines and more undulating random forms by turns. Inventive, witty and exuberant.

Peter Dornauf

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.