Norman Franke – 10 September, 2022

In both Christian lines of tradition, both in Eastern and Western art, artists have wrestled with the old prohibition on images from the Tanakh's/First Testament's Decalogue in their depictions of saints and the deity. In addition, the biblical ban on images involves another profound theological consideration: In Gen 1.27, this seminal early expression of human dignity and equality, the 'imago dei' (the image of God) is attached to the image of all human beings, women as well as men. Any specific humanoid depiction of God must necessarily miss this pluralistic periscope which is expressly gender inclusive.

Auckland

120 selected works

Heavenly Beings: Icons of the Christian Orthodox World

15 April - 18 September, 2022

It was a wintry day in normally mostly subtropical Auckland, the temperatures at night went close to freezing point, and the Hauraki Gulf was the Baltic Sea off Vasilyevsky Island in St. Petersburg. My wife had whisked me away to a nice Auckland hotel near the art museum, the Auckland Art Gallery [1], for a birthday weekend.

The Art Gallery is a special highlight of Auckland. It currently shows an important exhibition of Orthodox icons (Heavenly Beings. Icons of the Christian Orthodox World) [2]. The core of the Auckland show is a collection on loan from Canberra, supplemented by various pictures from New Zealand—there’s more of them than one might think. Around 120 paintings and objets d’art can be seen in Auckland.

As I walked through the exhibition rooms on a Tuesday morning, very few other visitors crossed my path. Perhaps at the moment the icons are being too closely associated with Russia à la Putin. Putin does indeed have close ties to the Russian-Orthodox metropolitan bishops and the Patriarch of Moscow and all Russia, Kirill, who is estimated by Forbes to be 4 billion US dollars worth [3]. Kirill has repeatedly tried to theologically justify Putin’s murderous attack on Ukraine [4]. Since February 2022 large parts of the Ukrainian Orthodoxy, but also Orthodox communities in the West, e.g. in the Netherlands, have renounced the Moscow Patriarch. Pope Francis tried to appeal to the Muscovite clergy; and so did the New Zealand minister, interfaith activist, former director of the International Center for Reconciliation, Paul Oestreicher, who was driven into exile by the Nazis as a child [5]. In an impassioned article in the Guardian Paul Oestreicher spoke out against Putin’s war and the war theologians in Moscow [6].

The icon portraits, including many from the Greek Orthodox sphere including Crete, Cyprus, and Albania as well as the ancient African orthodoxy in e.g. Ethiopia are often of such great depth, that, a few exceptions not regarding, they are at odds with power politics and any sensationalism of the postmodern attention economy. A lot of the icons also reminded me of naïve art that I saw as a child at Rolf Italiaander’s ethnological collection [7] on the outskirts of St. Petersburg’s German twin city Hamburg. It is often the folksy images, created and invoked from everyday life, that are particularly impressive.

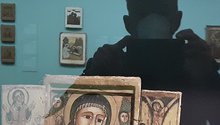

I wanted to photograph some items, because unfortunately my vision is getting worse and some details of the pictures shown in Auckland are easier to see through the cellphone camera than with the naked eye. I also intended to take some motifs home for my own artistic reflections and perhaps adaptations. Plus I took some photographs simply as souvenirs.

Due to the lighting of the icons with ceiling spotlights, however, my shadow or reflection pushed itself into the visor again and again. At first I tried to circumvent this and somehow squeeze myself to the side of the frame in order not to create any shadows or mirroring. But then I decided to allow these involuntary multiple layers of images to happen and even to include the shadow of me as the photographer in the shots. In the end, I deliberately chose the reverse option of the cellphone: the result was a series of ‘selfies with saints’, of which I am attaching a few examples in the image section of this essay.

It was a somewhat hybrid experience to making these photographic recordings: exhilaration through the arranging, balancing and artistic capture of the icons—but also some shame about something like committing a postmodern digital sacrilege, since in the tradition of icon art it is assumed that the images of the saints and the sacred templates (e.g. in the icons relating to the ‘true face’ of Christ, the Mandylion of Edessa [8]) preserve a reflection of the aura and holiness of the saints and witnesses. Orthodox icons, but also Western devotional images, are in a special way subject to Walter Benjamin’s dialectic considerations on Art in the Age of mechanical Reproduction [9]. On the one hand, the photography of works of art is potentially an act of their democratisation; on the other hand, the technical reproduction lacks the immediate encounter and meditative appropriation of the work so it usually robs the images of their aura and mana [10].

As I was taking the pictures, I also realised that these portraits of saints on display in a museum (rather than in a church or family shrine) had already been taken out of their devotional framing and their original setting in everyday or ecclesiastical life anyway. Arguably very little of the pictures’ theological programme is immediately accessible to most Western and Polynesian visitors, and it is therefore advantageous that all icons on display are meticulously commented on. The attached comments are expertly, yet accessibly, written by chief curator Sophie Matthiesson and her team. All of this: the spatial, temporal, museo-scientific distance to the icons’ auratic places of origin is almost inevitably part of the reception experience in Auckland, so much so, that I finally decided that my hybrid photographic approach with the digital camera mainly emphasised an already multiple mediated viewing experience through some additional staging.

My hope is that the photographs also contain an element of sublation, preserving and elevating essential aspects of the images. Nonetheless, the process of electronically preserving images of historical icons does not only expose an undercurrent of multilayered reflection, but, in the visualisation of holiness through modern technology, confronts the photographer with the hubris and hybridity of (post-) modern memory and reproduction techniques. As a photographer, I noticed with a somewhat shameful melancholy that this intimate theological, even mystical art is no longer directly accessible today.

Andrei Tarkovsky‘s hauntingly beautiful film about one of the greatest icon painters, Andrei Rublev, my old Petersburg friend Alexander, and the war in Eastern Europe brought me here. Andrei Rublev (1966) is a cinematographic theodicy, an arthouse film as a chronicle of artistic suffering and yet a celebration of life after the destruction of people and culture by murderous barbarians [11]. Tarkovsky was a Russian patriot and while I was walking through the Auckland exhibition I speculated, and was almost convinced, that, if he had lived, he would have spoken out and worked against Putin.

With Tarkovsky’s film images in mind, I was scanning the Russian icons of the Auckland exhibition for signs of that deep, secret Russia that exists beyond the delusion of the murderous dictator in the Kremlin. Next to and together with this ‘mystical Russia’ I imagined a ‘mystical Ukraine’ closely related to Russian through language, writing and religion, yet independent and free. The conversion and baptism of Olga in 950 CE—later venerated as an Orthodox saint—and the 1030 CE mass baptism in the Dniepr under Vladimir I, a Varangian in Kyiv, gave birth to the Orthodox Church in what is now Ukraine and Russia. For centuries both were closely aligned with Eastern Christianity in Constantinople. [12]

The grand old Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv [13] with the mosaic icon of the praying Mother of God (Orans, ca. 1000 AD) and the venerable Kyiv Pechersk Lavra [14], a seminal monastic community which according to legend was founded by a monk from the Greek Athos, are main sites of Christianity in the East and World Heritage Sites. As early as the Middle Ages and then increasingly after Peter the Great, the Russian Orthodox Church supported the feudal system headed by the tsars. As in the West, the orthodox state church contributed ideologically and practically to the oppression of religious minorities such as Jews and Muslims; and only towards the end of the last century were there timid beginnings of ecumenical and inter-faith dialogue.

Tarkovsky left the Soviet Union in 1984 and then effectively worked as an exile film maker in the West. Always labouring on the brink of exhaustion, he soon had to visit an anthroposophic hospital in Germany. A persistent rumour has it that his unusual cancer was not only caused by stress and homesickness but also by the intervention of the KGB; and he died at the age of 54 in Paris. Already terminally ill but with the help of the Swedish actors and friends of Ingmar Bergman, on the island of Gotland, Tarkovsky produced the film that contributed to the end of the arms race of the Cold War and may have helped to avert a nuclear disaster in Europe: The Sacrifice / Offeret [15]. Not long after Glasnost began in Russia, many Russians, including top Soviet officials and Gorbachev supporters, saw the film—and many were so impressed that they accelerated initiatives to end nuclear buildup and the Cold War. The first Russian viewers are said to have been in tears while watching the film.

A contributing factor may have been that Tarkovsky had to shoot the film’s dramatic final sequence twice: the burning down of a two-storey house by the sea (an oikos, gr. for house) which symbolised the sacrifice that was to ensure the survival of living ecology, the continuation of natural and cultural history. During the first shoot of the burning oikos, the camera was blocked while the flames were devouring the building. With the film’s budget already massively overdrawn, Tarkovsky had little reserves of finances and energy left. But he refused—as he had been advised by the film producers and some friends—to have a scale model of the house built and then incinerate it again. Borrowing money from his friends, Tarkovsky had the house rebuilt to its full dimensions, only to set it ablaze again for the film’s final scene [16] . Such was the passion of the man who believed in the sacredness of art. Tarkovsky’s tomb at the Ciemetiere Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois features an icon reminiscent of the great protective image of Our Lady of Kazan [17], which inspired many images that can be seen in Auckland.

Andrei Rublev and the other great icon painters created platonic, archetypal, onto-theological art that seems to transcend criticism, irony, and deconstruction. In contrast to (post)modernist aesthetics, there is absolutely nothing about this old ecclesiastical art that is satirical, mordacious or frivolous. Many, if not most of the Auckland icons were meant to be references to and anticipations of a serene defeat of a broken, alienated, morbid world. Even the depicted orthodox religious warriors, e.g. Saint George, Demetrius, Procopius, are usually depicted in the pose of serene victors or conquerors; their slaying of dragons and demons seems mostly an easy, almost relaxed exercise. Depictions of the young Christ as Emmanuel or as world ruler (pantocrator) are deeply imbedded in the discursive history of (neo-)Platonic aesthetics and Johannine theology. The same applies to aspects of the representation of Mary as the mother of God (Theotokos), which ties in with ancient hermetic ideas of Sophia (gr. sophia means wisdom), as a female-connotated wisdom seen as one of the cardinal qualities of the divine. [18]

Some icon representations from the life of Mary, especially in the representations of the Annunciation, the Pieta and the Transfiguration of Mary, show more worldly, corporeal, and ‘psychological’ elements. Occasionally some great artistic wit or mischievousness comes through in the icons, e.g., in the pictures of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem: The trees shown in the background contain children who have climbed into the branches as spectators [19], reminiscent of the Zacchaeus story, but also of an anarchic paradise, or of triplets in a placenta. And yet one can easily discern that, especially from the 15th century onwards, the difference between Western (Latin-Catholic, but above all Protestant) and Orthodox pictorial discourses regarding the visualisation of the divine could hardly be greater. While in the West, as in the case of Aelbrecht Bouts (Man of Sorrows, ca. 1490) [20], Matthias Grünewald (in the crucifixion scene of the Isenheim Altarpiece, ca. 1516) [21] or Mateo Cerezo (Ecce homo, 1650) [22], a concrete, even hyper-realistic, sense of corporeality, an almost anatomic depiction of God’s incarnation prevails as an incarnated human being, in the Orthodox image discourse an archetypical, cosmic, harmonious image of Christ is dominant. Christ still displays a human, sometimes almost androgenic, face but has transcended the sphere of mortals and the corporeal.

In both Christian lines of tradition, both in Eastern and Western art, artists have wrestled with the old prohibition on images from the Tanakh’s/First Testament’s Decalogue in their depictions of saints and the deity: “Thou shalt not make a graven image”. Although this ancient prohibition may originally have referred to sculptures, the commandment has been repeatedly extended to paintings as well. The target of the ancient Israelite theologians was idolatry. In terms of the aesthetics of reception: as worship and service of false gods, but also in terms of production aesthetics: as a waste of creative energy on fetishes and idols. Idolatry was seen as a danger which enslaved both the idol worshiper and the idol maker to the depicted objects: they were to be spiritually drained by the mute, insubstantial and ineffective idols supporting exploitative and mundane interests. In addition, there was the philosophical consideration that a finite creature (man) could not adequately represent an infinite creator (God), and that the attempt alone was an act of arrogance, or worse, hubris to a role reversal between God and man.

In addition, the biblical ban on images involves another profound theological consideration: In Gen 1.27, this seminal early expression of human dignity and equality (“God created man in his own image; in the image of God he created him. Male and female he created them.”), the ‘imago dei’ (the image of God) is attached to the image of all human beings, women as well as men. Any specific humanoid depiction of God (God as ‘Father’, as ‘King of Heaven’ and judge, male, with beard, etc.) must necessarily miss this pluralistic pericope which is expressly gender inclusive.

In Western religious pictorial traditions, the Son of God, Jesus, is often depicted as the outstanding human in which God shows his face and takes upon himself human destiny. Precisely in its particularity, pars pro toto, the concrete references to the life and death of an exceptional human being become representative. In the Eastern Church, on the other hand, the iconographical emphasis is increasingly on Christ, the ‘New Adam’, in whom the ‘Fall’ and the suffering of the world have been overcome. This Christ image is also a representative figure, but as general or arche-typos. As it were amalgamated, he is the idealised image of the fusion of all the christened, of all saints, a visualisation of Pauline Corpus Christi (mystical body of Christ) theology. At the same time, especially in the pantocrator images, he is an emanation of the triune deity, which is particularly emphasised in Eastern Orthodoxy.

While I was taking my ‘Selfies with Saints’, a loop of orthodox monastic chants played in the Auckland exhibition of Heavenly Beings. It wasn’t until I got home to Hamilton that I looked at the cellphone photos—and while I was editing them, I listened to the recording of Tchaikovsky’s Hymn of the Cherubim (1878), a setting of the ancient Cherubicon based on the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom [23].

The liturgy makes explicit reference to the spiritual, ‘representation’ or musical ‘depiction’ (‘ikonízontes’) of angelic music: “I tá Cheruvím mistikós ikonízontes,/ ké tí zoopió Triádi tón Triságion ímnon prosádontes,/ pásan tín viotikín apothómetha mérimnan.” // “We who mysteriously depict the cherubim/ and sing the life-creating Trinity with the hymn ‘Three times holy’—let us now lay aside all cares of everyday life…” Tchaikovsky’s hymn is one of those mysterious musical works that give a foretaste of a metaphysical, sidereal sphere; and nobody pulls it off as impressively as the members of the old USSR Ministry of Culture Chamber Choir [24], who, because of their ideological ties to Marxism-Leninism, were all ‘officially’ philosophical atheists. I then read about the current situation in Ukraine in the Guardian. And an old poem came to mind:

Zooming in on a Russian icon

an old and holy man appears

who, behind the back

of Herodion of Patras

and the Archangel Selaphiel

gets beaten up.

Dressed like a Roman legionary,

the aggressor tries to find support

for his knee under the tunica

trimmed with hyacinth blue. Above,

in a narrow grey room of clouds

hovers the Pantocrator

staring mortified

into the distance. [25]

Norman P. Franke

[1] https://www.aucklandartgallery.com/20/08/22

[2] https://www.aucklandartgallery.com/whats-on/exhibition/heavenly-beings-icons-of-the-christian-orthodox-world?q=%2Fwhats-on%2Fexhibition%2Fheavenly-beings-icons-of-the-christian-orthodox-world 20/08/22

[3] https://www.forbes.com/2009/02/20/putin-solzhenitsyn-kirill-russia-opinions-contributors_orthodox_church.html?sh=59e15e983bf9 20/08/22

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/apr/03/the-guardian-view-on-the-russian-orthodox-church-betrayed-by-putins-patriarch

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Oestreicher

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/08/patriarch-kirill-has-betrayed-the-christian-faith

[7] http://www.museen-sh.de/museum/DE-MUS-060017 20/08/22

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image_of_Edessa

[9] Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit (erste deutsche Fassung, 1935) in: Walter Benjamin: Gesammelte Schriften. Band I, Werkausgabe Band 2, herausgegeben von Rolf Tiedemann und Hermann Schweppenhäuser. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-518-28531-9

[10] This Polynesian term, which was theorised by Lévi-Strass and Hartmut Böhme, among others, seems particularly pertinent here. It designates prestige, aura, nobility, charisma, but is always associated with a place, a time-space and the viewer’s or user’s deeply held beliefs.

[11] https://www.imdb.com/video/vi2806824473/?playlistId=tt0060107&ref_=tt_ov_vi

[12] For a more detailed analysis of these cultural and religious links s. Evans, Helen C.; Wixom, William D. (1997). The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843-1261. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Sophia_Cathedral,_Kyiv

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kyiv_Pechersk_Lavra

[15] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ODJb2-PLu7Y

[16] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3S_G8RBVZQ

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrei_Tarkovsky#/media/File:Gravestone_of_Andrei_Tarkovsky_2007.jpg

[18] Many illustrated examples of the theological and liturgical functions of icons throughout the ages in: Alfredo Tradigo (Stepen Sartarelli tr.) Icons & Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum 2006.

[19] S. the detail of a Novgorod-style icon (characterised by the light, off-white or ochre background) in the picture gallery of this essay

[20] https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q27565352

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isenheim_Altarpiece#/media/File:Grunewald_Isenheim1.jpg

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mateo_Cerezo#/media/File:Mateo_Cerezo_d._J._001.jpg

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liturgy_of_St._John_Chrysostom_(Tchaikovsky)

[24] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SZQzW_QfPew

[25] Norman Franke, ‘Beim Zoomen einer russischen Ikone’. In: Lyrik der Gegenwart 71, EDITIONARTSCIENCE, St. Wolfgang, Österreich, ISBN 978-3-902864-78-9, p. 66 (original in German)

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.