Mark Amery – 28 February, 2010

Like a cut-up hypertext collage of quips, quotes, notes, asides and journal entries across time, it makes no clear linear sense. Shuffling forwards and backwards in time, it's reminiscent of some '70s-'80s sci-fi film prediction of future communication.

One of the sadder characteristics of film-based contemporary art has been its lack of attention often to the dramaturgy of storytelling, and the viewing structure provided for its reading in the physical gallery space. It’s been noteworthy that the strongest exhibitions of video art in Wellington for me in recent years (rather than single works) have been from ‘70s pioneers in this field. Darcy Lange at Adam Art Gallery, and Phil Dadson, Gray Nicol and now recent British immigrant Jeremy Diggle at the Film Archive. These are artists who seem to understand their work has to be articulated within a space as a whole readable construct. Not just whacked into a DVD player playing into a monitor on a plinth, or on the floor. Art students would do well to spend more time examining presentation and structure - the actual mechanics of introducing something to a viewer - and less on writing that seeks to explain the work’s theoretical underpinning.

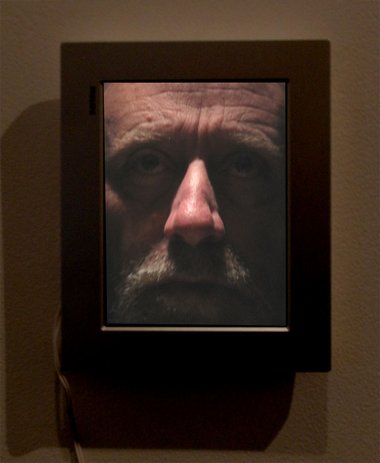

This is the great strength of Jeremy Diggle’s installation Narvik’s Complaint. Structurally it’s as fascinating in its complexion as a strong painting, drawing you into an engaged exploration through text and image with self portraiture disturbed by shifting space and time. Head of the School of Fine Arts at Massey (and previously briefly at ELAM), while Diggle’s practice extends over thirty years, this is I believe his first New Zealand exhibition.

Diggle has a particular interest in viewing mechanisms. I wrote the following for a feature on him for magazine Massey Research last year (available in full online at the ‘profile’ page of www.diggle.info), which provides as good an introduction to his work as I could rewrite:

“An image capture of Diggle’s art practice and research areas at any one time suggests a rich and fractured - nay eccentric - content, reflective of Diggle’s interest in experimenting with visual language in order to create complex narratives. The hypertext structure of the online world suits him well; his adventurous, inquisitive mind ensures his world is one under perpetual reconstruction.

“From reenacting the Apollo 11 moonwalk to studying the painting techniques of Vermeer, Diggle’s work as an artist and researcher defies easy classification. “I suppose I’m deeply anarchic,” he comments to me at one point. Yet on consideration there are very strong threads through both his art and research work. Diggle’s international reputation rests with being at the vanguard of using new technologies, from video in the 1970s to holography and multimedia. Ultimately however he says he is most interested in how we tell stories or construct narratives.”

Narvik’s Complaint contains a blog component and there’s a youtube clip of its central altar-like video work. But an understanding of the work’s full dynamics really only comes from visiting the gallery.

Taking the principles of the Large Hadron Collider as its base, it explores what would happen if your 2010 self could engage in internal conversation - in a kind of collision through memory - with your younger self. In blog and exhibition Diggle sets up a conversation through an often baffling collage of text and photographic fragments between himself now and himself in London as a young artist in the mid 1970s.

The Large Hadron Collider lies in a 27 kilometer long tunnel beneath the French and Swiss border. It is the world’s largest high energy particle accelerator, with thousands of magnets being used to collide protons at phenomenal speed to try and answer unsolved fundamental questions of physics in terms of the structure of space and time. Shut down several times since it began a few years ago it resumed operation just this month. Perversely, Diggle has stopped and restarted his project to realign with this. Narvik’s Complaint is essentially about the impossibility of being in two different places at once - what scientists are trying to achieve with the LHC.

Entering the gallery you are greeted by a computer monitor flashing you back in time somewhere between Diggle’s then and now. On screen is a facial icon make out of a floppy disc drive slit for a mouth and two monitor screens for shades (Diggle breaks reverence with humour at regular intervals). The artist’s dim reflection can be seen in the screens, resembling some raptured inventor, and ghost in the machine. Below the face a textual interchange is going on, typed out character by character in a range of idiosyncratic fonts, colours and caps (a kind of theatrical duologue). Like a cut-up hypertext collage of quips, quotes, notes, asides and journal entires across time it makes no clear linear sense. Shuffling forwards and backwards in time, it’s reminiscent of some ‘70s-‘80s sci-fi film prediction of future communication.

From here you move towards the central work on the back wall along a corridor of four groups of five small portrait shaped screens - suggesting a shifting of time, the collider tunnel, the panel presentation of narrative scenes in a church, and an airplane’s passenger windows. This sense of physical travel is echoed by the occasional use of images of the sky flying above the cloudline within the frames.

These digital photo frames shuffle as slideshow overlaid images and text. The core images are a 360 degree recording of Diggle’s present living space, featuring numerous props and mementoes, such as a model of a house and an arm. These speak symbolically to his glimpsed past. Overlaid as screens are details and sections of images from the 1970s. Spread over twenty shifting screens Diggle sifts through layers that express a sense of inbetweenness (“halfway between tomorrow and yesterday” reads one text), dissolving together sheets of memory.

The central moving image work (the youtube clip) at first appears to be an abstract diagrammatic representation of the dimensional shifts of the Large Hadron Collider, through slowly shunting Mondrian-like vertical and horizontal lines. It’s like some odd Rorschach test machine squeezing fluid, fleshy muscular masses. On closer observation however it shows the artist’s mouth in slow motion throwing up coffee and spit, the fluid transferring from his mouth on one side of the graph through the air and back into his mouth on the other. The work rather neatly visually represents the movement and interaction of the corporeal and mechanical with physics that Diggle is exploring.

The text read on entering the exhibition is also used in the blog, and overlays the other images in the show. Yet from this I find it impossible to weave any kind of textual structure or narrative together. This is the work’s weakness, yet isn’t exactly surprising given Narvik’s Complaint is about working towards impossibilities and the inevitable failing of communication across time. There’s something of the adventurous and humourist spirit of our own Len Lye in this. The Film Archive blurb for Narvik’s Complaint speaks in Hollywood film synopsis language of a compelling narrative Diggle can never deliver on: “the artist travels through time and space to warn his 1976 self against potentially perilous life choices - but will young Jeremy listen? And should he?”

Diggle’s work is the antithesis of such straight-as-an-arrow storytelling. The work is principally an exploration of how far you can push the mechanics of storytelling over space and time rather than an exercise in good storytelling. And while some may feel with this work they’re being dragged back into postmodernism’s self-referential layering, it should be noted much self-portraiture of the last century have shattered clear narration and representational depiction in favor of existential fragmentation.

What is universal and ultimately moving about Narvik’s Complaint is its expression of how in our heads our past and present are in a state of constant collision. How, as we move forward we are also constantly looking back through a shattered prism of memories and scrappy recollections. We are as trapped by our past as we are empowered by it.

Images courtesy of the artist.

Recent Comments

Mark Amery

Blogger Mark said... Couldn't agree more Julie, but it remains of necessity a conundrum, and this doesn't make it any ...

Editor

Thanks Julie. So we are talking about turning weaknesses to strengths. I guess if Jeremy regards an 'inevitable failing of ...

Editor

John Hurrell said... Please give us your name, Da Vinci enthusiast.

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 3 comments.

Comment

Editor, 11:04 p.m. 5 March, 2010 #

John Hurrell said...

Please give us your name, Da Vinci enthusiast.

Editor, 12:07 p.m. 6 March, 2010 #

Thanks Julie. So we are talking about turning weaknesses to strengths. I guess if Jeremy regards an 'inevitable failing of communication' as inevitable - perhaps even for his show, desirable - then it is a strength.

Mark Amery, 3:10 p.m. 6 March, 2010 #

Blogger Mark said...

Couldn't agree more Julie, but it remains of necessity a conundrum, and this doesn't make it any less a weakness. Both a strength and weakness then! I often think great art pushes things close to the point of failure. Again how this journey is communicated is vital - the viewer must feel involved, as you do here.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.