John Hurrell – 16 July, 2010

These realistic drawings are based on sections of famous photos or images of marble sculpture, the very thin, impeccably controlled, paint appearing to have been caressed onto the outer weave of the fabric with a dry brush so that the calico's grainy texture is conspicuous. They appear to be halfway between the oil paintings of Fomison and the lighter, grainier charcoal drawings of Seurat - but with a curious flattening, an odd highly subtle compression of space.

This exhibition is an extension of aspects of John Ward Knox’s earlier Melville display of biro drawing and wall carving, mixed with his last Newcall installation preoccupied with light entering the gallery space. This show blends drawing with painting by making on stretchers of light calico, drawings with dark umber oil paint, paint used to depict shadow as a method of elucidating form. The thin material lets the light bounce of the walls behind the image, revealing the inner batons of the stretcher.

These realistic drawings (I call them that despite the above - because that is the image tradition they fit best into) are based on sections of famous photos or images of marble sculpture, the very thin, impeccably controlled, paint appearing to have been caressed onto the outer weave of the fabric with a dry brush so that the calico’s grainy texture is conspicuous. They appear to be half way between the oil paintings of Fomison and the lighter, grainier charcoal drawings of Seurat - but with a curious flattening, an odd highly subtle compression of space.

As with the best of the biro drawings, some works go beyond showing off a virtuoso technique to reveal very clever cropping and shrewd choice of source. Ward Knox tends to pick an image, ignore the main subject-matter and zero in on some peripheral detail that catches his eye. Often it is his method that does something curious spatially or psychologically to that carefully considered detail that alters its interpretation, generates a misreading within a new context, and so injects it with a completely different narrative life.

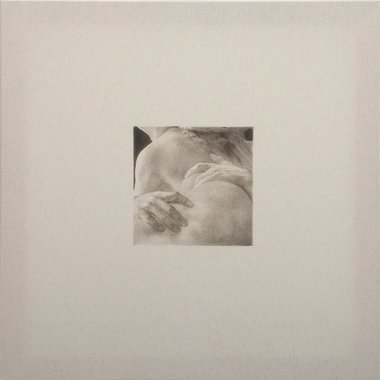

Take for example the work x (life, still, Hold). It is based on a photograph of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s virtuoso marble statue in the Vatican, The Rape of Proserpina (1622), showing Pluto kidnapping the fertility goddess, his gripping fingers digging tightly into the flesh of the small of her back and her outer thighs.

Ward Knox’s rendition is more mysteriously ambiguous, and in isolation before you chase up the source, appears at first glance to be showing Proserpina’s body so that her head is hanging down towards the viewer and that her feet are far away. The glimpse of her hanging ringlets of hair at the top could be part of a lacy undergarment.

What causes the ‘wrong’ understanding is that her grasped back above the buttock could be mistaken for a fondled breast. Of course once you see the source image then everything ‘correct’ is forever obvious, but until that occurs, the lack of information in the painting discourages that comprehension.

In x (life, still, Baby), his version of the bottom half of Julia Margaret Cameron’s 1865 photograph Prayer and Praise, the girl facing the camera above the head of the reclining baby being held by its mother has a slightly demonic look, a faint whisper of evil that chills due to the proximity of the sleeping infant. Probably - going on his recent NZ Herald interview where he talks of minute details on the face as ‘soul descriptors’ - the nuance is an accident (via translation) that Ward Knox is happy to leave. Something to make the image linger longer in the mind, a twist far removed from the devotional source material of a hundred and forty-five years ago.

In a piece of writing he provides with the show he talks about doing new verisons of old art and musicians singing new versions of old songs, and what the new versions add. Though he oddly claims to let the old material speak for itself, that is not strictly accurate. Ward Knox has deftly transformed it into a different sort of artwork of his own, something quite remarkable.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.