John Hurrell – 15 October, 2010

Some of the prints, especially those in the Playground Series, are too fingerwagging and histrionic, yet even within those, fascinatingly repugnant but mesmerising images turn up - such as Playground III, a symbolically societal Snakes and Ladders board with the career advancements and economic descents signified by centipedes and forms of marine plankton such as arrow worms. These wiggly creatures are quite disturbing but the work is still compelling viewing - it holds your attention despite its creepiness

Wellington

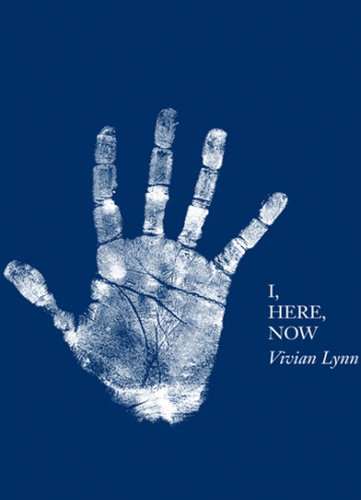

I, HERE, NOW, Vivian Lynn

Ed. Christina Barton

Contributions by Christina Barton, Anna Smith, Charlotte Huddleston, Ian Wedde, Anne Kirker, Pamela Gerrish Nunn, Guyon Neutze, Priscilla Pitts, Sarah Treadwell and Laura Preston.

128 pp, 27 colour plates

Published September 2010

This publication is the catalogue for the recent Vivian Lynn survey held at the Adam, a show partly augmented by some key Lynn works being simultaneously presented at Te Papa - in Charlotte Huddleston’s We are Unsuitable For Framing.

It is a fascinating book, with a lot of discussion crammed into its modest size, and sorely needed, but it is a shame it isn’t bigger simply so that the art images and biographical photographs could have their detail and narrative elements more widely appreciated.

Lynn (b.1931) is a highly complex, contradictory individual, promoted correctly as a forthright and articulate pioneer feminist with some important group exhibitions in her long career (such as Alter/Image [1993] and Anxious Images [1984]) but on other occasions often springing away from such labels like a scalded cat. Sometimes she sets out to deliberately scorn notions of aesthetic beauty in her content-driven drawings and sculpture, other times she embraces them. On some occasions she focusses on the community around her, on others she openly flaunts her own ego and stridently celebrates her individuality.

The catalogue is roughly divided into three sections. First there are two long superb essays on Lynn’s life and work by Christina Barton and Anna Smith that offer insights into the various gender-based political issues that for over fifty years have driven her art practice. Then there is a suite of eight short articles on key projects by various authors examining the qualities that Lynn is known for in her often acerbic prints, paintings and installations. And finally there is a remarkable chronology by Laura Preston and Barton that sets Lynn firmly into the historical context of various urban and rural communities in Wellington and South Canterbury, and her life as a farmer’s wife, mother, teacher and social commentator. These three areas work well together, cross-fertilising and rewarding any endeavours by an enquiring reader wishing to dig out thematic threads within each.

Lynn’s best work - like Mantle, restoration piece (1982 - 2008) for example - is designed to disgust and then win you over. Repellent piles of clipped women’s hair have overtones of Nazi camps, hidden bloodsucking insect life and repressed sexuality, but it makes you shudder and keep looking (for the varied hair types make it perversely beautiful). Sculptures like G(u)ardian Gates (1982), Stain (1984) and Self Portrait (1981) intrigue because of the male/societal symbolism of the industrial products used (like plastic piping or wire netting) as devices of behavioural control or metal pinioning.

Some of the prints, especially those in the Playground Series, are too fingerwagging and histrionic, yet even within those, fascinatingly repugnant but mesmerising images turn up - such as Playground III, a symbolically societal Snakes and Ladders board with the career advancements and economic descents signified by centipedes and forms of marine plankton such as arrow worms. These wiggly creatures are quite disturbing but the work is still compelling viewing - it holds your attention despite its creepiness.

Lynn’s work in fact contains a loaded ambiguity, an oscillation where although images are often crammed with didactic gender-political references, they still operate on a bodily level. Because I personally believe the best art is dead simple, not complex - that a focussed ‘theatrical’ gesture can result in many radiating semantic resonances - Lynn’s important work doesn’t always need those resonances spelt out literally in titles, essays or their footnotes. (I think the same about Len Lye and his ideational content.) But as art now supports a major industry in cultural interpretation, of which sites like the one you are now reading (and this catalogue too) play a part - it is understandable that things often get overstated, but with obvious community benefits. Lynn deserves to be far more widely known than she is. This book of images that are potent and penetrating (those are the right words) and feminist history should be in every town library.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.