Andrew Paul Wood – 7 August, 2012

The surety of composition and technique owe as much to the rigid technical training Zhonghao received in China prior to coming to New Zealand as much as it does to Ilam's preservationist but not heavily enforced approach to teaching painting, sculpture, photography, film and printmaking. Largely based in China now, his work may now lie in an uneasy relationship with the conservative mainland Chinese art market and its preference for polite figuration.

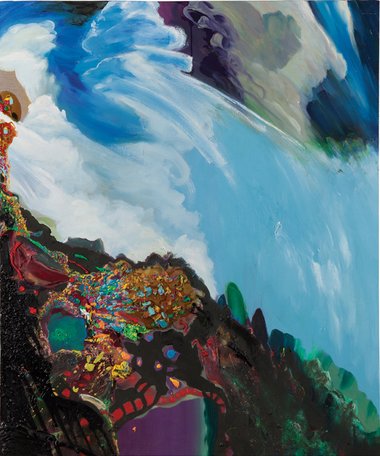

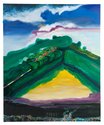

Zhonghao Chen is a graduate of the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts. This latest exhibition of his work, at the Jonathan Smart Gallery, reveals considerable evolution over the last couple of years from the works that might be described as Soutine in Chinatown - chicken carcasses rendered in a darkly lurid palette and thickly, viscerally applied paint. These works are much lighter, sharper and purer of hue. The thickly clotted paint has parted like the Red Sea before Moses, retreating to the edges like a frame to reveal big vertiginous skies, mysterious picturesque light, and surreal fantasy landscapes touching on a number of tropes including Pop slickness, late Victorian Romantic sublimity, the quasi-abstract Canterbury landscapes of Bill Sutton, the classical landscape traditions of Chinese painting, and perhaps even science fiction cover art. In Chinese tradition, painting is a philosophical vehicle, not simply an experience for the eye.

Through the thick expressionistic and viscerally gestural paint we see a hint of an idyll. The famous Chinese fable The Tale of the Peach Blossom Spring, written by Tao Yuanming in AD 421 tells the story of a fisherman accidentally sailing his boat down a strange river in a forest of blossoming peach trees, eventually arriving in a paradisiacal village which he was never able to find again. The expression shìwaì taóyuán “the Peach Spring beyond this world” is a popular Chinese metaphor for a beautiful place not easily visited. The magical landscapes we can see beyond the abstract barriers hints at such a locus amoenus, recalling the love grottos of Rococo art. In Taoist art we also find the Dòngtian or grotto-heavens of caves and mountain hollows, and perhaps all of these are touchstones in ZhangHao’s paintings.

Zhonghao came from an artistic, musical family, and drew from a young age. He studied in a special high school attached to the Nanjing University of the Arts, the oldest academy of the arts in the People’s Republic of China, before moving to Auckland in 2003 to take seventh form at the International College. The Chinese training was heavily influenced by Socialist Realism and provided the meticulous attention to accuracy and detail in Zhonghao’s draughtsmanship, but much of the conceptual and art historical context came from his training at Ilam (BFA hons 2007, MFA 2010), but also informed by a passionate love of Bacon, Freud, Soutine and other expressionists. However, just as with the Taoist and Confucianist inspired Literati paintings of fifteenth and sixteenth century China, the human element is marginal, and dramatically reduced to a meltingly surreal building or other technicolour artefact, so as not to distract from the underlying cosmic unity.

In some ways this exhibition is Orientalism in reverse - Occidentalism: more an ironic and self-conscious metronoming interplay between half-serious Eastern and Western perspectives, between abstraction and the figurative, between surface and texture, rather than a true synthesis. It’s wide ranging, but logical and balanced, never chaotic. The painterly abstraction in its candy-colours shares space with recognisable dramatic rocky mountains from Shan shui brush painting and sometimes cartoonish figures more suggestive of China’s commercial present. These brightly-coloured entities, called “muppets” after Jim Henson’s creations in the work title, are the “klaxons” of the exhibition title - but what are they announcing? The change in aesthetic direction, perhaps?

The surety of composition and technique owe as much to the rigid technical training Zhonghao received in China prior to coming to New Zealand as much as it does to Ilam’s preservationist but not heavily enforced approach to teaching painting, sculpture, photography and film, and printmaking. Largely based in China now, his work may now lie in an uneasy relationship with the conservative mainland Chinese art market and its preference for polite figuration, so it would be interesting to know how the paintings are received back in PRC. From my conversations with the artist, the Chinese collectors respond more favourably to the paintings with the stronger traditional figurative elements.

It helps underscore the absurdity of New Zealand dealers trying to break into the holy grail of the Chinese art market because tastes are not universal, and China has more than enough artists of its own to fuel the local market. If anything the flow will be in the reverse direction as China becomes increasingly influential in global culture. Nor does China require patronising by external art critics of the west when it boasts such perceptive commentators as Wang Gungwu, Huang Zhuan and Gao Mingiu, and curators like Zu Huan, Wu Meichun and Huang Du. What New Zealand may usefully provide is advanced fine arts training to emerging artists.

Andrew Paul Wood

Recent Comments

Andrew Paul Wood

Or perhaps anthropological alarm horns

Andrew Paul Wood

Basically the totemic muppet creatures that appear in some of the paintings are bright, loud and have wide open orifices ...

John Hurrell

A klaxon is a car horn, right - Andrew? So when you connect it with muppets I'm a little confused....

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 3 comments.

Comment

John Hurrell, 9:40 a.m. 7 August, 2012 #

A klaxon is a car horn, right - Andrew? So when you connect it with muppets I'm a little confused....

Andrew Paul Wood, 9:46 a.m. 7 August, 2012 #

Basically the totemic muppet creatures that appear in some of the paintings are bright, loud and have wide open orifices that would seem to be there to produce sound. Admittedly it is a little hard to explain.

Andrew Paul Wood, 9:49 a.m. 7 August, 2012 #

Or perhaps anthropological alarm horns

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.