John Hurrell – 12 July, 2013

What is impressive about 'Nobody But You' is its examination of material that is extremely public but rarely analysed, and pertaining to creative individuals focussing on personal relationships. Those Duchampian doorways that suggest a look into these musicians' ‘souls' make a crafty and refreshing component, encouraging you to speculate about the trivial motivations that really propel most art production.

Musician and artist Torben Tilly presents an intriguing installation at Audio Foundation, one that incorporates two rooms (one light, the other dark) in a way that cohesively exploits the connecting doorway in between.

His show looks at the well known rift between the founding members of the legendary rock group, The Velvet Underground, Lou Reed and John Cale - at the end of the sixties after their second album White Light White Heat - cognisant of the fact that years later they made up to record the Warhol tribute, Songs for Drella. Tilly ties in his ideas about this celebrity spat with various references to a Duchamp work, Door, 11 rue Larrey (1927), punning on the notion of a double portal that peers from public into private: two doors (Coeval) and separated double linkedway (Taking Sides) that allude to two album sleeves that contain elements of a then ongoing quarrel. And a sound element that references time going backwards, plus a print that makes an acerbic aside on rock history.

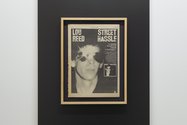

Like most of us, Tilly is obviously fascinated when he sees adults (even his heroes - especially his heroes) behave like petulant children. And looking at the way he has positioned his two unattached black doors, one upright bearing a framed New Musical Express ad from 1978 promoting Street Hassle, the other inverted presenting another New Musical Express page - from 1975 - advertising three John Cale albums - including the then most recent Slow Dazzle.

So considering the similarly titled names, and images of both artists looking butch and wearing aviator sunglasses that sparkle, I here have a theory of my own. Both Reed and Cale quite justifiably have literary aspirations, and on White Light White Heat, the album which drove Reed into sacking Cale, there is one track, The Gift, a piece of prose written by Reed but recited by Cale, that Reed was obviously very proud of. But six years later on Slow Dazzle, we see Cale present another piece of prose, one clearly much better: The Jeweller. So then an irritated Reed retaliates and three years later still, has an even more brilliant piece of writing, the stunning Street Hassle that includes a wonderful verbal performance by Bruce Springsteen, helping it reach a massive audience Cale would never achieve.

The above details are my guesswork, though I think for anybody interested in rock of the seventies it’s pretty obvious. Getting back to Tilly and his presentation with the two very differently lit (and differently aural) rooms, the bright one has a single cymbal (a pun on symbol) that is hit by a lever so that the crashing noise is transmitted to a receiving radio (Specious Presence), but broadcast backwards. It creates a subtly swelling, very discreet vibrating sound. Tilly is contemplating the act of looking back in time and the extra hindsight about events we often have now when considering petty behaviour (our own or someone else’s).

The dark silent room mixes the taunting significance of Cale/Reed’s sunglasses - projected for 3 secs every half minute, a film loop (Slow Dazzle) cleverly made by Tilly using purchased sunglasses that are identical - with (on a far wall) a very dark risograph print that states: if there is a perfect rock ‘n’ roll past, this is it.

That caption is pretty funny because it suggests bitchy behaviour is what people remember, and what people remember makes up this thing called ‘history’. Sinners, not saints, are what matters.

All up Tilly is obviously at heart a moralist, not a flippant cynic, nor one overtly reprimanding or judgemental - after all it is the Cale image he inverts, not Reed’s - and Reed seems the pettier of the two. Yet that view is slightly over-reacting because Reed with his Street Hassle cover is just needling Cale. It is not super nasty. More a silly little joke that will play on Cale’s paranoia.

What is impressive about Nobody But You is its examination of material that is extremely public (and much loved) but rarely analysed, and pertaining to creative individuals - not governments or boards of directors - focussing on personal relationships. Those Duchampian doorways that suggest a look into these musicians’ ‘souls’ make a crafty and refreshing component, encouraging you to speculate about the trivia (not noble cultural aspirations) that really propels most art production.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.