Andrew Paul Wood – 15 March, 2014

It is probably true to say that Hunter's floreat was the 1970s, but a revival of interest in early feminist art led in 2007 to a solo show, 'Alexis Hunter: Feminism in the 1970s' at Norwich Gallery at Norwich University of the Arts in the UK and at Whitespace in Auckland. Reviewing it in Frieze, Kathy Battista described it as situating Hunter's practice, “as an important contribution to Britain's feminist movement within the visual arts”.

EyeContact Obituary

On the 24th of February this year, pioneering feminist artist Alexis Hunter finally lost her battle with motor neurone disease. Living in London since 1972, Hunter was born in the Auckland suburb of Epsom in 1948 to parents who had emigrated from Sydney the year before. Raised in Titirangi, from 1966 to 1969 she and her twin sister Alyson studied at Elam where, tutored by Colin McCahon, she found lasting inspiration in his ethos that the artist has a responsibility as a member of society. News of the Paris riots motivated Hunter to hitchhike around Australia with future film producer Janine Dickins, living for a while in a commune in Cairns.

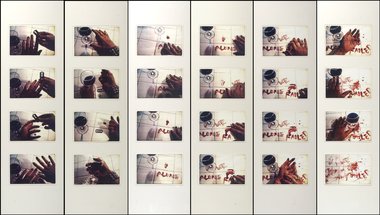

Upon moving to London, Hunter worked in film animation, working on movies like Star Wars and Alien (and in 1986 The Little Mermaid) and became a member of the Women’s Workshop of the Artists Union, an organisation which existed from 1972 until 1975 and which was much maligned by a patriarchal press. Being uncompromising in her art led to confrontations: photo labs refused to print work like Sexual Warfare (1975) a grid of photographs with text where her own hands demonstrate various methods of murdering a male partner, including castration with a pair of scissors. Hands feature prominently in other works as well, such as Approach to Fear II: Change-Decisive Action (1977) in which red nail polish is removed and manicured nails cut short with a razorblade.

Despite the affected working class British accent she adopted, Hunter retained a close connection to her New Zealand identity. Her photography of European tattoos came about from her anger at hearing tattoos being treated in an offhand manner in a lecture at the Royal Academy and her knowledge of their significance in Maori culture. Hunter also liked to mix humour with her social message, as in The Marxist Housewife (Still Does the Housework) (1978) depicting another manicured hand washing a poster of Karl Marx in reference to both class issues and the philosophers ignoring of domestic labour in his writings. Hunter‘s photography turned the tables on the cliché of the male gaze. Her voyeuristic Sexual Rapport works (1972-1976) taken in Hoxton, London and Little Italy, New York, made the male the object - workmen, policemen - rated “Yes”, “No”, or “Maybe” depending on how sexually attractive she found them.

Her 1978 solo exhibition Approaches to Fear was shown at London’s ICA. Her work also appeared in the Hayward Annual that year, causing a furore in the British art press. The Guardian called it “disgusting” and the Hayward was, for a time, nicknamed “the Wayward. It was mainly the nudity which offended delicate sensibilities as in Approach to Fear: Masculinity - Exorcise (1977), in which Hunter’s polished fingernails smear viscous black ink across the genitalia on an image of a beefcake model, but the work also earned her the scorn of some radical feminists who felt the populist, hypersexualised and slickly glamorous aesthetic of her work was counterfeminist and dangerous. This photographic work, however fits comfortably alongside the work of Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, and Cindy Sherman. They also share a certain resonance with the fetish photography of Robert Maplethorpe. The work she was most proud of was Dialogue with a Rapist (1978), a series of multiple exposures of a street scene with snapshots of a knife and a woman’s hand around a man’s throat, accompanied by a handwritten description of Hunter’s exchange with a man who attacked her on a Bermondsey street.

Hunter showed at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in 1979, and at the Serpentine Gallery, London in 1981, the Sydney Biennale in 1982, the Totah Gallery, New York in 1984, and the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1987. That year she served as associate Professor of Painting and Photography at the University of Houston in Texas. Her work was also included in the touring exhibition Fantasy in 1994, no less ironic for one of the destinations being the United Arab Emirates. To the end, Hunter had an ambivalent attitude to Islam and was a very open critic of the treatment of Muslim women. It would be trite to suggest this as merely typical British Islamophobia, for Hunter had seen it first hand as a lecturer at the American School, Women’s Technological College, the Cultural Centre and the Women’s College of Technology in Sharjar, Ras Al Khaimah.

Sometime in the early 2000s Hunter joined the Stuckists. Stuckism was an international, but extremely British, art movement founded by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson in 2000 to promote figurative painting, a reaction against the meteoric rise of the YBAs. The name was coined by Thomson in 1999 in response to a poem by Childish about the latter’s former girlfriend Tracey Emin describing him as “Stuck! Stuck! Stuck!” in his art. Hunter’s contribution to Stuckism was a fusion of Symbolist atmosphere and Neo-Expressionist gesture that increasingly came to rely on ironically imitating the individual styles of canonical male painters.

It is probably true to say that Hunter’s floreat was the 1970s, but a revival of interest in early feminist art led in 2007 to a solo show, Alexis Hunter: Feminism in the 1970s at Norwich Gallery at Norwich University of the Arts in the UK and at Whitespace in Auckland. Reviewing it in Frieze, Kathy Battista described it as situating Hunter’s practice, “as an important contribution to Britain’s feminist movement within the visual arts”. Never shy of a controversy, Hunter used for the cover of the exhibition catalogue an image from Sexual Rapport depicting a man’s bare torso, wearing leather trousers, holding a cigarette at the level of his crotch, posed against the twin towers of the World Trade Centre as the “ultimate phallic symbols” - something of course, which takes on many new meanings post 9/11. This revival also saw her work included in the 2007 exhibition Wack! Art and the Feminist Revolution at MoCA in Los Angeles. At the same time she was included in the Stuckist show I Won’t Have Sex with You as Long as We’re Married at the A Gallery in London. In 2008 she founded the Camden Stuckist group in London.

Hunter continued to travel back to New Zealand until her motor neurone disease made this impossible. The cruel condition eventually left her only able to communicate through a tablet. She is survived by her twin sister, printmaker and photographer Alyson Hunter, sister Linley Hunter Torres, and husband ex-Saracens rugby International and one time owner of The Falcon pub, Baxter Mitchell. Hunter’s cause remained her chief passion to the end, saying in an interview shortly before her death, “The word ‘feminist’ to me conjures up a world of travel, experiment, intelligent people and bonding for a common cause.” She elaborates, “The only way of keeping this alive is by supplanting the word with a new voice of vibrant new feminists utilising Facebook and net petitions. This third-wave feminism has all the frontiership of the radical feminists of the 1970s.” She was 66.

Andrew Paul Wood

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Here are some terrific comments about Alexis Hunter from Ron Brownson. http://aucklandartgallery.blogspot.co.nz/2014/03/remembering-alexis-hunter.html

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 1:58 p.m. 21 March, 2014 #

Here are some terrific comments about Alexis Hunter from Ron Brownson.

http://aucklandartgallery.blogspot.co.nz/2014/03/remembering-alexis-hunter.html

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.