Andrew Paul Wood – 22 February, 2015

One of the things immediately noticeable is that the work has clearly been selected by Theodore on artistic merit rather than, as many western institutions might have done, for exotic colour. This tends to highlight how uniform and globalised the processes and aesthetic of contemporary art has become among the international upper middle class who can afford to study it, but also allows the artists to stand out as individuals rather than merely ambassadors of their home culture.

Christchurch

Group show

The Network: Contemporary Art from India

Curated by Sanjay Theodore

13 February - 7 March 2015

Christchurch, it has to be said, has a certain (if unfair) reputation as the whitest city in New Zealand, but in fact there has been a resident Indian population since its early days. The hill suburb of Cashmere was not only named for the problematic region of Kashmir, but was coincidentally also home to one of the first communities of Indians in New Zealand who largely arrived in in 1859 as servants for John Cracroft Wilson, who, prior to transferring to New Zealand, had been a magistrate in India. There are echoes in the local street names: Shalamar Drive, Bengal Drive, Darjeeling Place, Delhi Place, Indira Lane, Lucknow Place, Nabob Lane, Nehru Place, and Sasaram Lane. It is always nice to see the connection between the two former pink-coloured bits of the map revived now that the imperial centres of influence have swapped around somewhat.

In April 2014 the Jonathan Smart Gallery in Christchurch sent an exhibition of contemporary New Zealand work curated by New Zealand-Indian artist Sanjay Theodore to be exhibited at the Chatterjee and Lal Gallery in Mumbai, India. This was the first half of The Network, a reciprocal exhibition and cultural exchange, which comes full circle with an exhibition of contemporary Indian art at the Jonathan Smart Gallery. Such exchanges, while common enough between public institutions, are unusual between unaffiliated dealer galleries. The artists represented are some of the top names in contemporary Indian art. The Physics Room exhibition of Mercedes Vicente‘s Art and Social Change Research Project: Delhi Residency, 2013 in 2014 offered a useful primer in understanding some of the many complexities of being a contemporary artist in India today.

One of the things immediately noticeable is that the work has clearly been selected by Theodore on artistic merit rather than, as many western institutions might have done, for exotic colour. This tends to highlight how uniform and globalised the processes and aesthetic of contemporary art has become among the international upper middle class who can afford to study it, but also allows the artists to stand out as individuals rather than merely ambassadors of their home culture. The work in the show is mostly originally performance based; records of work often put on in North America or Europe. Sahej Rahal‘s shamanic Bhramana II (2012) is surely influenced by Joseph Beuys’ 1974 I Like America and America Likes Me, and Rana Dasgupta’s Vox in Camera (2001-13) ultimately owes much in concept to Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973-79). There is, however, sufficient sense of place to stop it all tipping over into the bland abyss of le menu touristique. At the same time this is also a self-conscious artefact of India’s complex love/hate relationship with the inheritance of the British Empire and the west in general; something these artists are also exploring in their work.

Nijinsky used to say that the secret of his dancing was that he leapt, and “paused”. Kiran Subbaiah‘s video stills Flight Rehersals (2003) cultivates a similar sensibility - the boy who could fly - which is as much suggestive of the levitating fakir as it is of Peter Pan as through camera trickery the artist appears to hover in the midst of mundane life. Gagan Singh‘s perky little cartoonish ink drawings reminiscent of the naughtier kind of Indo-Persian miniature blend the imagery of Ramayana and Mahabharata by way of the Kamasutra and the temple carvings of Khajuraho, with a most un-Sikh-like, wittily pornographic perversity that is entirely the artist’s own. Hetain Patel‘s The First Dance (2012) is a very sweet video work interweaving the artist’s boyhood kung-fu movie fantasies growing up in the UK with the paradoxical everyday exoticism of a British Hindu wedding ceremony.

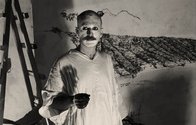

Minam Apang’s drawing from the Moon, River, Mountain series (2013) is lush in charcoal and tea wash on cloth, simultaneously both delicate and spry, combining a training in Buddhist thangka scroll calligraphy with the rich feast of Indian mythopoesis, though this is a tranquil example where the figurative elements seem almost chastely abstract. Nikhil Chopra‘s photographs and souvenir smock from his 2013 Blackening V performance also has a visually striking, strongly Beuysian sensibility, but for me it seemed to lose too much divorced from the performative context that artefacts alone did not quite convey.

For me, I think, the stand out work of the show is Theodore’s himself, simply because it brings together so many threads of human narrative and modern India. It consists of a blue tarpaulin crudely fashioned into a sort of tent, and a travelling trunk. It’s considerably more restrained and subtle than Theordore’s other sprawling installations. The trunk contains a couple of possessions and a number of framed photographs of a young man whose lower face has been horribly disfigured into a Gwynplaine-like grimace. The young man, known to Theodore, was one of the millions of modern India’s legion of the precariat, a worker on one of the countless construction sites in the building boom of India’s teeming cities. He fell, injuring his face, which doctors managed to partially reconstruct. The pay-out from his employers, while not very much by western standards, allowed him to go from the improvised tent and travelling case which were the entirety of his possessions, and return to his village as a man of relative means. The title of the work, The Temple of Apollo (2015), plays on the famous exaggerated smile of Archaic kouroi, the inversion of the cult of youthful male beauty, and the installation as a kind of votive shrine. For the young man, perversely, it is a happy ending.

It’s a shame the show is only up for three weeks.

Andrew Paul Wood

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.