Nicholas Haig – 20 October, 2016

Salmon's practice is didactic - absolutely. But it is also as much about formulating an ethics of practice as it is ‘conveying a message'. Furthermore, I am quite sure that Salmon understands that the weight of the issue of climate change can in no way either be adequately represented or captured by the work. Which means, with regard to Salmon's practice and her ethics, that disappointment is fundamental. The didacticism is, at least in part, forlornly ironic.

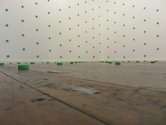

Hundreds of green plastic trim-milk bottle-tops arrayed in neat formation on three walls, the floor, the ceiling. Four A4 colour printouts Blu-Tacked to the wall: two from what I assume was a governmental report on agriculture and climate change and two outlining Fonterra’s sustainability policy. Next to them, a woozy, murky, ill-looking painting of a milk jug. And then, a quarter of a breadboard painted white and pinned in a corner at skirting height.

Catharine Salmon has in recent years frequently played such a hand: pleasurable visual riddling colliding with a ‘plain-spoken’ didactism of the ecological kind. For instance, Nature Morte: Milk Jug and Waterfowl (2013) coalesced spare precision with numinous aesthetics: a dance of eight splayed black and blue pūkeko wings; a thin green line of plastic trim-milk lids trailing off into a wall; a cheap porcelain milk jug (stolen from a tearoom?) stuffed with pūkeko legs resting on a half-round bread-board plinth painted white; and, easily overlooked (intended to be overlooked?), a quarter of a bread-board tacked into a corner just above the skirting.

Nature Morte whispered in a weird elegiac language and was fugue like - signalling abandonment and panicked, hysterical flight. I thought of it as having some loose kinship with Elizabeth Bishop’s poem The Moose. That is, meanderingly ominous and almost funny. In Bishop’s poem, the bus passengers’ chatter is silenced by the unexpected ‘advent of the beast’. With Nature Morte, one beast - the viewer, the witness - was silenced, was stilled, by the departure of another. But then again, there was an ambiguity to it because the bits of pūkeko did not lie supine on the floor but were found in antic and capering flight. A tragicomic exit-resurrection.

With Bubble, the disjunctive mood and mode is even more pronounced. It has become stickier, stranger, more perplexing. Its registers are at times delicate and at others heavy-handed and passive-aggressive; an optic lullaby meets martial bugling; shit-stains meet the freshly laundered. By which I mean, it could be innocently perceived as celebratory of New Zealand’s agrarian fecundity. And, given the lack of supporting documentation, the inclusion of the ‘Sustainability Fact-Sheet’ could lead one to believe that the exhibition was a strange work of Fonterra PR.

Of course, ‘green-wash’ is exactly what Salmon is getting at, but Bubble cannot be read as whole-heartedly parodic in a mimetic sense given the nastiness of the painting. The jug, as a symbol of plenitude, nods in the direction of McCahon’s The Virgin and child compared (‘The Blessed Virgin Compared to a jug of pure water and the infant Jesus to a lamp’), though here the fluid is filthy, the milk surely sour, the ‘green-house gas’ ejaculation (something is ‘spilling’ skyward) cataclysmic. Fonterra’s corporate slogan is ‘Dairy for life’, and it took some time for me to understand it in this context as an admission of guilt over the exchange required: dairy for life.

Perhaps the Fonterra documents, with their casual and crooked presentation, were included out of a sense of exasperation? In the sense of the persuasiveness (because endlessly repeated) of Fonterra’s eco-friendly rhetoric: we really do care and we really are doing something. The blunt irony of Bubble, with the documents displayed on the wall adjacent to the effluent painting, risks, as a friend put it, a ‘double disaffection’. In other words, the failure of the painting meeting the obvious and inevitable failure of the sustainability model leaves the viewer/reader with nowhere to go. Governmental and corporate dysfunction mimed by painterly dysfunction. An impasse.

Peter Dornauf, in his recent EyeContact review of the National Contemporary Art Award 2016, stated: ‘Climate change like the problem of homelessness are serious and urgent contemporary concerns, but if I want propaganda, I’ll look for it at some politically rally. Art, of course, can be didactic, but do I want to be hit over the head with a hammer?’

Salmon’s practice is didactic - absolutely. But, as I understand it, it is also as much about formulating an ethics of practice as it is ‘conveying a message’. Furthermore, I am quite sure that Salmon understands that the weight of the issue - in this instance the crisis of climate change - can in no way either be adequately represented or captured by the work. An element of failure is inevitable, is ‘structuring’. Which means, with regard to Salmon’s practice and her ethics, that disappointment is fundamental. The didacticism is, at least in part, forlornly ironic.

Returning to the bottle-tops, every now and then the regimented spread of this ‘ambient landscape’ is disrupted: a darker top here, a hiccup in the pattern there. These aberrations could easily be missed. When seen obliquely, pink dots appear and when looked at from along the wall, the circular tops begin morphing into squares. The suggestion being, the entreaty being, to have - and to make - a perspectival shift. What to do when I know that a part of me revels in the crisis and takes perverse pleasure from knowing full well and doing nothing? Of finding in the crisis of climate change an opportunity to submit to exhaustion.

What, then, should I make of this (purposefully?) mangled dialectic? No negation of negation, but simply, negation? Its various ‘redundancies’ piling on top of one another to form a despairing indictment? To flesh this out a little, the green-tops are a pleasurable comment on green-wash. The pleasure is and as the green-wash. I know this is so but what, when I leave, do I take with me? The pleasure of the optical seduction or the sense of an urgent need for political action? Could it be, therefore, that my discounting of the efficacy of Salmon’s ethical positioning - her plea for action - is precisely the point?

The bubble of the title, Salmon suggested in an article in the Nelson Mail, was to do with atmospheres and atmospherics, insularity and ignorance. Perhaps Bubble should thus be perceived, and a little like the box holding Schrödinger’s cat, as both prison and paradise. Within it we are dead and alive, always, already.

And what of the breadboard? Judith Butler adds another dimension to this:

If the humanities has a future as cultural criticism, and cultural criticism has a task at present, it is no doubt to return us to the human where we do not expect to find it, in its frailty and at the limits of its capacity to make sense. We would have to interrogate the emergence and the vanishing of the human at the limits of what we can know, what we can hear, what we can see, what we can sense. (1)

The breadboard, for me, was where all sense of knowing or needing to know ran out. A pressured relief.

Nick Haig

(1) Butler, Judith. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004), 151.

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.