John Hurrell – 5 April, 2017

Obviously you can enjoy these works without taking too obsessive an interest in how they were made. You might not be disposed towards puzzle solving and the mysteries of threading technique (or its coloration), but you can relish instead decorative rhythms discoverable on enigmatic ornamental objects projecting out from these walls.

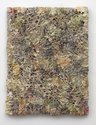

Richard Bryant’s six, very unusual, paintings that we see presented on the walls of the Ivan Anthony gallery, are made not with the expected painted canvas stretched taut on stretchers, but with woven and jammed fragments of stained fabric mingled with softly coloured string, thread and twine. This has been repeatedly and intricately stitched around and across frames to look cumulatively like flaxen chair seats, worn down doormats, squares of dug-up turf, or (perhaps) giant kataifi Greek pastries. Overall, the compressed forms look vaguely baked, like decorated (but squashed) loaves of bread or freakishly enlarged crunchy biscuits.

The process of making these coarse, fibrous ‘textile’ objects seems complex, for the colour application varies between the staining of the outer spongy surface, dry brushing the taut lines, the colouring of the thread in isolation before sewing, or stitching in coloured cotton straight off the reel.

These Weetbix-like paintings are like tightened bundles or aggregate parcels wrapped in string, their enclosing web or network of skeins accentuated with colour. Some are daubed with dots or mottled stains, and others have a sense of washed on stains later being removed. The works invite you to ponder over the sequencing of their construction, seeking clues over pattern formation and the incorporation of fragments of fabric.

In a sense they might be seen as a kind of metaphor for the process of painting’s mental and physical construction, disparate elements from various cultural sources pulled together and now ‘unnaturally’ juxtaposed in a new context. You can ‘sit’ in them like Matisse’s armchairs for tired businessmen, letting your mind and eyes drift, and relaxing, or you can ravenously optically devour the individual linear or textural ingredients, speculating on the reasons for their inclusion, and consuming their formal elements rapidly.

These frameless grid paintings (for grid paintings are what they are, but organic and irregular in their linear crisscrossing, and not a hard edged geometric form to be seen anywhere) also change according to your distance from them. Their unpredictably bulbous (and lumpy) edges tend to flatten out when you stand back, so that the asymmetric undulating borders tighten. Also within each centre, paler linear configurations dissolve and darker configurations become more assertive. The marks change in accentuation and dominance.

If you carefully compare the paintings you will notice there are three distinct types: (1) wrap-around frames with stretched over webs (Beak and Thaw) with a definite compositional centre distinct from the framing border; (2) mottled rhythmic patches in a patterned holistic field (Vessel and Collar); and (3) tonally accentuated webs of linked-up lines (Flock and Comb) with stalks, stems and petioles.

With the saturated colours and textures that are akin to straw or shredded paper, you get associations of fabric patterns being mingled with the cereal tactilities of baking, while also visually hinting at fishermen’s nets laden with entangled seaweed and polluting paper or plastic. They are startlingly rich in associations.

Obviously you can enjoy these works without taking too obsessive an interest in how they were made. You might not be disposed towards puzzle solving and the mysteries of threading technique (or its coloration), but you can relish instead decorative rhythms discoverable on enigmatic ornamental objects projecting out from these walls.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.