Andrew Paul Wood – 5 September, 2017

The paintings in Christchurch in 'Homonoia People' seem almost austere and nearly monochromatic. The first impression is of a compositional grid derived from siapo (Samoan tapa cloth) the way that John Pule did with hiapo (Niuean tapa) in the early 2000s), but Leleisi'uao seamlessly merges this with the hieratic friezes of ancient Egypt, ancient rock art, the frames of the comic strip, Greek black figure vases, and possibly even Colin McCahon's 'Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury' (1950).

Andy Leleisi’uao has just won the Wallace Arts Trust Paramount Award. It was announced last night in Auckland at the Pah Homestead and he just happens to be exhibiting in Christchurch. Leleisi’uao was born in New Zealand in 1969 and grew up in Mangere, South Auckland. He coined the term “Kamoan”, “Kiwi-Samona”, to describe himself and other Samoan New Zealanders who exist in the Va (the space) between the two identities while not quite fully identifying with either. It is the questioning around this hybridity that fuels much of his imagery across a wide range of media.

In that regard, he legitimately sits within the flowering of Pasifika and PI-heritage artists in New Zealand that began with Fatu Feu’u and Michael Tuffery in the 1980s, and occupies the wave alluded to in Karen Stevenson’s The Frangipani Is Dead: Contemporary Pacific Art in New Zealand, 1985-2000 (Huia 2008) that moved away from self-conscious Pacific tropes and imagery, that had found favour with Palangi collectors (superficially read by the art market as exotic without the politics), toward more blatant searching, critical themes, and the finding of a voice.

Compared with the riotous palette of the 2015 Quaint People of Nuanua works, the paintings in Christchurch in Homonoia People seem almost austere and nearly monochromatic. The first impression is of a compositional grid derived from siapo (Samoan tapa cloth) the way that John Pule did with hiapo (Niuean tapa) in the early 2000s (the jellyfish forms in the paintings remind me a little of Pule’s clouds as well), but Leleisi’uao seamlessly merges this with the hieratic friezes of ancient Egypt, ancient rock art, the frames of the comic strip, Greek black figure vases, and possibily even Colin McCahon’s Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury (1950).

This scaffolding allows him to roll out his cavalcade of characters and personalised mythopoesis in a way that hints at both narratives and a syntax that is just out of reach for those without a fluent grounding in Fa’a Sāmoa (which obviously I don’t have). Where past, present and future exist simultaneously in an oceanic Pacific dreamtime.

It is the visual equivalent to the philosopher Richard Rorty’s “ironic pragmatism” - the Truth, or whether there even is a Truth, doesn’t matter because the interesting thing are the strategies people approach to get there. The enigma itself is the message, unless you are privileged enough to be initiated.

At the same time there’s a paradox because Leleisi’uao wants everyone on the same page. He wants us to see the situation through his eyes and is trying to create a new vocabulary in order to generously convey that precious information, but finds himself butting up against the Wittgensteinian dilemma of the contingency of the sign and language. The attempt to negotiate that dilemma is where the art is. Wittgenstein’s solution was aphoristic: “Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must remain silent,” which seems to me entirely antithetical to the purpose of art, which is why Leleisi’uao persists in trying to knock it down. He (and the viewer) are searching for that ultimate answer, but we struggle to explain to each other what the question is.

It’s probably helpful to think of something like Deleuzian Immanence—a plain of existence that includes everything simultaneously, even its own negation, because it has no outside—but the truth is that there is no concept in postmodern critical theory that wasn’t already anticipated in traditional indigenous worldviews millennia ago.

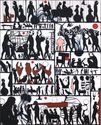

That enigma emerges in Leleisi’uao’s iconography of surreal creatures, Rubik’s cubes, crossword puzzles and jigsaw pieces; metaphors for the enigma of identity, although he also at times draws on social issues and human relationships as seen from the Va. There are the figures present only as dotted lines as though they have been subtracted or excluded. There is a lightness too, but it is a knowing and uncompromising lightness that acknowledges its inverse is the pain of oppression, brutalisation and racism. The ancient gods of the Pacific are also present in looming forms that seem part Rapa Nui (Easter Island) moai and part biomorphic Henry Moore sculpture. There are also Marshallese stick charts—the incredibly complex sculptural maps used to navigate the ocean currents of the Pacific—and mummy-like ancestral figures, whose pupae/rebirth significance may be alluded to by the presence of Monarch butterflies and caterpillars.

There are hints as well of ordinary, familiar human interactions: a cautious interplay between the society of the spectacle and the intimately private, and how that affects the individual, moving between the territories of dominant, popular, sub- and ethnic culture, and how the nature of identity is constructed and publicly displayed. This is painting as social space.

Moving closer to the canvas, at the technical level there is so much going on: particularly the scumbled pigment applied with a dry brush that is suggestive of the ubiquitous ʻafa of the islands (the sennit fibre made from coconut husks), floating like a numinous aura in counterpoint to bolder, fluid lines in thick paint. Leleisi’uao is a testament to the AUT fine arts programme that was. He is a consummate technician, and yet is also curiously restrained and un-gestural, as if to deny us any chance of getting too caught up in admiring the paintwork.

It’s much more important that we seek connection.

Andrew Paul Wood

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.