Andrew Paul Wood – 15 October, 2018

A complex, mercurial, and often difficult man, Schoon would do much to draw attention to the Māori rock art of the South Island High Country (with an unfortunate habit of touching it up, resulting in a fall out with Tony Fomison). He was a powerful force for promoting the aesthetic appreciation of Māori visual traditions among New Zealand's Pākehā population, single-handedly reviving the art of gourd carving.

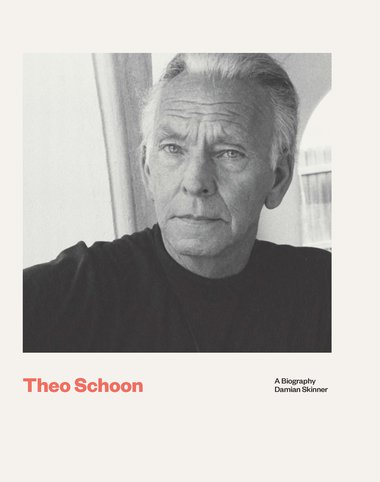

Damian Skinner

Theo Schoon: A Biography

Massey University Press, 2018

So many people, including myself, have wandered down the rabbit hole of trying to write the biography of one of New Zealand’s most important and least known artists, but finally here is the book we’ve been waiting decades for. Caveat: I provided access to my archives and gave feedback on an earlier draft of the text. Damian Skinner has done a splendid job weaving together the life of this extraordinary character. Schoon, born to Dutch parents in the Dutch East Indies in 1915, trained in Rotterdam in the painstaking traditions of Dutch Art while being exposed to the cutting edge of European modernism, and then coming to New Zealand with his family to escape the Japanese invasion of Indonesia. Here he would become a strangely influential figure on artists as diverse as Gordon Walters and Rita Angus.

A complex, mercurial, and often difficult man, Schoon would do much to draw attention to the Māori rock art of the South Island High Country (with an unfortunate habit of touching it up, resulting in a fall out with Tony Fomison). He was a powerful force for promoting the aesthetic appreciation of Māori visual traditions among New Zealand’s Pākehā population, single-handedly reviving the art of gourd carving. He also brought his unique vision to pounamu carving and ceramics, and his photographs of geothermal formations and mudpools around Rotorua are probably one of the most important bodies of art ever produced in this country.

Skinner, a consummate art historian, certainly someone in command of the information, having written about Schoon and his context over many years, is clear and objective, getting all of the facts and dramas in and in the right order - if a little dry in tone for such a colourful subject. Of particular interest to me, perhaps because I found it so difficult to research, is Schoon’s later life in Bali and Australia, although inevitably a certain amount is always going to be forensic guesswork. It’s not an easy ask of any researcher. So much of the relevant past was lost in the Indonesian revolution (and later tsunamis), in the German bombing of Rotterdam, and many of the people who knew Schoon best have since passed away. Skinner has left no resource unturned, richly complemented with photographs.

The design of this book is magnificent. I particularly like that the palette has taken its cues from the faded colour photographs of the past. Schoon died in a charity hospital in Sydney in 1985, and the art world herein encapsulated seems to be drifting into the past with ever-increasing velocity. The timing is particularly good. Schoon, a perennial outsider, foreign, exotic, homosexual, too difficult to fit into nationalist narratives of masculine kiwi modernism, finally finds his due in a glorious piece of scholarship. There are so few New Zealand publishers interested in academic art books (and that do it particularly well) that it is a tonic to see Massey University Press stepping up with such high-quality offerings.

Andrew Paul Wood

Recent Comments

Ralph Paine

O Destiny! Pantheon or crap house? Doesn’t Mr Byrt realise that composting is hot?

John Hurrell

There are some meaty opinions by Anthony Byrt on this book and Schoon's status in the latest Spinoff.

John Hurrell

This is an impressively crafted book, lucid and immensely informative. A weighty biography up there with Roger Horrocks' wonderful publication ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 7 comments.

Comment

Martin Rumsby, 11:17 a.m. 16 October, 2018 #

I think it is great that Damian Skinner has written this book on Theo Schoon and that Andrew Paul Wood has assisted him. It will be a valuable addition to New Zealand Art History. We need more people like these if we are to survive the closure of the Elam Library and Art History at Otago. If I may, I would like to clarify a couple of points. I wonder where the idea of a fall-out between Tony Fomison and Theo Schoon arose. I knew both men in the 1980s and although their aesthetic views differed from each others, there were broad areas of agreement between them. From what I saw of their relationship between 1982 and 1985, Tony Fomison was very supportive of Theo Schoon and also encouraged my interest in Theo, his ideas and work. I did witness one falling out between them, but it was not over the rock drawings but rather a social situation. (All recorded an audio tape). Schoon admitted to retouching the rock drawings to give them greater definition for his photographic documentation. (The drawings were faded and remember, up until Schoon, no one at the time was interested in them). The real issue, in fact, was not the touching up of the drawings but the crayons that Schoon used to do the job with as they permanently marked the petroglyphs. (Such was Schoon's artistic integrity and adherence to absolute veracity there can be no question that he in any way altered the designs, some of which he believed would soon be lost to the elements) As for Theo being prickly, well he had a very difficult time in New Zealand. (Strangers Arrive). I was too young and ignorant at the time to comment on Theo's views but my subsequent experiences confirmed for me his complaints in regards of New Zealand and its arts managerial and academic sectors. At heart, and despite the example of many fine NZ artists, we still persevere under the hangover an aristocratic 19th Century colonial arts society. I, for one, cannot blame Theo Schoon for the strength of his objections to what he encountered in New Zealand. Better to take him at his word than hold his words against him.

Andrew Paul Wood, 11:44 a.m. 16 October, 2018 #

The falling out between Schoon and Fomison took place in the 1960s following the publication of a paper by Fomison in which he was critical of Schoon's methods. Schoon published an acerbic response. Relations were cool for a long time after that. They made up around 1980 I think.

Martin Langdon, 10:02 a.m. 12 November, 2018 #

"no one at the time was interested in them"

I'm gonna just say that this comment probably pertains to a certain demographic, as these tohu that you speak of were 'of interest' to Ngāi Tahu Māori long before being outlined or recorded by Schoon Hamilton or anyone else.

He had his reasons and rationale for his actions that were of 'its time' but were limited to his perspective. Probably why there become some conflict with Fomison who had another perspective or cultural insight.

Useful nonetheless.

Martin Rumsby, 11:43 a.m. 16 October, 2018 #

Search Theo Schoon #1 AND Voice of Theo on Youtube to hear Theo Schoon in his own words.

John Hurrell, 4:49 p.m. 19 February, 2019 #

This is an impressively crafted book, lucid and immensely informative. A weighty biography up there with Roger Horrocks' wonderful publication on Len Lye's life, or Ian Wedde on Bill Culbert.

John Hurrell, 11:26 a.m. 5 March, 2019 #

There are some meaty opinions by Anthony Byrt on this book and Schoon's status in the latest Spinoff.

Ralph Paine, 12:10 p.m. 7 March, 2019 #

O Destiny! Pantheon or crap house?

Doesn’t Mr Byrt realise that composting is hot?

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.