Andrew Paul Wood – 20 January, 2019

In the final decades of the nineteenth century the poetic name “Maoriland” was concocted for a misty, romantic, twilight past (equivalent to the English “Albion”) where the colonists could safely quarantine what they saw as a fading Māori past. Yes, it does sound like a theme park; certainly it was at odds with actual Māori life at the time.

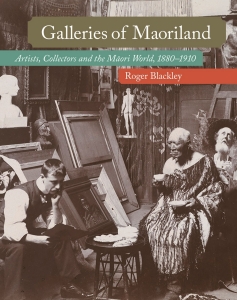

Roger Blackley

Galleries of Maoriland:

Artists, Collectors and the Māori World, 1880-1910

Hardcover, 300 pp, colour illustrations

ISBN 978-1-86940-935-7

NZ RRP (incl. GST): $75.00

Auckland University Press, October 2018

The turn of the nineteenth century into the twentieth is a fascinating one in terms of Aotearoa New Zealand’s visual culture (and culture in general) for Māori and Pākehā alike. Roger Blackley‘s Galleries of Maoriland is a thorough and insightful analysis of the uses and abuses of representation at a point in the colonial agenda when, to paraphrase Britney Spears, it wasn’t a colony and not quite a nation. In particular depictions of Māori and indigenous flora and fauna were put to propagandistic romantic nationalist purposes, not incidentally (although Blackley doesn’t touch on it) coinciding with similar trends in Europe and Britain (the Celtic revival comes to mind). Much as more recently we branded ourselves “100% Pure”, in the final decades of the nineteenth century the poetic name “Maoriland” was concocted for a misty, romantic, twilight past (equivalent to the English “Albion”) where the colonists could safely quarantine what they saw as a fading Māori past. Yes, it does sound like a theme park; certainly it was at odds with actual Māori life at the time.

Governor George Grey early on recognised the necessity of a thorough ethnographical understanding of Māori in order to rule (and assimilate) them. The export and display of Māori taonga was a way for Pākehā New Zealand to distinguish itself from other more-or-less indistinguishable British colonies, and to attract the attention of other European powers with some decorative exoticism. It is interesting to learn that the call for historical taonga to remain in Aotearoa and to be repatriated from overseas collections, goes as least as far back as 1883 in an address to the recently formed (Auckland) Art Students’ Association was addressed by its president, Kennett Watkins. This, however, was mainly with the intention of preserving them for what he saw as the colonial successors of Māori.

Blackley, an associate professor of art history at Victoria University of Wellington, and a former curator of historical New Zealand art at Auckland Art Gallery, teases out a storied saga of the many and diverse ways Pākehā “reinvented” and instrumentalised Māori in this period, in the paintings of Lindauer and Goldie and other artists, through international exhibitions and institutions such as the Polynesian Society and the Dominion Museum. Maoriland, though, was only ever a shadowy, ersatz adjacent reflection of te ao Māori. At the same time, however, Māori weren’t simply passive bystanders in this process — they were stakeholders (whether Pākehā at the time thought so or not) and actively involved with their own agendas. This is probably the most interesting part of the book.

Some Māori commissioned portraits from Lindauer because they wished to preserve themselves and their mana for posterity, fearing the worst, in a way that has far deeper, spiritual and more lasting significance than a mere painting. They had assimilated from Pākehā the notion that they could exercise some control over their own image — a powerful concept for a culture under pressure by colonisation. At the same time, however, this also illustrates the diversity and complexity of views held by Māori on the subject, as others rejected it as culturally alien, offensive to their mana, or out of spiritual beliefs.

Māori also recognised the utility in performing their traditional culture as a point of difference and point of diplomatic appeal (“soft power” as we might call it today) to colonial New Zealand’s superiors in Britain. Blackley recounts the famous story of the future Edward VII being charmed by a Lindauer portrait of Terewai Horomona dancing with poi at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition held at South Kensington, London in 1886, with it subsequently being gifted to His Highness. Māori also were quick to take to what Blackley calls the “curio economy”, producing knock-offs of their own taonga for the local Pākehā and international market, which is no more contradictory than the practice during the Musket Wars of elaborately tattooing mokai (slaves) so that their heads could be harvested, smoked and sold to Pākehā. For Māori the value lay in abstract association with mana and whakapapa, not the mere appearances that satisfied the Pākehā.

Blackley‘s thesis seems to be that many of these topics were manifestations of an emerging hybrid identity of Māori westernising and Pākehā romantically adopting Māori signifiers to distinguish themselves with a new, non-British identity anchored in New Zealand. While there is more evidence than Blackley has touched on to support this, in the evolution of a Pākehā identity (even down to the naming of children — Rewi Alley, Rata Lovell Smith, Ngaio Marsh), I can’t comfortably entertain that with Māori when Homi Bhabha’s theories are so much more compelling in how the colonised mimic the coloniser in order to be heard.

For once we have a book that gives equal attention to both main islands, and refreshingly, Victorian Pākehā aren’t presented as two-dimensional ciphers of imperialism and postcolonial theory, but rather as complete characters no better and no worse than they should be. It’s also worth noting (as Blackley does in his preface) that this is a book by a Pākehā art historian with a particular worldview and unconscious biases. A book written by tangata whenua would be very different, and I hope a Māori scholar will take up that challenge.

Andrew Paul Wood

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Roger Blackley has just died after a short illness: a huge loss for the Art History Department of Victoria University. ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 11:07 p.m. 15 May, 2019 #

Roger Blackley has just died after a short illness: a huge loss for the Art History Department of Victoria University. An energising and vivacious, greatly loved lecturer, it will take some time for staff and students to recover. An exceptionally convivial and generous teacher and scholar.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.