John Hurrell – 30 May, 2019

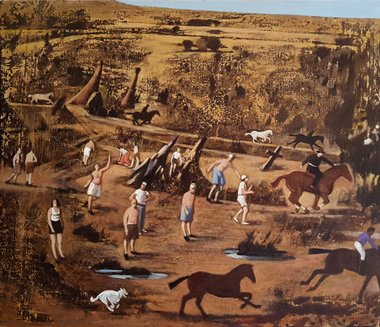

When the dry landscapes have a plenitude of diminutive figures set in groups against rising hills or terraces (and often facing the painter), the effect is a little like musical notes in a stave, bobbing up and down. They are formally posed narratives that with their compositional rhythms double as visual ‘scores'.

The unusual title of this collection of recent paintings by Richard McWhannell comes from a town encountered by the artist and his family during a recent trip to New Mexico and Texas, suggesting that truth (through the integrity of personal action) is part of the urgent endeavour that drives the artist—even though art itself is an anthropological construction: in a sense, a lie. One that diverts and entertains us as we gradually approach death.

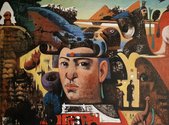

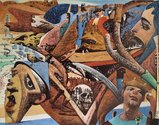

Often Surrealist in mood—deliberately cluttered with absurdities like distorted bodies hovering in mid air—and rich in allusions to other artists like Fomison, Clairmont, Palmer, Bruegel, and Tenniel, the show of ‘landscapes’ is exciting because of McWhannell‘s testing out of spatial layering; regularly using some of the texture-generating techniques developed by the great innovator Max Ernst. We see him incorporating unexpected visages, like that of Oum Kalthoum (the legendary Egyptian singer), with much smaller figures, such as himself and his immediate family.

The layering is achieved by placing the geological and narrative elements on top of organic textured grounds which serve as speckled or grainy underpainting. These gritty areas therefore peek through the gaps in sections of dryly and coarsely brushed-on oil paint, constantly reasserting the presence of the picture plane, no matter how strong the illusory depiction of receding space on top.

When the dry landscapes have a plenitude of diminutive figures set in groups against rising hills or terraces (and often facing the painter), the effect is a little like musical notes in a stave, bobbing up and down. They are formally posed narratives that with their compositional rhythms double as visual ‘scores’.

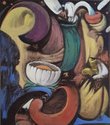

Some of McWhannell‘s other works, the Surrealist ones, are extraordinarily wild, such as Barkskin with its synthesis of Fomison, Ernst, Clairmont and Lynch. Blending SciFi cinema with a little geometry and some chopped up—reshuffled—exploding narratives (set in an early McCahon landscape), it is terrifying but also subtly erotic; we see a woman’s leg protruding from a giant puff of smoke into which a ghostly Baconesque figure seems to be walking.

Sometimes in his crazed (but fragmented) eclecticism the artist utilises a strange compressed feel from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Sir John Tenniel’s book illustrations, mixed in with a bit of Punch and Judy. In some, where much larger distorted heads are involved—and the aether is awkwardly thick with grotesque flying objects, pushing and shoving—leering three-quarter angled faces confront the viewer. Others with side profiles are less effective. The outlining edges dominate and look cut-out and flat.

Outside of the absolutely brilliant lopsided Barkskin, the best works are not overly frenetic, playing off dense bodily activity against airy spaciousness in a coordinated fashion—without being too ordered, too inevitable. Chaos somehow is invited in, yet restrained. The hot ‘New Mexican’ air crackles with energy, embracing McWhannell‘s theatricality and dodging any whiff of the formulaic.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.