Andrew Paul Wood – 30 September, 2019

It's interesting to see how the paintings develop stylistically in their influences from Cézanne, through Picasso's Analytical Cubism and probably Orphism, and then Mondrian's early deconstructions of figuration into Neoplasticism. We get to see McCahon's environmental concerns, which otherwise haven't been well documented.

Peter Simpson

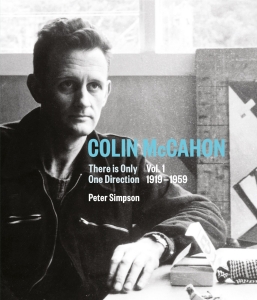

Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction, Vol. I 1919-1959

Hardback, 368 pages, colour illustrations

Auckland University Press 2019

ISBN 9781869408954

RRP: $75

August this year marked the centennial of the birth of Colin McCahon, coinciding with the release of this spectacular first volume, Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction, 1919-1959, of what will be a two-volume publication on the artist by Peter Simpson. The title, There is Only One Direction, is shared with a powerful monochromatic Madonna and Child painted by McCahon in 1952, now in the collection of Christchurch Art Gallery, but it was also something McCahon frequently said about the singlemindedness of his modernist artistic development. It brings together two of the artist’s chief preoccupations — the pursuit of his art and his wrestling with spirituality.

When Marja Bloem, then curator at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, referred to McCahon as “de Van Gogh van Australasia” while talking about the motivation behind their exhibition, Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith in 2002, she was overegging the cake. Still, not bad for a boy from Timaru, and this is very much a book that does the artist justice.

In terms of first impressions of design and production it’s pretty damned lush. The cover is textbook Spencer Levine-style—aqua-toned palette and sans serif font on an unbordered black-and-white portrait of the artist—and the hardcover volume is generously illustrated in colour with excellent colour reproductions. Visually it’s a stunner, and anyone who has been following Simpson’s progress on Facebook will be aware of how thorough his research has been.

Clearly this is intended as a comprehensive work, and yet you might fairly ask yourself, is there really anything left to say about McCahon? The answer is a resounding yes. The reason is because much art publishing in New Zealand has a distinct North Island (and specifically Auckland) bias. The most frequently reproduced Bill Sutton painting is Nor’wester in the Cemetery (1950) precisely because it’s in the collection of Auckland Art Gallery. Despite McCahon living exactly half his life in Te Waipounamu, art historically the south often remains terra nullus causing many to regard the second half of his career as the most important phase in terms of his achievements. The epicentre of Pākehā cultural production moved north at the same time McCahon did, which McCahon commented on, as Simpson notes.

That blind spot started to change around 2016 with Simpson’s Bloomsbury South: The Arts in Christchurch 1933-1953, and Warren Feeney’s CSA: The Radical, the Reactionary and the Canterbury Society of Arts 1880-1996 being much needed correctives, while I have gently been pushing the idea that New Zealand regionalism survived nationalist modernism well into the 1990s and possibly today. Multi-volume projects allow for expansiveness, and at least half of this first volume is dedicated to McCahon’s South Island life and development, with meticulous context and accessibly articulated.

It’s an intimate look into the background of McCahon’s religious-themed paintings and the artist’s ambiguous beliefs. There is also a lot of fascinating detail around how he accessed historical European art through publications, and his 1951 visit to Australia, funded by Charles Brasch.

During this trip he studied the quality Old Masters in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, and took lessons with the elderly Scottish-born Cubist Mary Cockburn Mercer (1882-1963). Mercer is a fascinating character, a member of pre-First World War avant-garde circles in Paris, and had attended the infamous banquet Picasso threw for le douanier Rousseau at the Bateau Lavoir in Montmartre in 1908. I’m a little disappointed that a little more space couldn’t have been spared elaborating on this fascinating character.

The second half of the book is mostly taken up with the Titirangi years and McCahon’s unique vision of the Waitakeres in their prospect of now-threated kauri. This dips back into territory Simpson has covered in more depth in his 2007 book Colin McCahon: The Titirangi Years, 1953-1959.

It’s interesting to see how the paintings develop stylistically in their influences from Cézanne, through Picasso’s Analytical Cubism and probably Orphism, and then Mondrian’s early deconstructions of figuration into Neoplasticism. We get to see McCahon’s environmental concerns, which otherwise haven’t been well documented. If one was going to be extremely pedantic with a very minor cavil, Simpson describes a group of stylised nudes fused with kauri forms as a “young kauri metamorphosing into voluptuous female bodies as if in reversal of the Diana myth (woman into tree, becomes tree into woman),” one assumes this is a confusion with the nymph Daphne turned into a Laurel to avoid rape at the hands of Apollo.

It’s wonderful to see McCahon’s lithography getting full consideration as well. It’s also in this period, ca.1953-1955, that McCahon painted his glorious French Bay that is in the collection of Auckland Art Gallery. I’d like to draw a link with his friend Doris Lusk’s painting of the same scene from around the same time, with its McCahon-esque pseudo-Cubist painting within a painting. One wonders if this was more than a coincidence.

The book concludes with the text works, the Elias paintings, The Wake, the Northland Panels, and the beginning of McCahon’s mature style, which seems a sensible point to split the volumes. Simpson perfectly conveys how radical these works are, while still being anchored to place, and uses extensive illustrations. It manages to set the reader up for later developments without foreshadowing too much, and spoiling anticipation for the second volume.

I can’t wait.

Andrew Paul Wood

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.