John Hurrell – 1 September, 2021

With these six works (called 'Untitled' by the artist)—I've chosen here to differentiate them by using the caption at each drawing's base—they can be listed as such: 'FIG. 44 types'; 'fig. 45. - Différents'; 'fig 44 (other bodies)'; 'fig. 44 bodies'; 'Fig.1'; 'Untitled'. Like Cullen's airborne sculpture, these drawings ‘pull the carpet out' from under rationality by shuffling around (to confuse) elements of strict logic, universally agreed factual occurrences, and nuanced (but clearly false) absurdity.

Within this lockdown situation, there are three sorts of exhibit I want to think about in this Paul Cullen show, put together by his estate with Alan Smith and Marcus Moore, the editors of a new publication on his practice. Obviously my attempted description of what I consider to be plainly visible, is inseparable from a parallel activity: my attempted (speculative and sometimes skimpy) interpretations.

First of all there are six black silhouette drawings on white sheets ostensibly dealing with plans for an orchard in a garden. Many are formally organised, with geometry a salient factor, and include lots of elements from the world of physics, astronomy and horticulture. I want to make some observations mainly about them.

These silhouette works can be taken as jokes about constructing drawings and organising gardens by implication; snorting not only at rationality but also at representation, and sympathetic perhaps to Nelson Goodman‘s rebuttal of all claims of ‘natural’ correlation being present in ‘imitative’ forms of signifying, especially drawing, which he saw as symbolic.

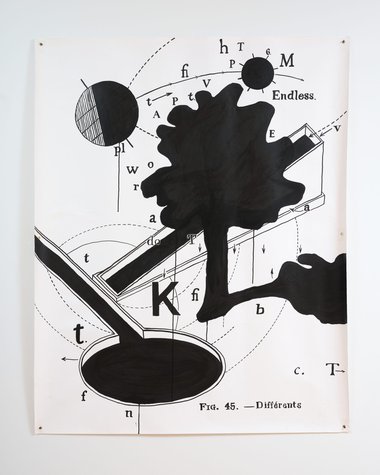

With these six works (called Untitled by the artist)—I’ve chosen here to differentiate them by using the caption at each drawing’s base—they can be listed as such: FIG. 44 types; fig. 45. - Différents; fig 44 (other bodies); fig. 44 bodies; Fig.1; Untitled. Like Cullen‘s airborne sculpture, these drawings ‘pull the carpet out’ from under rationality by shuffling around (to confuse) elements of strict logic, universally agreed factual ‘scientific’ occurrences, and nuanced (but clearly false) absurdity.

In the first four, light and gravity are persistent themes linked to the continual presence of the Sun (though not depicted) and Moon; The Moon attracts tides in its gravitational pull (towards itself) and the Sun casts visible shadows (away from itself). Around them swirl clouds (like mosquitoes) of irritating lower-case letters and oddly directed arrows that clog up your understanding of what you are looking at, instead of helping.

In FIG. 44 types an ambiguous interpretation of a tall towerlike structure allows it to be a civic monument (that can be used for measuring the changing speed of dropped objects) or lighthouse (for emitting light to further safely scientific observation). Between the top and bottom paper edges the skinny construction is split in two—perhaps a laugh about its ambiguous identity—but in fact a looping compositional device sometimes used by Jasper Johns.

This drawing of Cullen‘s also has an avenue of eight trees (four each side) disrupted by a shambolic positioning of irrigation ditches which are almost perpendicular to each other, and not connected up, even though the Earth’s crust is very thin as if it were a flat piece of plasterboard. We notice too the two dotted images of a spinning planet. With the horizontal bands, maybe it is Jupiter. Plus in this drawing there are vertical thin lines that as mock drips allude to a gravitational pull on the ink, especially if it is applied when the paper is vertical.

fig. 45. - Différents presents a tree shaped like a hirsute thinking head, casting a shadow. (Could it be Georges Perec, alluding to ‘Species of Spaces‘? Or ‘Things‘?) And a ditch cut out with a jigsaw is shaped as a bulb-ended thermometer—as if the temperature of the soil is to be measured and valued. The trees (individually or as communities in orchards) seem to be metaphors for ordinary human lives, and the linked shadows the impact of their cultural contributions (averaged out?) over time.

Also in this drawing, a thin water-filled ramp based on a right-angled triangle has its tilted liquid not spilling out of the hypotenuse, while once more we find vertical thin lines that as mock drips allude to a gravitational pull on the applied ink. There is also at the top, a solar eclipse where the Moon blocks out the Earth’s visibility of the Sun, but in the bottom half of the image there seems to be ordinary daylight—with cast shadows.

In (fig 44) other bodies (also labelled Sketch of the outward appearance) we see another ‘Perec’ tree, a simple brick building, a gravity-exerting new Moon (it can’t be the Sun because the shadows are not so aligned) that affects the Earth, a sealed off reservoir which seems to be a container of all human knowledge, and three oddly aligned functionless ditches; whilst in (fig.44) bodies we find a full and accessible ‘knowledge’ tank, a rotating moon, and three more oddly positioned ditches that prevent the presence of a fourth tree (there are three). They take up the contested space, leaving only an imagined dotted arboreal outline.

Note too, that in three of these drawings the word ‘Endless’ occurs, twice hovering over cylindrical tanks and once connected to an orbiting Moon. Does Cullen mean the measurements here are infinte? Or standing for endless ignorance or endless futility instead?

Looking at the other two images, Fig.1 displays a spade-shaped irrigation ditch, a watery digging tool leading into four horizontal rows of fruit trees, bearing spindly letters as fruit. The orchard trees bear figs. (ie the brief numbered captions commonly used for diagrams or pictorial illustrations) while the oblong blade for digging trenches and planting replaces a missing unplanted tree and takes over the central square space.

In the last Untitled (comparatively uncomplicated) drawing, the tilted square orchard (casting uniform shadows) is bisected by not an angled irrigation ditch, but a wider canal that passes under a bridge. It does not align with the perfect centre of the space, but carelessly leans to one side. Repeated and jumbled sequences of mysterious cursive fig. letters pepper the sides of this wide invasive diagonal trench.

On the gallery floor we see two freestanding sculptures of diffuse pencil towers ascending from unusual ‘plinths’; one wooden (a skinny tubular desk that doubles as a low ladder), the other a foldable canvas chair with a hole cut into its seat. The ‘Tatlin’ pencil clusters-on these rickety furniture bases—besides referencing Anthony Gormley’s ‘ethereal’ bar sculptures, seem to allude to humankind’s accumulated knowledge, specifically its recording using correctable graphite-written documentation.

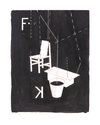

There also six black inked drawings of various household objects like buckets, chairs, globes, tables, books, and bookcases, suspended in space, rendered with unpainted ‘white’ lines. Casually composed, ad hoc style. Working studies for examining possible combinations.

These black drawings have links to British artists like Tim Head or Michael Craig-Martin with their interest in portable domestic items, but now they function as preparatory aids for Cullen‘s suspended or pinioned sculptures, where with height and (sometimes) inversion, he subverts any functionality they might have once possessed. Once loved, these recycled artefacts will soon become abandoned in the lofty architectural aether, to make an anti-materialistic, anti-bourgeois, anti-consumerist, anti-science, neo-dada gesture.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.