Andrew Paul Wood – 26 October, 2009

Field Work feels a little like a minimalist stage set representing a sort of camp site – diagrammatic, illustrative, allusive and suggestive with just a hint of a steampunk aesthetic.

Christchurch

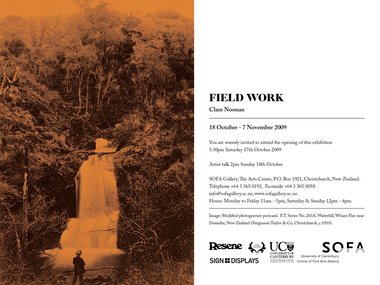

Clare Noonan

Field Work

18 October - 7 November 2009.

And do you see, I said, men passing along the wall carrying all sorts of vessels, and statues and figures of animals made of wood and stone and various materials, which appear over the wall? Some of them are talking, others silent. You have shown me a strange image, and they are strange prisoners. Like ourselves, I replied; and they see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave? [Plato, Politeia VII, 515b]

Clare Noonan’s Field Work is the product of the artist’s tenure as the Olivia Spencer Bower artist-in-residence in the Christchurch Arts Centre. Noonan’s work is singularly concerned with mapping the artist’s body located in geographical, historical and cultural space in a manner bordering on the Situationalist. In the Field Work installation, this is counterpointed with the history and nature of photography, and specifically its virtual relationship with light. One is reminded that Karl Marx once compared the function of ideology to the mechanism of a camera obscura:

If in all ideology men and their relations appear upside-down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process. [Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology(1976)].

In this sense a camera is like an ideology because it produces an image of the human relationship with the world, but further themes must include the relationship between the viewed and the viewer, what is visible and what is obscured, and the ephemeral and transitory reality of occupying any space.

Field Work feels a little like a minimalist stage set representing a sort of camp site – diagrammatic, illustrative, allusive and suggestive with just a hint of a steampunk aesthetic. From tripods that look like they might be from some ancient surveying kit, hang hurricane lanterns fitted with moon-glow black-light tubes. These light sources provide numinous accents to counterpoint the minimal concrete nature of the other artefacts. Something like a photographer’s hide or maimai hangs off two tripods. A half open suitcase emits a mysterious light (like the trunk of the car at the end of Repo Man). The whole is connected by a baroque tangle of electrical cable.

On one long wall a kind of backdrop is formed by hanging three hide sheets, which in one sense suggest animal skins (if we think of a maimai as a sort of animal), but on the white wall of the gallery also conjure up art-historical memories of the iconoclasm of modern monochrome field painting: Arnulf Rainer, Allan McCollum, Imi Knoebel, Ad Reinhardt, and Kasimir Malevich…the list is endless.

On the opposite corner of the gallery hang what appear to be four monochrome prints or mechanical drawings alluding to photography text book diagrams depicting overlapping circles of light on flat surfaces. In fact these are connected to a picture in the accompanying catalogue of a drawing in one of the artist’s notebooks. The drawing is a Venn diagram that attempts to place the role of ‘Explorer’ where ‘Artist’, ‘Scientist’ and ‘Entrepreneur’ intersect.

That would appear to be the key to understanding the installation – it is a metaphorical camp site (abandoned Marie Celeste fashion) in the re-contextualising sterile white cube of the art gallery setting. Another picture in the catalogue (and really, the catalogue must be considered intrinsic to the installation, complete with a rather nice essay by Paula Booker) shows a number of those plastic name tags ubiquitous at corporate functions, announcing the presence of Joseph Banks, Walter Buller, Alfred Burton, Samuel Butler, Charles Heaphy, William Travers and others.

This connects back directly to the Claude glass in Noonan’s exhibition Pilgrim Tourist at Enjoy Art Gallery, Wellington and the compass references in Landscape Portrait at The Physics Room, Christchurch in 2007.

Dasein (literally ‘being there’ in German) is Heidegger’s term for the way beings relate themselves to the world that surrounds them, but from which they are existentially alienated. It seems the perfect definition of the Pākehā context and the mood evoked by the representation of landscape.

Heidegger divides Dasein into three modes of possible existence — factuality, existentiality and fallenness. The first of these could be used to describe the status of the first European colonists in New Zealand, the first generations of Pākehā, or even the Pākehā experience of Europe. The second refers to the state in which beings achieve knowledge of their purpose in life and the resultant authenticity – arguably the current historical phase. The third refers to the inauthentic existence of those who do not realise their purpose – the reality of many Pākehā whose lack of knowledge blinds them to the nature of their anxiety and the urban Māori who have become divorced from their status as tangata whenua.

In any discipline field work is carried out either unobtrusively in situ on location, or in a controlled laboratory environment. Which of these two options applies to Field Work? Or is it even a case of qui custodiat – “who watches the watchers?”

(Above documentary images: Tim Veling for SoFa Gallery)

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.