Creon Upton – 27 June, 2010

Oliver notes that his source images all come from the internet, which is no great surprise. And what's interesting about the show is its dedication to the analogue: these objects represent a translating-back-into, a return to the cold world where we cannot be warmed by a digital fire, where materials matter and honey-on-window has consequences.

Christchurch

Oliver of the Sky

Favourite This

18 June - 12 July 2010

Upcoming HSP shows might well feature live ant trails, which will look cute alongside whatever hessian sacking or valentine’s wrapping’s been strewn across the floor and is passing itself off as sculpture, or an installation.

That’s because at the moment something there passing itself off as sculpture, or an installation, involves a pottle’s worth of honey smeared over a north-facing window. And, thinned by these frosty-nights’ condensation, it’s slathering its way down the walls and is dribbling quietly into the showroom below.

But especially when the sun shines on it, it reveals that particular glistening allure of foodstuffs we must not go near, with their ambiguously threatening stickiness known to signify wickedness and the possibility of violence. It’s for looking only: no touching - almost as if it were real Art. Thus, seamlessly, edgelessly, child- and adult-hood, and their objects of desire, are conflated by this globular display.

Myself, I’m pure generation x, coming from right at the heart of that couple of decades. When folks of mid-eighties vintage started showing up in the adult world I knew I was immediately and categorically not at home in any realm even vaguely claiming to be hip.

It’s not about being old; it’s about being an old person.

Oliver of the sky, the artist in question here, is a young person, at least for the moment, and he thinks about generations, making me think about generations - which I admit is a pretty cheesy discourse to be buying into.

This whole generation-talk - x, y, z - it’s the ultimate work of capitalism and the tidy deal it struck with the impresarios of an age. From high modernism to low consumerism, making it new remains the paradigm of our time. And now that attaches itself to our perceptions of youth, transforming what was once simple burning-nostalgic-desire - and its handmaiden, old fashioned fear-of-death - into a perception of something actually significant going on. Ridiculous, surely.

But then reading the conversation between Oliver and John Lazer that accompanies the show, where they talk about GIFs, tagging, and whether it’s possible to ironically, self-consciously return to Radiohead, it’s very difficult not to believe that there might actually be something going on.

It’s the internet, basically. This is embarrassing. I feel like some Humanities professor from Berkeley back in the 90s writing papers about the democratising potentials of the “information superhighway”. The important change is in the ontology-status our technology claims for itself: no longer an autonomous, inanimate other that we humiliate ourselves before, technology is finally becoming (merely) a medium in which we exist. And for the generations whose main learning took place before Wikipedia, it’s difficult to know how to breath freely in this atmosphere. But it’s nothing unprecedented: any carpenter has the same relationship with her tools. It’s that peasant’s shoe that Heidegger talks about: it’s a living intimacy with the other.

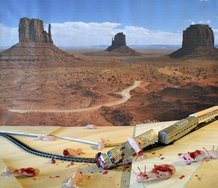

So, Oliver’s show? It’s dominated by a bulky great piece of black polythene, strung up and hanging awkwardly like a child’s nightmare-image of badness. Behind that is the window of honey. There’s the sheet of clear plastic, soft and light like surgeon’s gloves, taped to the floor and billowing slightly with the updrafts. There are some cut-outs on a window, a crumpled print with SKATE ACIDAL on it discarded in a corner. And there are six white-framed paintings.

And projected onto the polythene monster is a video loop of a fire, flickering gentle flashes of colour, drawing our gazes like any promising light against the infinite blackness of a night-, or C₂H₄-, or www-sky.

It all seems a bit random: various items from an adolescent’s bedroom uplifted, transported, and installed in space.

Oliver notes that his source images all come from the internet, which is no great surprise. And what’s interesting about the show is its dedication to the analogue: these objects represent a translating-back-into, a return to the cold world where we cannot be warmed by a digital fire, where materials matter and honey-on-window has consequences. These arbitrary mementoes of a teenage male human being’s life sit oddly in space because they are here to remind us of space, that we live in space, with and through objects, moving and being moved, always around discrete items of stuff.

So, yes, there’s this generation thing going on, undoubtedly. But there’s also a nostalgic, affirming sameness about this unselfconscious revealing of what it means to be a kid. The honey is some misconceived scheme gone all wrong; the print is an embarrassing leftover from two months ago, childish and repudiated; and the polythene fire-screen is an elaborate project wrought in plastic, gaffer tape and string.

And the paintings.

Here they are, and despite all attempts to avoid it, there’s this frank admission hanging sedately and respectfully on the wall that we’re also in the presence of an artist here who’s actually taking himself quite seriously and wants us to too. And there’s the same stuff going on here as in the installation as a whole: small, arbitrary remainders from a day’s living (images that have tumbl’d by) seized and held in a place long enough to become part of a space, to remind us of space, to let us think about space and colour and place and shape, pattern and design and what it feels like to look at something really nice that might not let us down. Like a skateboard, or a carburettor, or a chain. Or especially a flame.

There’s something really quite heartbreaking about these simple, careful, obsessive watercolours which seem somehow to have been uplifted and remastered from the back pages of Oliver’s fifth form exercise books. Nike logos in blue biro, remembered and re-rendered fairing decals in orange-yellow flame, Kawasaki lettering got just right. And abstract murmurings in colour and line. There’s a not-yet-ashamed-ness in the air. There’s a purity of single-minded, unreflective meandering, curiosity and exploration. A painting is scorched with ACAB, which stands apparently for All Cops Are Bastards.

Rebel rebel.

Creon Upton

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.