John Hurrell – 28 July, 2010

According to some of the London images, that rock wall is also paper thin - an ersatz prop just as the free-falling birds are only feathery fleeces. Sometimes Cotton shows an archway cut in the granite and its edges pulled apart, to reveal the cliff as a mere painted sheet suspended in the void. Cotton is testing us here with his surprising twisting of his symbols, contemplating the falseness of the ostensibly solid physical world and mocking also perhaps the profundity of its signs as ‘high art'.

It is a while since Shane Cotton last showed his paintings in Auckland: not since Victoria Lynn’s Turbulence triennial of 2007, and his mini-exhibition in the New Gallery. So this current display shows us where his work has moved in three years (if at all) and is concurrent with a very similar exhibition in London at Rossi and Rossi. He presents at Lett’s four canvases and six works on paper.

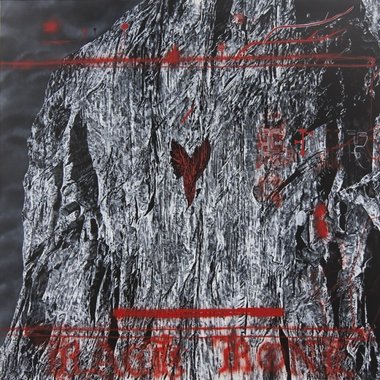

Like the Turbulence exhibits the stretcher works are dark, cinematic and use symbolism that often is not specifically from Aotearoa: against a backdrop of ominous dramatically streaky grey clouds are granite cliff-faces and hovering birds that seem vaguely based on hummingbirds. With the new work he is also using Maori language once again, that is airbrushed on so it looks like wispy smoke, ethereal, sometimes crossed out and other times indecipherable. Whilst in Lett Te Reo dominates, English is the most prevalent in London. Often he quotes lines from The Lord’s Prayer.

My sense is that the two main symbols are spiritual in preoccupation. The tumbling birds could be human souls trying to find an afterlife paradise. They might be in one stage of many reincarnations, for there seems to be hints of anamorphic distortion where something is visually resolved at the correct viewing location. Their feathery bodies look like stretched pelts, ornithological hides that can be worn like cloaks by future travellers, material bodies worn by transmigrating souls. Sometimes there are cages nearby - not for shelter or rest, more warnings of confinement or forced restriction.

The cliff faces seem to be mineral body parts of a much large human shaped entity. (A face or spine of perhaps Jesus?) They also appear to be an impenetrable barrier, a crystalline rock wall that resists soft fluffy life-forms.

According to some of the London images, that rock wall is also paper thin - an ersatz prop just as the free-falling birds are only feathery fleeces. Sometimes Cotton shows an archway cut in the granite and its edges pulled apart, to reveal the cliff as a mere painted sheet suspended in the void. Cotton is testing us here with his surprising twisting of his symbols, contemplating the falseness of the ostensibly solid physical world and mocking also perhaps the profundity of its signs as ‘high art’. The work also seems to hint at a profound interest in North American ‘First Peoples’ culture. (I say that because of some of the pictographs, the cliff face [perhaps referring the Grand Canyon] and the hummingbird), and with the textured cliff, the methods of Surrealists like Max Ernst.

Most salient are three enigmatic linear components: a drifting, dematerialising cursive script (standing perhaps for revisable religious truth) that sharpens into legible clarity or disperses into gas, the converging furrow-like grey clouds (nature) that rumble across the sky, and the meandering ‘tribal’ pictographic elements (visual culture) that in their paint quality, for Cotton, are unusually raw. The tracking brushmarks are in fact slightly oafish, a little clunky, and with the occasional dribbling air-brush squirt disconnected from any writing, a calculated reference to the materiality and process of the work’s production. The frail skinny lines seem to be about drawing and the ‘drawing forth’ of thought with its attendant tropes, looking at how we define sentient processes, how the edge, the ‘perimeter’ of self-conscious cognition can become a ‘parameter’ of the observed world.

I wonder if Cotton in these works in engaging with a reworking of or a dialogue with McCahon by presenting some sort of crisis - of religious faith (cliff-face as ‘Gate‘), of Maori or Nga Puhi identity as brand, of language using or even artmaking itself as marketed persona. There seems to be an avoidance of certainty here - a mood that is mentally skittish. All assumptions seemingly are currently being reassessed.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.