Andrew Paul Wood – 7 August, 2010

Greig is not above poking fun at the historical tradition behind his craft. Rockürer (2010) is a somewhat stylised version of Dürer's iconic woodcut of praying hands. Dürer is almost the patron saint of printmakers, both in terms of his artistic achievement and his elevation of the print to a democratic form of high art - an appropriate homage for an artist keeping the faith alive.

Jason Greig’s exhibition Reformation at the Brooke-Gifford Gallery is a rebirth of sorts after a hiatus of troubled times and inner demons. It is still, however, work uncompromisingly typical of Greig’s oeuvre, by a grandmaster (and I do not use the title frivolously) printmaker, who in many ways would find a more natural home a hundred and ten, twenty, thirty years ago in company with fellow artists Victor Hugo, Odilon Redon, Alfred Kubin, and Charles Méryon at his most insane. That would, however, deprive Greig of his beloved stadium-operatic heavy metal (perhaps Wagner was the historical equivalent). Greig plays a Fender Stratocaster in the art band Into the Void.

Greig, standing outside trends and movements, invests a haunting nightmarish quality to his works, exploring the dark places of the New Zealand heart with ambiguous gothic narratives of isolation, menace, melancholy, and a sharply morbid, sardonic wit. A graduate of the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts in 1985 with Honours in Engraving, his talents have been well recognised with work held by Te Papa (Wellington), the Hocken Library (Dunedin), Christchurch Art Gallery and the Aigantighe (Timaru, his birthplace and home town though he lives in Lyttelton). He was suitably celebrated with the 2006 survey exhibition The Devil Made Me Do It at CAG., and also participated in the very recent Sydney Biennale.

“Like music,” Redon once declared, “my drawings transport us to the ambiguous world of the indeterminate.” It is a sentiment equally applicable to Greig. His images are more passive and melancholic than Goya’s, and less concerned with constructing an illusory perspectival space than Piranesi (even less so in these works than in the past). His spaces oscillate and his indefinite imagery perhaps conforms to that which Derrida describes as a “double mark” - in that every signifier is unavoidably supplemental to other elements, open to multiple readings, and thus irresolvable.

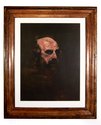

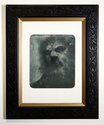

Post-Structuralism and hermeneutical/metaphysical dislocations aside, at the same time these images stoically conform to the tropes of Academic tradition. The centrality of the human figure is paramount, underscored by proficient time-honoured draughtsmanship. This ranges from work resembling the sort of dour Victorian portraiture one half expects to see the eyes move in as in Descent into Sainthood (2010), to Empathy… The Lost Monster (2010) which resembles what might have resulted if Lon Chaney’s wolf man had sat for a Daguerreotype.

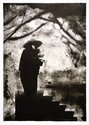

There are the small, but no less deft face studies (I am not sure it would be right to call them portraits, which implies a human original) on dish-like ceramic tondos Mythos, Hydra, and Devil’s Advocate (all 2010) And then there are the diabolical figures of works like Hive of Hums (2010) - a sort of demonic bee keeper, judging from the hat, and Omega’s Way (2010) which has the feeling of a Harry Clarke illustration of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Cask of Amontillado” or “Masque of the Red Death”.

Many of these works are complimented by ornate vintage picture frames which further enhance the impression that these images are somehow ahistorical, anachronistic and out of time. Greig unifies mounting and print into a single integrated art object. The effect is complete and contiguous. Other prints are unfussily displayed in Perspex mounts, which will more likely appeal to the inhabitant of more minimalist spaces of contemporary decor.

Greig is not above poking fun at the historical tradition behind his craft. Rockürer (2010) is a somewhat stylised version of Dürer’s iconic woodcut of praying hands. Dürer is almost the patron saint of printmakers, both in terms of his artistic achievement and his elevation of the print to a democratic form of high art - an appropriate homage for an artist keeping the faith alive. Possibly we might even read it as some sort of ex voto image. Artistically it is almost certainly a superfluous gesture, but in the context of Greig’s work it is spot on.

My final (and probably redundant) impression of Greig’s work is of something expertly executed and illustrative, but always lacking a story to illustrate - which is perfectly fine by me.

Andrew Paul Wood

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.