Mark Amery – 8 October, 2010

Purchase one of Ah Kee's surfboards and you're not only going to be standing on a tribal shield, but on the other side you'll have Ah Kee's drawing of his own half face staring back at you, as if to question why you have turned him to the wall or the sea bottom. One side represents an indigenous identity, the other himself.

Wellington

Vernon Ah Kee (Deane Gallery)

27 September - 15 November 2010

It’s surprising how slight a profile work by contemporary Aboriginal Australian artists has in New Zealand. Whether this is mainly symptomatic of visibility issues within Australia itself, or partly the vagaries of the shipping channels across the Tasman is, given the limits of my knowledge, hard to ascertain.

Beyond City Gallery’s excellent survey of Tracey Moffatt ten years ago and a rash of Asia-Pacific orientated exhibitions at the Adam Art Gallery a few years back, under Sophie McIntyre’s directorship, we’ve seen very little in Wellington. In Auckland it was a pleasure to see Richard Bell’s provocative, classy and very witty video work included in this year’s Triennial.

Roundabout at City Gallery Wellington features a number of indigenous Australian artists, including Brisbane’s Vernon Ah Kee, but the global whistle-stop format of the show doesn’t let you get too close to the ideas being expressed. The gallery display is complemented however by Ah Kee’s first New Zealand solo showing, in the Deane Gallery (part of City Gallery) until mid November.

I first encountered Ah Kee’s work alongside that of Bell’s on Cockatoo Island at the 2008 Sydney Biennale. Featured were his large charcoal and pastel portraits of his family. They had had far greater power there in a found industrial site, emerging from the impersonal gloom as specters of the past and present than they do in a small white gallery space in Wellington. Even better on the island, and a highlight of that Biennale, was Ah Kee’s commandeering as found artwork of an old wharfies toilet block. Ah Kee violently ripped away the partitions to reveal a barrage of horrendous racist and homophobic graffiti which packed a terrifying collective punch. Again the City Gallery showing is far too polite in its provocations by comparison.

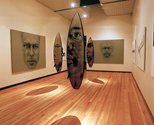

Ah Kee went on to show an installation of video work, surfboards and large wall slogans entitled Cant Chant as part of a showcase of emerging contemporary Australian art at the 2009 Venice Biennale. This makes up part of his City Gallery show and was inspired by the Cronolla riots of 2005, which saw Anglo-Australian surfies attack Lebanese Australian volunteer surf life savers, accompanied by the chant “We grew here you flew here”. The irony of this, together with Aboriginal Australians near invisibility within Australia’s beach cultural image, is something Ah Kee goes into in a slick, highly-waxed exploration of design, film and advertising’s logos and imagery, playing with the double meanings of slogans and badges of identity.

Bringing together elements of Cant Chant with three of Ah Kee’s drawings, the City Gallery show feels cramped and not as coherent as it could, like a crowded amalgamation of several bodies of work. The facial portraits aren’t given strong placement and sit cheek by jowl with the slogans to no strong effect. Inexplicably the three channel video work is hidden in its own area so it doesn’t interact with the rest of the exhibit.

I like the confrontational yet complex stance of Ah Kee’s approach, each work - whatever the media - a shiny shield that bears an emblem but which then pulls out from behind it a more knotty story.

In a modern Billabong surf apparel-like advertising font, the texts complement the dual sides of a surfboard to assert that every slogan can be flipped to state something else (‘Everyday I achieve something because I was born in this skin/ Everyday I concede something because I was born in this skin’). The work asserts the complex duality of anyone’s cultural identity: I am an individual, but I am also part of a tribe; I am Australian, but I am also Aboriginal. The text ‘first person’ at the entrance to the exhibition could be a protest banner for indigenous rights but it also flips over to introduce the entire exhibition as one person’s subjective perspective.

In focusing on surfing culture (and in a more recent work - not in this show - cricket) Ah Kee’s work notes Aboriginal Australia’s pitiful absence from the centre of contemporary Australian culture. Yet, rather than allowing it to be co-opted from the margins, by brightly decorating his surfboards with a tribal rainforest design he boldly presents an appealing mainstream alternative.

In the video work, the bright colours of Aboriginal culture meet those of the surfer as three Aboriginal surfers in shades and bright yellow jandals coolly step onto the Surfers Paradise foreshore and survey the break. They’re like colonialists assessing new territory for danger, but with the familiar viewpoint reversed so they emerge from a possessed interior terra firma, rather than the wide open seas. Comically, there’s the air of a Western showdown or a Sopranos-style mafia posse. In the video’s second part we watch a champion Aboriginal surfer ride the waves, weaving in and out and diving down into, and up out of the water, free of all typecasting and restraints.

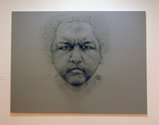

Visually Ah Kee’s work seeks to baldly counter our comfortable expectations of Aboriginal art as domestic wall commodity (indeed I find that the canvas mounting of these works - rather than their direct application to the wall - mutes their impact, as does their location in a confined white cube gallery space). The large texts (the words running together to make you slow and focus to absorb them), and eyeballing by the subjects of these lively drawings show us objects turned into active subjects seeking a response from the viewer. The wispy drawings re-present as present people the subjects of Norman Tindale who photographed imprisoned Aboriginals, but gave them only serial numbers rather than names. In this way Ah Kee replaces the familiar brightly-coloured paintings (that allow you to get lost in their trails) with work that asks you short, sharp penetrating questions.

Purchase one of Ah Kee’s surfboards and you’re not only going to be standing on a tribal shield, but on the other side you’ll have Ah Kee’s drawing of his own half face staring back at you, as if to question why you have turned him to the wall or the sea bottom. One side represents an indigenous identity, the other himself.

In the third and final part of the video work Ah Kee leaves a surf board wrapped in barbed wire on the Surfers Paradise shoreline, before hanging it from a tree like a dead carcass and shooting the hell out of it. The analogy to history is blatant, suggesting that he’s fighting a terrible complacency by being unafraid of making big bold statements.

This artist’s drawing at Deane is lively and very competent, yet for all its political and personal re-positioning, it doesn’t hold much emotional charge for me here in New Zealand. Equally I find the more layered text works like Myth Understanding and the work in Roundabout adopting a rather tired ‘80s structure of building a textural body through the mechanized repetitive chant of words.

Ah Kee’s work generally I suggest can seem flatter and more polemic placed in a New Zealand gallery context. You can imagine these works zing in an Australian museum or Bondi surf store. Perhaps such factors help explain why we see so little fresh contemporary Aboriginal Australian work. Strenuously avoiding cultural clichés and working intelligently to reposition identity, Vernon Ah Kee’s practice remains of much interest and worth watching.

Mark Amery

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.