John Hurrell – 12 January, 2011

These paintings can be contemplated in groups, like the separate words that collectively and syntactically make up the meaning of a sentence. The reoccurring Frizzells provide subject-continuity while the ‘blank' unmade Apples chop the ‘text' up into separated clauses, so that the frieze becomes a piece of prose, a paragraph of ‘sentences', that is waiting to be ‘translated.'

Auckland

Christmas group show involving five Auckland dealers

Frieze

1 December 2010 - 29 January 2011

This unusual painting exhibition uses standard stretcher modules that are supplied to the participating artists - all linked to Gow Langsford, John Leech, Sue Crockford, Bath St or Antoinette Godkin - the widths created by measuring the gallery wall lengths and dividing them up. These uniform units can thus be squeezed in tightly, butted together to make up a continuous frieze - apart from the front windows and two doorways. Three sets of proportions are involved: 750 x 1500 mm, 750 x 840 mm and 750 mm x 750 mm.

Seventeen artists are involved: John Walsh, Dick Frizzell, Peter James Smith, Richard McWhannell, Michael Hight, Andre Hemer, James Cousins, Justin Boroughs, Billy Apple, John Pule, Sara Hughes, Denys Watkins, Miranda Parkes, Peter Gibson Smith, Chris Heaphy, Karl Maughan and Charlotte Graham.

The lion’s share, as you’d expect, come from Gow Langsford and John Leech. Most have one work, six have two, Billy Apple can be commissioned to make three, and Dick Frizzell has completed five.

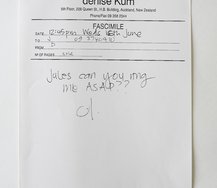

The amusing thing is that the line is not actually complete because Apple’s work requires negotiation and conversation (price and subject matter) to get started. His unpainted stretchers lean against the wall, resting on chocks, and above them a brief invitation to possible purchasers is written in place of the finished product. There is an aspiration that the finished work would still be exhibited within the show’s timeframe.

So, what of the positioning of works within this linear horizontal hang? How are artists juxtaposed, for there a great diversity of style? It is a key question because such placements are fraught with delicate social and aesthetic politics. You could resolve it with rolls of a dice or the drawing of straws - let chance create adjacent neighbours - but a lot of artists would not be happy with that. They would find it too frivolous.

For these reasons the gallery staff - in discussion with the artists - have done the positioning. Ideally the sequence can be seen as a sort of disparate comic strip to be read from left to right, moving clockwise round the room. Or the components can be scrutinised one at a time, in attempted mental (and optical) isolation. Or they can be contemplated in groups, like the separate words that collectively and syntactically make up the meaning of a sentence. The reoccurring Frizzells provide subject-continuity while the ‘blank’ unmade Apples chop the ‘text’ up into separated clauses, so that the frieze becomes a piece of prose, a paragraph of ‘sentences’, that is waiting to be ‘translated.’

Most people I imagine will see the works in discrete units, and have certain works they really relate to alongside others they don’t.

There are seven works here that really stand out. On the lefthand wall (facing in from the street), are paintings by Peter James Smith, Richard McWhannell and James Cousins.

Cousins’ contribution is a hovering, flat grey-brown cloud behind which are a set of varied marks partially exposed and running up to the edges of the horizontal, rectangular stretcher. These include liquidly flowing brushed on loops butted against solid colour that has been masked with intricate hatchings of parallel lines - varied fields of applied mark-making all peeking out from around the streaky misty centre. The work seems to allude to Laurent Grasso’s video in Auckland Art Gallery’s 2007 show Mystic Truths of an enigmatic cloudbank creeping slowly down at Parisian Street.

Peter James Smith’s painted panel with cut-out shapes and blobbily ambiguous objects plays with a child’s game of coordinating motor skills and recognition of negative ‘doubles’. Its title Rocks in the Sky references McCahon’s series from the seventies, whilst the images are reminiscent of Magritte and the collaborative conceptual paintings of Madeline Gins and Shusaku Arakawa on ‘the mechanism of meaning’ - but more painterly and traditionally seductive.

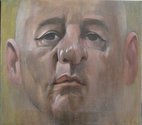

Richard McWhannell has a self portrait next to the Peter James Smith painting. It is a courageously imaginative depiction of the artist reaching his second childhood: a balding moonfaced visage, eyes glazed in lack of comprehension, nose pressed against the incubator glass. McWhannell’s physiognomy is set within a subtly distorting grid structure established by a discreet shawl or blanket pattern that suggests vulnerability and the need to be well wrapped up for protection.

On the opposite wall the Chris Heaphy painting Te Mangoroa (The Milky Way) has a golden backdrop over which is placed an intricate tracery in which are held scattered shapes and motifs from cartoons and illustrations. As items suspended like fish caught in a wide net of (uncoloured) negative shapes hauled up on a beach, these diminutive icons are cut-out signs that speak of almost forgotten narratives, small body parts serving perhaps as mnemonic aids for half remembered episodes in television animation.

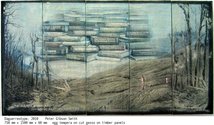

Peter Gibson Smith’s blending of painting, collage and photography (to make a daguerreotype) shows the ash covered slopes of Mt. Tawawera and - hovering in the background - ghostly stacks of the history books about to be written but which here seem portentous after the fact. The image heightens the unbridgeable separation between traumatic reality as experienced and any verbal account - the limitations of language, no matter how large the vocabulary.

The two works by Denys Watkins at opposite ends of the wall show his characteristically nuanced placement of shape, the caressing delicacy of his paint application and a shrewd choice of soft hues. The paintings gently pull against the picture plane, the Three Spheres of Joy being (for Watkins) chromatically assertive and strident in space, and Vibutron more filmy, as if floating like jellyfish underwater.

This unusual group show is worth checking out. Its odd hanging format is intriguing and creative peaks distinctly memorable.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.