John Hurrell – 21 July, 2012

One works with fields of runny liquid paint, capitalising on dribbles and intricate, barely detectable, stained-over pencil lines; the other utilising dry drawn marks scumbled or dragged over grainy textures. It seems to me that Pieters is from the holistic tradition of Olitski and Twombly; Akel from the manual and theatrical gestures of Bacon and Kitaj. A fascinating pairing.

Auckland

Kim Pieters and Anoushka Akel

Hop Scotch

Curated by Caterina Riva

13 July - 18 August 2012

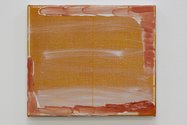

Two very different painters have their practices juxtaposed in this unusual (for Artspace) exhibition organised by Artspace director Caterina Riva. Dunedinite Kim Pieters is well known for her delicate oil-washed works on pieces of battered hardboard and has been working for almost thirty years. Surprisingly she is not widely known outside the South Island. Aucklander Anoushka Akel on the other hand is a recent Elam graduate who explores a repertoire of pastel and oil paint marks on small coarse-grained canvases.

One works with fields of runny liquid paint, capitalising on dribbles and intricate, barely detectable, stained-over pencil lines; the other utilising dry drawn marks scumbled or dragged over grainy textures. It seems to me that Pieters is from the holistic tradition of Olitski and Twombly; Akel from the manual and theatrical gestures of Bacon and Kitaj. A fascinating pairing.

With her oddly shaped rectangles of hardboard taken from demolition sites (with corners missing and oblongs cut into the side) that she butts together and hammers directly onto the wall, Pieters is brilliant at producing cascading veils of shimmering monochrome accompanied by inflections of contrasting hue that activate the stained and gouged field. With overtones of Australian artist John Olsen, she constructs on paper wispy dribbly landscapes, creating watery granular curtains and using thin pencil lines and ink doodles to lure the eye away from expanses of glowing void.

Though never precious, sometimes Pieters veers too close to it. Her fondness for clusters of diminutively drawn marks can become twee and mannered - overstating the delicate configurations needed to make a successful contrasting dynamic. Worse still, she often writes out the long evocative titles of her works along the bottom edge of her boards, vivid literary phrases that once read and comprehended, undermine her talent as an ‘abstract’ artist by setting up competing mental images that draw on narrative. This poetic (somewhat Gothik) language squashes the lyrical associations generated by her accomplished washes and drawing, goosestepping over them and enforcing its own replacement meaning. Perhaps if the paintings were a lot bigger and dealing with the sublime, or the titles were written on the back, the language might not seem so intrusive.

In contrast, Akel’s titles (all Three Handed Paintings) shun anything other than an intense scrutiny of her wobbly (or ruled) pastel lines, smeary daubs or dry-brushed wipes - positioned carefully on grainy sanded surfaces. Her intricate manual traces insist you focus on their presence on the canvas only - their stabbing bristle tics and flicks; the wristbased gestural dramas they imply. There is a suggested logic about some of her pellucid applications. A bit like Lasker (in the use of reason) though not in paint use - which is closer to Hodgkin.

It is their appealing rawness that makes Akel’s paintings the perfect foil for Pieters. Sometimes her canvases appear unfinished, being comparatively restrained and minimal. Their understatedness hovers closely to unstatedness, yet there is enough activity present to satisfy the needs of each ‘working’ stretcher. The speckled grain of her sanded background surface heightens the theatricality of the systematised linear additions which lie stacked in a closer different zone.

Pieters is about integration of fluid and line whereas Akel usually likes dramatic contrast and spatial layering - although several works show her skill with subtle tonal matching. Her overtly manual process with brush and pastel is much faster than Pieters’ methodology where the painted boards involve multiple slowly drying washes.

And though Hopscotch is a nifty title about a game there is little interaction between the two painters. They have a room each and share two. It is not like the Cousins Ingram show at Gow Langsford a few years ago. They haven’t responded to each other. There is no sense of two minds locking - though you can appreciate the cleverness of Riva’s curation.

This is an excellent show to visit and think about. Sadly if Pieters hadn’t discovered the pleasures of evocative language and coloured pencils it would be a swooningly brilliant one. Having said that, Aucklanders have never previously had the chance to see her wonderfully diaphanous yet pockmarked monochromes, so this show is a great opportunity.

John Hurrell

Recent Comments

Kim Pieters

John I agree the titles can complicate the work but that is fine by me. I have been using titles ...

John Hurrell

Hi Kim, thanks for those contributions. Twombly's use of language is integrated formally with the rest of the painting surface. ...

Kim Pieters

& this to finish... This end is not found immediately. At first stage, the title so to speak bars the ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 5 comments.

Comment

Kim Pieters, 11:41 a.m. 28 July, 2012 #

John thank you for your review. Apologies about my delayed response, I have been travelling south to the sun! I was most curious about your experience with my titles.

For me, the relationship between language and image is an important, if not exclusive aspect of my work, so your response was a little unfortunate; but perhaps one that I need to consider.

The titles never illustrate the image, they are never analogous, they are always supplement: evocative, often poetic, as you say, sentences, lines of language or quotes taken from their original context and relocated (very small I have to say, along the lower edge of my painting or drawing. They actually do not have to be engaged with and often they are not). However by making the placement I am presenting two autonomous moments, one literary and one visual. It is what happens at their junction which interests me a great deal. What may then come into being.

I am always looking for the generation of something new in that gap. Something that cannot entirely rely on what can be identified: the work is not a named representation, it has no end. The disjunction between language and image is purposeful; it can be a type of shock or intrigue. The space that is offered here, almost a type of clearing, asks for sensibility and thinking to be put into play. It is a call to the individual who pays attention, to generate meaning for themselves, from their own sensitivities and knowledges and in their own way.

The work in this perspective acts as an impetus, an initiator of moments. Of course I cannot answer for what is found, sometimes obviously it will be unpromising. I am happy to take that risk, for more often something else happens; something rich and sensate and thoughtful. This may provide discussion amongst friends; it could be an entirely private experience. It can be repeatable and ongoing, reconsidered, rethought, felt differently at different times, a bit like the things of life. It is a world.

May I refer you and anybody interested to the Hamish Clayton writing on my work in Art New Zealand’s autumn2011 edition. This is a close and considered reading which I like very much. I did not know Hamish when he wrote this and had no correspondence with him, so it is a reasonably unmediated response. There is also a beautiful discussion about titles by Roland Barthes in his ‘The Wisdom of Art’ essay on Cy Twombly of which I am entirely in sympathy with. Gosh, it is such elegant, informative writing I will quote the piece in full for you. All best Kim

well perhaps in a second comment...

Kim Pieters, 11:44 a.m. 28 July, 2012 #

Here is the beautiful Roland Barthes piece

“...The paintings functions like a pictograph, where figurative and graphic elements are combined. This system is very clear, and although it is quite exceptional in Twombly’s work, its very clarity refers us to the joint problems of figuration and signification. Although abstract painting (which bears an inaccurate name, as we know) has been in the making for a long time (since the later Cezanne, according to some people), each new artist endlessly debates the question again: in art, linguistic problems are never really settled, and language always turns back to reflect on itself. It is therefore never naive (in spite of the intimidation of culture, and above all of specialist culture) to ask oneself before a painting what it represents. Meaning sticks to man: even when he wants to create something against meaning or outside it, he ends up producing the very meaning of nonsense or non-meaning. It is all the more legitimate to tackle again and again the question of meaning, that it is precisely this question which prevents the universality of painting. If so many people (because of cultural differences) have the impression of “not understanding” a painting, it is because they want meaning and this painting (or so they think) does not give them any.

Twombly squarely tackles the problem, if only in this, that most of his paintings bear titles. By the very fact that they have a title, they proffer the bait of a meaning to mankind, which is thirsting for one. For in classical painting the caption of a picture (this thin line of words which runs at the bottom of the work and on which the visitors of a museum first hurl themselves) clearly expressed what the picture represented; analogy in the picture was reduplicated by analogy in the title: the signification was supposed to be exhaustive and the figuration exhausted. Now it is not possible, when one sees a painting by Twombly bearing a title, not to have the embryonic reflex of looking for analogy. The Italians? Sahara? Where are the Italians? Where is the Sahara? Let’s look for them. Of course, we find nothing. Or at least - and here begins Twombly’s art - what we find - namely the painting itself, the Event, in its splendor and enigmatic quality - is ambiguous: nothing “represents” the Italians, the Sahara, there is no analogical figure of these referents; and yet, we vaguely feel, there is nothing, in these paintings, which contradicts a certain natural idea of the Sahara, the Italians. In other words, the spectator has an intimation of another logic (his way of looking is beginning to operate transformations): although it is very obscure, the painting has a proper solution, what happens in it conforms to a telos, a certain end.

damn it is still too long. one more paragraph. worth it i think

Kim Pieters, 11:45 a.m. 28 July, 2012 #

& this to finish...

This end is not found immediately. At first stage, the title so to speak bars the access to the painting because by its precision, its intelligibility, its classicism (nothing strange or surrealist about it), it carries us on the analogical road, which very quickly turns out to be blocked. Twombly’s titles have the function of a maze having followed the idea which they suggest, we have to retrace our steps and start in another direction. Something remains, however, their ghosts which pervade the painting. They constitute the negative moment which is found in all initiations. This is art according to a rare formula, at once very intellectual and very sensitive, which constantly confronts negativity in the manner of those schools of mysticism called “apophatic” (negative) because they teach one to examine all that which is not-so as to perceive, in this absence, a faint light, flickering but also radiant because it does not lie....”

John Hurrell, 1:58 a.m. 29 July, 2012 #

Hi Kim, thanks for those contributions.

Twombly's use of language is integrated formally with the rest of the painting surface. His words (as cursively drawn language) and his painted marks are locked in the field together and can almost be interchangeable - whereas I think your words obstruct your visual imagery in the viewer's mind: they undermine its efficacy by competing. They intrude, and visually as formal statements through marks (to me anyway) are not sympathetic.

I appreciate what you are saying about the 'junction' as an aspiration, but think you are overloading the work. The painted washes are more than enough on their own.

Kim Pieters, 9:47 a.m. 31 July, 2012 #

John I agree the titles can complicate the work but that is fine by me. I have been using titles in this manner for the last 25 years. It is very much part of my practice.

The title is always supplement, almost separate, a thing to itself; most often abstract, open ended, poetic; all the better to act as 'satori' in relation to the visual image. Or easily, not to act at all.

Perhaps it is a matter of managing ones own measure, in order not to over saturate any experience. Or: well…. you win some, you lose some etc etc.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.