John Hurrell – 20 December, 2013

In McWhanneli's wideranging suite of Pierrot images we roam all over the globe, zigzagging back and forth in time, though mainly over the last 150 years. The communities and places he incongruously visits include Nez Perce, Tūhoe, Apache, Scott's expedition to the South Pole, British troops in Egypt during WW1, and the Harvey and Jeanette Crewe murder house. His images seem sparked off by photographs, and memories of paintings by artists he admires.

The figures of the Harlequin and the Clown are well known characters in the annals of pre-modernism and post-modernism, featuring for example in both the paintings of the young Picasso and the installations of Mike Kelley. One was maudlin and pitiful, the other (with its borrowed image by John Wayne Gacy) acerbically dismissive of the elevated achievements of the Enlightenment and human dignity. Both Harlequin and Clown (as Pierrot) come out the sixteenth century Italian theatre tradition of Commedia dell’arte: one a nimble black-masked trickster, the other a gawky, white-faced melancholic.

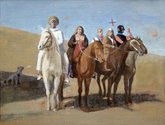

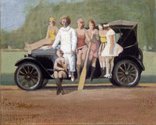

Along with a number of other assorted regulars, both feature heavily in Crossing the Lake, a suite of paintings by Richard McWhannell that is deeply conscious of certain European traditions but also vividly aware of Aotearoa as a place, a geography where location, community and history are inseparable. The nineteen oil paintings reference historic European painters (Courbet, Watteau, Vermeer) and some New Zealand ones (Moffitt, Fomison, Hammond, Earle) in subject matter and paint application methodology.

McWhannell, in temperament, has a fondness for the satirical and comically absurd, as evidenced by the two Balthus send-ups he presented in the recent Gus Fisher exhibition discussing pornography. (They were quite out of place.) In this Orexart show many of the works are digs at British imperialism, or unseemly parts of New Zealand (or other countries’) colonial history - based visually on old historic photographs and done in a style that mocks gently the dominant narrative.

McWhannell‘s Pierrot - modelled on Watteau‘s Gilles - is a figure of great naivety, an insensitive simpleton who also possesses more than a little vague self-comprehension. With his straw hat tilted up at the front, floppy ruffled collar, half mast trousers and pink shoelaces, this variety of self portrait doesn’t have the downcast gaze of Watteau’s original clown, but is more confident. Maybe stupider. He has a flair for turning up at various key historical moments, a conspicuous observer who, perceived as harmless, in times of conflict is left alone.

In some of the paintings we see a Harlequin figure representing the great Tūhoe religious and military leader, Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki. He seems to be wearing a mask, but his head, upraised arm and hovering attendant cross are derived from Te Kooti’s flag, his features based on the Archangel Michael (Mikaere), God’s warrior angel who appeared to Te Kooti in a vision.

In McWhanneli’s wideranging suite of Pierrot images we roam all over the globe, zigzagging back and forth in time, though mainly over the last 150 years. The communities and places he incongruously visits include Nez Perce, Tūhoe, Apache, Scott’s expedition to the South Pole, British troops in Egypt during WW1, and the Harvey and Jeanette Crewe murder house. His images seem sparked off by photographs, and memories of paintings by artists he admires - often when encountered in museums in Europe. The paintings here form groups where you can compare the odd dress of the participating protagonists, looking within themes such as rowing boat scenes, horse riding excursions, picnics in fields.

The odd thing is these images don’t really come across as corny, something you might reasonably expect with clowns. The reason is that they are sufficiently ambiguous to keep any precise meaning at bay, like any good surrealist work should. Probably the best example is The Performance Anxiety Dream. Pierrot’s pants have fallen down, he could be holding paintbrushes (but are they drumsticks? - he has no drum), and bird wings menacingly flutter around his head (but are they gesticulating gloved hands?). He is standing in the middle of an open field and he is vulnerable and distressed - for if he pulls up his pants he has to stop drumming. Perhaps it is about masturbation, or judging from the title, performance in bed. Perhaps the hands are female and reprimanding. It is an intriguing, compelling and very funny image, one of many in this unusual, beautifully put together, exhibition.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.