Andrew Paul Wood – 24 October, 2018

Mitchell père was responsible for a lot of early tourism and promotional art, including such iconic pieces as the Zealandia and the welcoming wahine for the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition of 1939/1940. The art is often all the more striking for the pure colours and simplified forms necessitated by the printing processes of the day. It was a period of furious national iconography-building.

Peter Alsop, Anna Reed, Richard Wolfe

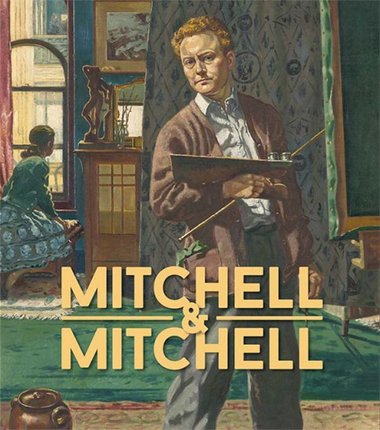

Mitchell & Mitchell: A Father and Son Legacy

Potton & Burton, 2018

There has, of late, been a growing interest in New Zealand’s rich legacy of commercial illustration. There is the touring exhibition Selling the Dream: Classic New Zealand Tourism Posters which launched at Canterbury Museum back in 2014. Christchurch Art Gallery currently has a lovely show of the work of Juliet Peter. This new book, Mitchell & Mitchell: A Father and Son Legacy, is a grand addition to the field, exploring the life and work of Leonard C. Mitchell (1901-1971), the father of New Zealand graphic design, and his son, Leonard V. Mitchell (1925-1980), winner of the inaugural Kelliher Art Award and the artist responsible for the huge allegorical mural Human Endeavour (1956) in Lower Hutt’s War Memorial Library.

One must, of course, grin and bear a certain amount of jingoism and quaint attitudes to Māori of the time, but there is some truly wonderful stuff here. Mitchell père was responsible for a lot of early tourism and promotional art, including such iconic pieces as the Zealandia and the welcoming wahine for the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition of 1939/1940. The art is often all the more striking for the pure colours and simplified forms necessitated by the printing processes of the day. It was a period of furious national iconography-building. Birds and plants were trotted out and dutifully scrutinised for possibilities in their stylisation, and, of course, Art Deco was ruthlessly assimilating Māori motifs into modernism long before Gordon Walters. It was every bit as sophisticated as anything that could be seen in Britain or the United States.

Mitchell fils (in the section rather excruciatingly titled “Painting Victor”) never quite found the commercial success of his father and eventually moved to the UK in 1959. He had altogether higher artistic ambitions, and although he could certainly match his father for technique, he lacked Leonard senior’s sense of composition, anatomy and decorum. Some of the works in his farewell exhibition before his UK departure—The Crucifixion, The Separation of Heaven and Earth (Rangi and Papatūānuku, and about as modernist as the romantic younger Mitchell ever chose to strive for) for example—aim high in concept, but remain pretentious failures in execution, and his portraits, though several were successful finalists for the Archibald Prize over the Tasman, occasionally threaten to dissolve into caricature. Another reason he no doubt wished to distance himself from Aotearoa is that with the identical names, his work was often confused with his father’s.

The junior Mitchell made most of his sales on the continent. While neo-romanticism in Britain lasted out the 1960s in certain select niches (as testified to by Pietro Annigoni’s portraits of Elizabeth II), Mitchell’s dark and saturated palette didn’t really suit the English rococo-esque taste for lighter, muted hues keyed to grey, and the younger generation were infatuated with op and pop art. The book is altogether kinder to his practice than it really needs to be.

Mitchell & Mitchell is a stunning book, worth acquiring as much for nostalgia value as art historical record.

Andrew Paul Wood

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.