John Hurrell – 22 November, 2018

Firstly much of this historic and contemporary work from over fifty photographers dwells on McLeavey's religious faith: An armless Jesus on an absent cross—placed on his bedroom wall—features in two wonderful images by Yvonne Todd, and most of the architectural photos he acquired feature ornate Spanish cathedrals, or adjacent arcades, some of them places he used to visit regularly.

Wellington

The international photography collection of Peter McLeavey

Still Looking: Peter McLeavey and the last photograph

Curated by Geoffrey Batchen and Deidra Sullivan

6 October - 20 December 2018

The chance to look closely at three-quarters (ninety works) of the personal photographic collection of Peter McLeavey is something not to be ignored. Amassed over a period of nearly thirty years this set of astonishingly diverse, purchased images tells us some things about the legendary dealer, taste-maker and cultural icon perhaps not obviously apparent to the many regular visitors of his gallery.

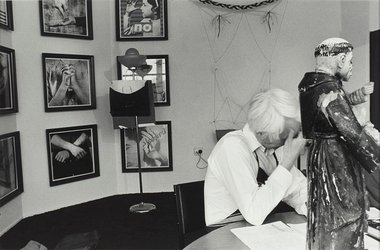

Firstly, much of this historic and contemporary work from over fifty photographers dwells on McLeavey’s religious faith: An armless Jesus on an absent cross—placed on his bedroom wall—features in two wonderful images by Yvonne Todd, and most of the architectural photos he acquired feature ornate Spanish cathedrals, or adjacent arcades, some of them places he used to visit regularly. Spiritual/theological issues embedded in Catholicism—such as death, afterlife, the Eucharist and contrition—are hinted at in many other images, especially the deeply disturbing (to most) photos he acquired of stitched up corpses or reclining body parts, taken by Joel Peter Witkin, or portraits of ‘Catholic-themed’ novelists like Graham Greene (by Bill Brandt) and James Joyce (Bernice Abbott).

These even permeate his purchasing of the occasional piece of avant-garde art, such as Sherrie Levine’s rephotographing and relithographing of reproductions of Edgar Degas works. Levine seems to ‘resurrect’ them by inserting them into twentieth century art, re-presenting them with an aura they might have once had—then lost. McLeavey also owned Joseph Beuy’s New Beginnings Are In The Offing, an offset lithograph that shows him comparing Greyfriar’s Bobby (a faithful Scottish terrier) unfavourably with an oil rig. Beuys was known to be inspired by the life of St. Ignatius Loyola, and the optimism of the title seems to have struck a chord.

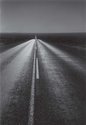

Then there is McLeavey’s profound love of landscape and history. Perhaps the latter explains why he collected photographs and not paintings, even though he spent most of his life championing some of the very best landscape painters this country has produced. Photography dwells on the transitory—the passing of time, slices of rise and decline, the emergence and disappearance of things—in a more intimate sense than painting. It has an inbuilt melancholy that painting lacks. It makes sense that he collected it. Especially works like James Nasmyth’s wrinkled Back of Hand and Shrivelled Apple (1874) or Francis Frith’s The Pyramids of Dahshoor from the East (1858).

This is a such a packed and wide-ranging exhibition, presenting so many important figures from the history of photography, that you need several visits. Peter’s love of New Zealand landscape is obvious (exemplified by works by Charles Clifford and Herbert Deveril), probably the result of his family moving around a lot, his father being employed by the railways. However it is the relatively new urban development that is striking here, especially when seen in the Wellington region, as is indicated by the photographs by George Henry Swan of buildings around Lambton Quay (1862).

Of course there are also the many portraits, the great images of McLeavey himself, taken by Yvonne Todd and Peter Black, and striking images of Māori by Elizabeth Pulman and Arthur Iles. One other even features the face of the moon, as in the Maurice Loewy and Pierre Henri Puiseux heliogravure (1898) that presents surprising detail.

This week, the late Peter Peryer is conspicuous by his absence; it is a surprise if McLeavey never acquired any work of his. There are four Aberharts.

With the photographs, we also see in vitrines samples of the correspondence McLeavey exchanged with his main source (Frish Brandt of Fraenkel Gallery), a couple of Fraenkel catalogues, and some of McLeavey’s journals with pasted-in personal photographs and notes. The published exhibition catalogue—with writing by Christina Barton, Peter Ireland, Geoffrey Batchen and Deidra Sullivan—is pretty good, though I would have preferred even more images and less text. For my taste, Batchen’s discussions of the artists and their historic context, though necessary, are a bit dry, and Peter Ireland’s contribution too short. In comparison the essay by Deidra Sullivan on McLeavey’s acquisition process and collecting ethos is perfect—a wonderful, thoroughly engrossing, informative read.

John Hurrell

![Dorothea Lange, The road west, New Mexico [U.S. No. 54, north of El Paso, Texas. One of the westward routes of the migrants], June 1938, gelatin silver photograph printed on warm-toned paper, Collection of Peter McLeavey.](/media/thumbs/uploads/2018_11/27_Dorothea_Lange_web_jpg_380x125_q85.jpg)

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.