John Hurrell – 6 July, 2019

We see engrossing footage of Max and his family on the beach, shots of shelled apartment blocks, overgrown gardens, military parades and brass bands, and groups of Russian tourists. We think about the status of nationhood, where does its confirmation come from? How do republics get locally and globally recognised?

Pakuranga

Eric Baudelaire, Evangeline Riddiford Graham; Emily Wardill

Wax Tablet

Curated by Andrew Kennedy

9 June - 11 August 2019

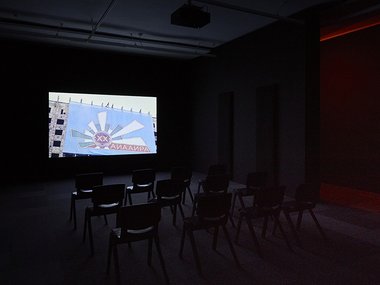

Two films, each over seventy minutes long, and one aural twenty minute ‘doco-interview’/installation, have been brought together by Te Tuhi’s exhibition designer, Andrew Kennedy, in a complex international show that looks intensely at memory, the agency of the human body and its (not necessarily assumed) attendant self, the nature of citizenship and the parameters of nationhood, and three individuals’ self esteem.

An uncommonly rich (but consistently and subtly creepy) show like this, being conspicuously ambitious and uncompromising, has buckets of gravitas with its chosen artists, and therefore high expectations of the time its audience will invest in their explorations. Several visits are presumed, for each of the three artists’ projects needs mental as well as physical space.

In other words, it would be ludicrously exhausting to attempt to see or hear all three in one go. You need time to consider them individuality, and then eventually to figure out how they work as a group. To speculate on the qualities that attracted Kennedy to these densely layered but seemingly disparate works.

Of the three, Eric Baudelaire‘s Letters to Max (2014) is the most interesting, for it presents information about recent turbulent events in Eastern Europe, a part of the world we in Aotearoa don’t hear much about; Emily Wardill’s When You Fall into a Trance (2013) the most seductive with its inventive distorting cinematography and twisted (psychoanalytical) narrative; and Evangeline Riddiford Graham’s Party Line (2019) the most shocking, especially for New Zealand women born after 1990, and who might not be aware of journalists Coney and Bunkle’s profound contribution to women’s (indeed all patients’—living and dead, male and female, old and young, born and unborn) rights in the face of intimidating and arrogant medical research.

Eric Baudelaire attempts to send 74 posted letters through the French postal system to the little known republic of Abkhazia and its ex-Minister of Foreign Affairs (02/10 - 10/11), his friend Maxim Gvinjia. We hear Max’s aurally recorded replies, and see videos of his daily life in a (now badly damaged) country which, with Russian help, broke away from Georgia after intense fighting and horrific atrocities. Although 103 minutes long, Gvinjia’s charm holds you in your seat, though you do wonder, how could this conflict ever be justified? What does Baudelaire think about all this? Are there things Max is not telling us?

We see engrossing footage of Max and his family on the beach, shots of shelled apartment blocks, overgrown gardens, military parades and brass bands, and groups of Russian tourists. We think about the status of nationhood, where does its confirmation come from? How do republics get locally and globally recognised?

The central figure in the second film, Emily Wardill’s When You Fall into a Trance, is Dominique, a neurotic and insecure neuroscientist trying to help a patient (Simon) suffering from loss of proprioception (a theme Wardill returns to later in her career), the ability to spatially estimate one’s bodily location and limb position without using sight. She has a daughter, Toni, an obsessive synchronised swimmer, and a none-too-subtle obnoxious boyfriend, Hugo, who claims to be an American agent that is posing as an aid worker. Hugo appears to be a bit of a stalker—a bully and a predator—one who also seems to have designs on Toni.

Mixed in with the intense conversations between these main characters are wonderful shots of synchronised swimming couples (sometimes upside down) looping and twisting in a blue watered pool, views of bubbling brown mud when Dominque and Hugo are walking through a sewerage plant, and distorted clips of naked rubbery limbs merging and inflating (like Andre Kertesz‘ balloon-like nudes) when Dominique and Hugo are having sex.

Evangeline Riddiford Graham‘s Party Line installation, as the title suggests, references a ‘community’ of six dangling pale telephone receivers. Through them, gallery visitors can hear a constructed interview with an anonymous woman doctor, based on the Metro article mentioned earlier written by Sandra Coney and Phillida Bunkle, exposing the cervical cancer experiments led by Associate Professor Herbert Green on unaware women patients in National Women’s Hospital Auckland (in hospital for other ailments), some of whom died through neglect.

Bunkle and Coney’s research led to the Cartwright Inquiry and that led to profound changes in hospital procedures for patients, and a much greater institutional sensitivity to ethical, emotional and legal issues revolving around gender politics.

A show like this is exasperating if you don’t live in Pakuranga, because the works (particularly Wardill’s) need several run-throughs, so you can sort out all the nuanced connections embedded in the dialogue, brace yourself for the gruesome bits (did I hear that right?) and follow up on backstories.

Visually I found Baudelaire’s film the most affecting, as it seemed like a mixture of Chantal Akerman‘s remarkable From the East and film footage of Christchurch after the big earthquake. Pretty grim. I liked it aurally, whereas I found Wardill’s male (narrative) voiceover pompous and irritating. And Riddiford Graham is used to working with brilliant actors anyway, as her fabulous work with Juliet Carpenter shows.

This is a tough unsettling exhibition. All the works are such. They all examine the nature of control and powerlessness, are very smart, at times deeply disturbing and often hard to like. At a time when northern hemisphere artists are rarely presented in Auckland, a big bouquet of flowers for Andrew Kennedy and Te Tuhi.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.