John Hurrell – 4 January, 2020

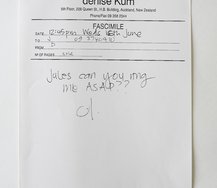

The notebook facsimile emphasises Lye's insatiable curiosity and how for four years he used sources such as New Zealand's Dominion and Auckland Museums for tribal carving images and Sydney's Mitchell Library for anthropological texts, to educate himself before he left for London as a stoker on a steam ship in 1926. It is a wonderfully fascinating document, with the copied sections of A.A. Brill's 1918 translation of Freud's 'Totem and Taboo' being of particular interest. Even though Lye later rejected them.

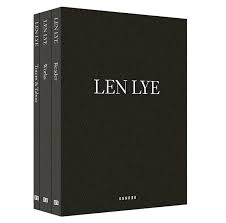

Len Lye—Motion Composer

Three volume set: Works [illustrations of]; Texts [ten short essays]; Totem & Taboo sketchbook [notebook facsimile]

A publication that accompanies the current Lye survey in Switzerland.

Exhibition curator and publication editor: Andres Pardey

Writers: Roland Wetzel (foreword), Andres Pardey, Paul Brobbel, Ann Stephen, Megan Tamati-Quennell, Scott Anthony, Tyler Cann, Barry Schwabsky, Wystan Curnow, Janine Randerson, Roger Horrocks

Design: Claudiabasel—Nevin Goetschmann, Jiri Opiatek

English and German versions

Museum Tinguely, Basel / Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg, Berlin, 2019

This elegantly designed set of three black books is part of a new survey at the Tinguely Museum (in Basel) geared to introduce Len Lye’s films, photograms, paintings, drawings, writings and kinetic sculpture to a European (especially Swiss and German) audience—an expansion of the Pompidou show he had in 2000.

The three volumes are organised so that an introductory elucidation from Roger Horrocks accompanies the museum drawings and hand-copied Freud and Gaudier-Brzeska entries in one volume (a 108pp facsimile of his first notebook), with nine other writers on assorted themes in a (158pp) second, and a selection of important images—including some of Lye’s own published writings—in a (210pp) third. It works well, especially as the texts are accompanied by little thumbnails that with page numbers are enlarged in the ‘image’ volume. For Lye enthusiasts this carefully prepared, beautifully designed, suite of interconnected books—that with their black covers and thin paper look like Bibles or concordances—is utterly glorious.

The notebook facsimile emphasises Lye’s insatiable curiosity and how for four years he used sources such as New Zealand’s Dominion and Auckland Museums for tribal carving images and Sydney’s Mitchell Library for anthropological texts, to educate himself before he left for London as a stoker on a steam ship in 1926. It is a wonderfully fascinating document, with the copied sections of A.A. Brill’s 1918 translation of Freud’s Totem and Taboo being of particular interest. Even though Lye later rejected them.

In its open-page spreads, assorted portions of Freud (four difficult essays that parallel the ‘primitive’ mind with contemporary neurosis and various universal prohibitions discussed by Frazer in The Golden Bough) and Gaudier-Brzeska’s texts are placed on the righthand side while noted observations and museum ink drawings (usually of tribal carvings) are on the left. Later on in his career, Lye lightly crossed out in pencil a large number of quoted sections he did not find directly useful.

With the book of essays, many of the contributors were participants in a symposium held in Basel in October. About half the texts directly shed light on aspects of the Totem and Taboo notebook (Horrocks, Tamati-Quennell, Pardey, Brobbel, Stephen, Schwabsky) and its relevance for works like the pioneering 1929 film Tusalava—though the topics they cover are generally far wider.

All the writing is clear and very informative. Horrocks and Curnow of course have been writing about Lye’s life and art for decades, and have set a very high standard, but the other contributors all provide plenty of unexpected new and interconnected insights. It’s a richly packed—very stimulating—anthology.

Pardey’s title for the survey, Motion Composer, is spot on and exactly as Lye would have wished; (echoed also in Roger Horrocks’ 2009 book on Lye’s films and sculptures: The Art That Moves). Amongst his selection of works for Switzerland, Pardey includes two of the last group of thirteen large paintings made in New York (at the end of Lye’s life) based on much earlier faded batiks or small watercolours, a puzzling move as they (in my view anyway) lack the tactility and sensitive surface of the ‘doodles’, and generally don’t translate at all well as glossy acrylic marks on canvas hangings. (I think only one work succeeded: the Aborigine influenced Family Conference.)

Barry Schwabsky is a much admired critic commonly found in Artforum, Flash Art, Art in America and LRB. His comments on these late works are particularly interesting because he looks at the image-making process—as opposed to surface patina (the aspect I personally find disastrous)—and why Lye insisted on enlarging images that were forty years old; and using another painting method. He sees Lye as assuming (as with his kinetic sculpture) that for painting: ‘It’s mostly the bigger the better (p. 93).’ However, I think Lye over-reached himself with scale and lack of intricacy in mark-making. I’ve always wondered why he got it so wrong. Even though he was getting ill and growing weak.

In his ‘Endless Summa’ contribution, Schwabsky explains that he sees Lye as one who linked his paintings with his kinetic sculptures in that the image was never meant to be fixed or static, but ‘always subject to reiteration and reinterpretation (p. 92).’ Even though Lye had slides made of his earlier doodles that he then projected onto his large sheets of canvas on which he drew in charcoal, he still had room for improvisation, be that colour choice, linear form or texture. The early work was not a rigid template, but a generating opportunity for play (Schwabsky looks at Roger Caillois’ approach to this).

The problem is that Lye was always tinkering with his projects (be they written elucidations or proposed artworks) so that they were ongoing and in a constant state of modification. It was typical Lye behaviour. And he himself apparently did not worry about the last suite of paintings—and was confident of their quality right up to the end—provisional though they might be. At one point Schwabsky mentions Tony Conrad, who made paintings that changed colour over time (as did Sigmar Polke) like a long-running projected film, but he is thinking of Lye’s paintings in a different sense. They are paintings that rely on the artist’s body to over time keep up the process of transmutation.

Schwabsky though—clever and (I think) too generous a writer that he is—does indicate there may be some grounds for misgiving. Although he writes of Lye creating ‘an art in process, an art which does not have a fixed form (p. 92)’, he appreciates also that there are issues with Lye’s ‘seemingly hasty, flat and inexpressive quality of the paint handling (p. 96),’ though he claims ‘It was a deliberate aesthetic choice (p. 96).’

I’m not convinced. I think that as Schwabsky notes, Lye was anxious about starting a new series of paintings, quite understandably worrying about ‘coming around to paint [them] after so many years in which he had not handled a brush (p. 94)’—but that he ran out of time to fix the problems.

In his fascinating detailed over-view of the major innovations that Lye initiated in film and sculpture, Wystan Curnow also looks at his crossing over of media boundaries, pointing out how this experimental methodology can be filtered through Jacques Rancière’s expression Distribution of the Sensible. When Lye’s strips of film become a support for painting with carefully added soundtracks, colour becomes so bodily it seems to ‘synaestheticise’ into sound; and likewise movement empathetically kicks into the viewer’s impulse to dance. So too with Lye’s ‘tangible motion’ machines which go far beyond the limitations of conventional sculpture to mimic the effects of light and movement in film, especially his own films like Free Radicals.

Curnow’s text is a brilliant, fresh piece of writing that ties in earlier astute observations about Lye by Malcolm LeGrice, Jean-Michel Bouhours and Evan Webb with the broader philosophical theorising of Rancière. It is one of many enjoyable articulated meditations on Lye’s achievements found in this terrific new publication.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.