John Hurrell – 3 March, 2021

Galloway's useful exposition spirals and criss-crosses like a twisting lemniscate around two well known discussions: Brian O'Doherty's critique' Inside the White Cube', and Dave Hickey's provocative essay, 'Frivolity and Unction'. One looks at the white walls of gallery architecture, the modernist interior being an earnest ‘spiritual' space that provides a contextual gravitas that opposes laughter; the other sees contemporary art as being an activity preoccupied with good intent that passed on to the visitor.

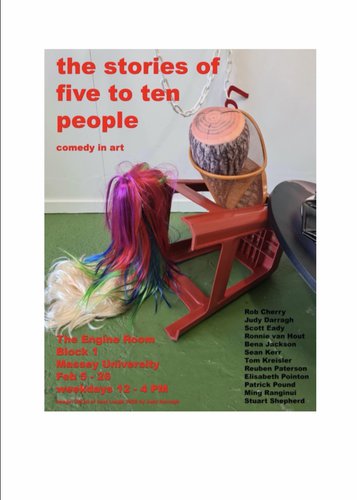

the stories of five to ten people: comedy in art

Edited (with an essay for this curated show of 12 artists) by Bryce Galloway

15 pp brochure, with some b/w and coloured images

The Engine Room (Massey University) Wellington, February 2021

As discussed in Bryce Galloway’s essay for this Engine Room show he curated, humour in the contemporary art history of Aotearoa has long been thought lacking, especially from the mid-sixties to the mid-eighties, due to the dominant influence of tonally dark ‘spiritual’ painters like Colin McCahon, Ralph Hotere and Tony Fomison. A serious earnestness prevailed.

However that picture presents an exaggeration. There is laughter to be found in McCahon’s paradoxical trbute, Here I give thanks to Mondrian (with its emphasis on diagonals), Hotere’s caustically witty This is a Black Union, Jack, and Fomison’s satirical ‘proboscis’ drawings published in Canta. It is not—even in that era—totally invisible.

So let’s not over simplify—though a tendency towards puritanism is clearly apparent. And bringing things to the present era, apart from the artists on Galloway’s exhibition list, there could also for example be Maree Horner, Dick Frizzell, Natasha Matila-Smith, Peter Robinson, Tony de Lautour, Marie Shannon, Wayne Youle, Ava Seymour, Paul Cullen and Kushana Bush. There are plenty of others too.

Galloway‘s useful exposition—a reworking of the No Laughing Matter: Contemporary art vs Humour paper he gave for the 2021 Australasian Humour Studies conference—spirals and criss-crosses like a twisting lemniscate around two well known discussions: Brian O’Doherty’s critique Inside the White Cube, and Dave Hickey’s entertaining essay, Frivolity and Unction (best found in his anthology Air Guitar). One looks at the white walls of gallery architecture, the modernist interior being an earnest ‘purified’ space (separate from ‘real life’) that provides a contextual gravitas that opposes laughter (seen as vulgar in itself); the other sees contemporary art as being an activity preoccupied with good intent that is passed on to the visitor. They benefit from the art experience but no mirth is involved. Their character improves but convulsive fun is not allowed.

Galloway points to a quote from Henri Bergson once mentioned by Simon Critchley: ‘Laughter (on the other hand) must answer to certain requirements of life in common.’ Yet I think it is a mistake to restrict laughter this way, as if it functions only outside of white cube purity. Humour or wit (non-slapstick forms of comedy) because they are ideational can be seen as variations of conceptual art (whether the punchlines are easily remembered or not). White walls may assist in bodily perception of a work’s formal attributes but they have no effect on logic—the core base that even when reversed underpins comedy’s linguistic structure. Room décor has no impact on viewer comprehension of verbal wit, nor btw the market, as any overseas exhibition of David Shrigley, Ed Ruscha or William Wegman paintings will show. It is so obvious I’m puzzled why Galloway bothered going down that road.

As for goodness (referred to by Hickey) or attendant piety (see Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe’s discussion of civic minded abstraction), that is often assumed in Aotearoa—and elsewhere—to be the driving motivation behind contemporary art production (an activity commonly regarded as ethics-based); a phenomenon that here seems to be encouraged by universities, and civic or government agencies.

Hickey obviously loathes the idea of art with a ‘worthy’ social agenda gaining too much traction. He finishes his essay by fuming over those who assume art has ‘preordained virtue,’ and advocating the merits for artists of ‘bad acting’ and ‘wrong thinking.’

Another related essay from him in Air Guitar, Pontormo’s Rainbow, ridicules high-minded pedagogocal psychologists of the early fifties questioning children about their responses to animated cartoons—the violent actions and chaos—fearful that they might be corrupted; and expecting ‘correct’ socially approved answers that ignore the ironic humour or visceral pleasures of frenetic movement and saturated colour.

In our own time, and here, there is currently an over-riding timidity in Aotearoa’s art community that is fearful of such ‘irresponsible’ frivolous attitudes, and so we are beholden to Galloway for raising these topics, spotlighting the surfeit of earnestness for our attention. Of course he is not the first person to do so, and six years ago critic Wystan Curnow was seen discussing this theme in Tom Who?, Shirley Horrock’s film on Tom Kreisler.

Nevertheless by raising the subject once more, Galloway is doing us all a big favour in the current political climate that can be seen as miserablist and dour, with its dominant emphasis on post-colonial activism, sociai change, the pandemic and eco catastrophe—and lack of variety in mood. However art modes should go beyond using the worthy as a template. They should also be varied and unpredictable and generating new modes of thinking; responding to fresh approaches to making, encroaching into previously unexamined mental zones. Encouraging heightened levity and kicking against the limits of logic (ostensibly found in the structures of language) through art furthers that.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.