John Hurrell – 10 April, 2024

If visitors were to be ‘just looking', what would that be—considering the loaded implications of the word ‘just'? Seeing but not analysing? Viewing while being aware of surrounding space only, oblivious of penetrative details, only outer surfaces that are peripheral? Or only aware of a vague distant wall directly in front—with things arranged on it? And logic, maybe, is involved.

Just looking? Not in your life. I think Pound, with his cursory title, actually expects us to search for meaning too in this show, with a piercing scrutiny—though he is not saying. That these contrived enigmas (being art), using juxtaposed intact found photographs that might have a connection, are really devised to embolden and then tantalise and perhaps exasperate mentally adventurous gallerygoers—but not too much. They are designed to be visual bait that initially attracts tentative nibbles of interpretive speculation and then sneakily lures bigger bites that involve more complex thinking.

If visitors were to be ‘just looking’, what would that be—considering the loaded implications of the word ‘just’? Seeing but not analysing? Viewing while being aware of surrounding space only, oblivious of penetrative details, only outer surfaces that are peripheral? Or only aware of a vague distant wall directly in front—with things arranged on it? And logic, maybe, is involved.

These arranged things prompt Pound in his printed statement to be enthusiastic about ‘looking’, as opposed to ‘just looking’. Yet if one happens to be captivated by art as a solvable enigma (the type of viewer he wishes to attract) then ‘looking’ itself means an investigation of the presented images. Even if (as he states) that person knows it is a ‘folly’.

The direction of the photographed subject’s ocular interest is one investigable component.

The vectorial direction of photographed bodies in mid-air is another.

Or the back of heads, of people looking away from the camera. They are gazing at walls covered with the blank numbered backs of other photographs which of course hide their images. About these they might speculate. Of the centrally positioned back-of-heads we do see, the necks and shoulders are included to stabilise. The hairstyles (the verso part) are deliciously ornate, as are the suits, and patterned walls they are focussed on.

Flat planar containers bearing text is one more curiosity (these lids serve as frames that declare themselves to be containing puzzles). Or incorporated parts of games involving language and its letters (they serve as plinths).

Two micro-installations include Scrabble racks that pun on the content of the seated image. Here (as with the boxes) Pound I think is being too complicated, trying too hard by self-consciously injecting unsubtle ‘clues’ into his work. His nudging of the viewer is blatant.

Despite this the two tiny cut-out Double Portraits are intriguing, playing off ‘looking through’ against ‘looking at,’ pushing exposed body form or found cursive text against the inner edges of silhouette. These collages work terrifically by themselves. They don’t need additional theatricality.

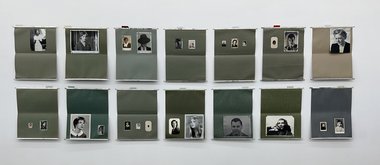

Storage folders (‘swing files’) located permanently in the metal drawers of cabinets are also unusual elements that Pound has connected to images. They blend with them—so that the folders ‘telescope’ contextually into the architectural properties of the artist’s studio or office—dissolving through narrative any separation between artist, their processes and the discovered artefact. These works (Looking Up, Looking Down) fetishise not the materiality of the depicted image or its surface but the artist’s contextualising history of accumulation—where stuff is kept—yet the viewer has to assume that these newly energised exhibited aspects, that shine a light on working method, are not calculated fictions but grounded in authenticity.

Gallery visitors are invited to zero in on Pound‘s combinations of found photographic image, but the anticipated ordering logic connecting elements within single works is sometimes extremely opaque. Disappointingly so if you expected Pound to always present rationality. Great if you think he is extolling (as in the case of On the Telephone) the pleasures of memory and a personal history of movie going.

Size is an important element too. Some portrait images are very old and tiny, particularly those on the fourteen swing files. A few are oval in shape, not square—and on two occasions, the last in a rare series of three in sequential juxtaposition. In contrast the biggest work here takes up a whole wall, the mentioned On the Telephone (with eighty film stills) a homage to Christian Marclay’s legendary 1995 montage film Telephones, with its sections from 130 movies.

It is a subtly provocative show, for instead of just looking, could one—like those people facing blank photograph backs—be better engaged in ‘just not-looking’, or ‘just not ignoring’ either, just mentally ‘attending’ in a tangential fashion; because despite the props there is usually an initial stimulus that is more than enough—without nonchalantly gazing in a fruitless direction, just scrutinising everything but?

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.