John Hurrell – 7 July, 2009

What is this thing called ‘art practice' and how does it fit in to the requirements of a university?

Wellington

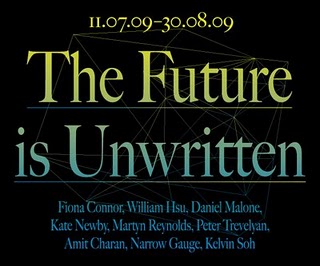

Curated by Laura Preston

The Future is Unwritten

11 July - 30 August 2009

Over the last few years one of the subjects increasingly brought under close scrutiny by writers such as James Elkins is that of the relationship between academia and art, especially within the structure of a PhD study programme. What is this thing called ‘art practice’ and how does it fit in to the requirements of a university. More particularly, what is ‘research’? Should I say ‘Research’ (with a capital R) for doctorates? Is that word accurate for what artists (post-graduate or otherwise) do? In a studio or out of it. Does it correlate with Research carried out by those in other disciplines, with its necessary (and copious) reading and writing?

Now the following discussion is not a review. It is a speculative pre-amble (my ‘Cohen’ to Laura Preston’s ‘Strummer’) that appears two days before this Adam exhibition opens. I’ve been invited by the curator to post some comments in advance. It’s an interesting idea for a number of reasons, one of them being the relevance of the above paragraph. She is interested in guest artists doing interdisciplinary ‘research’ within Victoria university, and has sent me a gallery invite containing a mini-essay and various background bits and pieces. Preston’s essay is more detailed and more interesting than what you get on the gallery website.

Click on the Press Release here and you will get a somewhat simplified version of what she is up to. The project involves turning the Adam Gallery into a sort of research centre for ‘critically thinking’ conceptual artists that mostly inhabit the thread that runs from Art and Language to Thomas Hirschhorn. Its curatorial ethos appears to be based in part on Charles Esche’s discussion of A Modest Proposal, and partially on the ideas of Simon Sheikh, and it briefly looks at Jacques Rancière’s espousal of a certain kind of critical art that experiments with form (see March 2007 Artforum), or structure as reflected in Paola Virno’s analysis of jokes. The antecedents of the interdisciplinary curatorial emphasis are easy to find. Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Laboratorium, and several decades earlier the late Billy Kluver’s E.A.T. projects with Rauschenberg and others.

All with the aim of acknowledging the current time of crisis (G.F.C. and ecological) and using the university as “a place for interdisciplinary thinking” for achieving “a critical analysis of the current climate.” So in this period of post-postmodernism, where irony is rejected and a belief in meaning re-asserted, the seven artists and two designers, through their conversations with the curator and other university staff, might (they are free to fail to produce) “shift the idea of what a ‘work’ constitutes and what it should deliver.”

Preston points out that Rancière believes that the political in art resides in the power of its form. His term “the distribution of the sensible” refers to the restricted divisions of place and forms of community participation that centre on apprehended modes of perception, not only what is visible or audible but also what is thought, said, made or done. He sees artistic practices as ‘ways of doing and making’ that intervene in this general distribution as well as in the relationships they maintain to modes of being and modes of visibility.The curator sees Rancière as placing value on “what is felt, (re-engaging with) art’s affect.”

In Artforum Rancière says “For me the fundamental question is to explore the possibility for play. To discover how to produce forms for the presentation of objects, from for the organisation of spaces, that thwart expectations. The main enemy of artistic creativity as well as of political creativity is consensus - that is, inscription within given roles, possibilities, competences.” (p.263)

When you look at his examples it is clear the playfulness is within certain forms of interventionist practice, within works that involve critical thinking. It is clearly not wildly fooling around for its own sake, but has a set out, contextualised political agenda.

In her search for empathetic practitioners I wonder though if Preston’s emphasis on ‘young artists’ in the Press Release (though Malone is not young) might severely hamper the success of this project. Older artists like Bruce Barber, Jim Allen, and Ralph Paine, university teachers (or retired ones) who know the politically intricate departmental infrastructures of such institutions well, might get greater use out of its interdisciplinary facilities. Their experience might achieve more conceptually exciting results, and draw out the rich possibilities of Victoria University as a pedagogical site.

That aside, Preston has an inspired range of artists here (who might consider themselves ‘critical thinkers’ though that can’t be assumed) that represent a wide variety of practice morphologies.

To speculate on the show one would have to speculate on the bodily experience of entering the Adam architecture to discover the location of each individual and the form of presentation each artist embraces, or the gallery websites, which I happen not to see as ‘dematerialized’. Such sensations are crucial to their content; the means they provide of access to their conceptual material.

In other words, though Preston considers these artists ‘conceptualists’ it is a word that nowadays has become meaningless through overuse and contradictory inclusions. Even early ‘conceptual artists’ like Kosuth or Sol Lewitt (Wittgensteinians or mystics, not necessarily Marxists) use sensuality and form as a carrot to draw their audiences in towards the ideas. They never abandon the aesthetic, the physicality of visual appeal. So with this show’s artists, whilst some may be enthusiastic readers of theory, that doesn’t mean the results of their research will be automatically interesting - visually in terms of concrete materiality experienced by the senses, or visually in terms of linguistic description experienced in the imagination.

However the nature of the research Preston is advocating here (what she calls ‘propositional’), some might argue is not really research at all. That the term is inappropriate when applied to most artists, even those thought ‘conceptual’.

Certainly the open-endedness of this socially hermetic project worries me. The lack of accountability and refusal to assess itself I see as irresponsible (I feel the same about Esche and Sheikh - see the latter’s “Constitutive Effects: the Techniques of The Curator”, in Curating Subjects ed. Paul O’Neill). Preston describes a win/win situation where the exhibition cannot fail. She doesn’t acknowledge any criteria through which she must evaluate the project, and allow for the possibility of its collapse - or that certain individuals cannot contribute effectively and she has misjudged them, or expected too much.

What of the role of the curator in her ‘conversations and collaborations’? I would hope that she not try to be an artist herself, that she is a facilitator, a nurturer, a provider of introductions and available means, but not a puppetmaster using the Adam as a theatre where the artists are manipulated by her. A ‘collaboration’ should not imply Preston is an artist. Here though, I think it does.

As a quick glance, it is easy to see why these nine individuals were picked: Amit Charan has a finely tuned, subtle mind, as indicated by his use of a videoed actor to recite with manual sign language definitions from some of Joseph Kosuth’s artworks, or his insertion of marginal codes, such as floral arrangements, into exhibitions; Fiona Connor is well known for her interest in subverting the physical properties of architecture - and the Adam is the prefect building for her to be set loose on; William Hsu has an established interest in science and various global environmental issues; Daniel Malone for his enthusiasm for Situationist practice and for Giorgio Agamben’s The Coming Community as indicated by the pamphlet Autonomous Anonymous: On Being Whatever that he co-wrote with Ralph Paine; Narrow Gauge is known for elegantly designed publications and posters; Kate Newby for her interest in fashion, the poetical properties of language (allusions to early conceptualists like Lawrence Weiner) and her ability to sculpturally intervene in unusual spaces; Martyn Reynolds has eloquently indicated his interest in the writings of theoreticians like Rancière and the practice of Jason Rhoades; Kelvin Soh is known for innovative commodity design, posters and comics; Peter Trevelyan has an interest in mathematics, dystopian devices and systems of surveillance.

Hopefully on Friday evening there will be a lot happening (or starting to happen) with the beginnings of various processual strategies in and around the Adam Art Gallery building, and online. Call or log in to follow the much anticipated, but as yet unarticulated, ‘unwritten’ developments.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.