John Hurrell – 20 August, 2010

In his reverie the repeated, babyfaced schoolboy always holds a pencil, and seems to represent a young Hurley, drawing. That pencil, besides supplying a narrative, is also a pun on pensive (three collages have implied thought balloons). And far fetched as it may seem - for these images are so wholesome - it may also be a pun on penis, for one image shows the same sad-eyed boy years later with a grey beard and holding a broken pencil, maybe a symbol for elderly impotence.

Baad/Good Grammar is an excellent title for this exhibition because it happens to crystallise what I think Hurley’s brand of oil painted images are all about. They have nothing to do with personality, character trait or individuality. In fact the ‘sitters’ or ‘original sources’ have zilch to do with their own physiognomies as exploited by the artist, for the works’ content is really about class, or status - expressed through codes for the various head or clothing parts. Thoroughly integrated into each body of course, but still highly stylised conventions and as such, glyphs; signs which with-hold nuance, restrain sensitivity.

That means there is no hint of mystery or hidden/private self here. Forget any notion of interiority. The templates alluded to by the stencil-like appearance are societal, the ‘stamped’ result determined by birth and privilege.

Such an image construction plays with formal properties like hard edged hair contours, or softly modelled face shapes. They come together in an uneasily discordant synthesis, like oddly matched syntactical components within a sentence. Hence the punning title, the ‘correctly’ expressed language of the subject and the peculiar formal visual language of Hurley.

So this show? Well there are three large, very typical, oil paintings (the best things here), some smaller oils, and a large number of collages that exploit different coloured or patterned papers. The latter feature painted-on paper portraits Hurley has cut out and added to, and some have stuck-on letters.

Five collages feature variations of a schoolboy daydreaming. They have a flat pure quality in their use of gouachelike colour - no modelling - much like portraits made by Alex Katz the American painter. This makes them look a bit sweet with their more saturated colour, for the printed chroma is more intense and less greyish than in the oils.

In his reverie the repeated, babyfaced schoolboy always holds a pencil, and seems to represent a young Hurley, drawing. That pencil, besides supplying a narrative, is also a pun on pensive (three collages have implied thought balloons - images near his head). And far fetched as it may seem - for these portraits are so wholesome - it may also be a pun on penis, for one image shows the same sad-eyed boy years later with a grey beard and holding a broken pencil, maybe a symbol for elderly impotence. Perhaps though, as Freud once said, sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

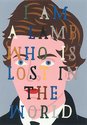

The works using letters I find awkward. The text “I am a lamb who is lost in the world” could be ironic or attempted humour - unless the subject is nineteenth century essayist Charles Lamb - but it comes across as maudlin. Hurley’s imagery overall, with his oil painting style seemingly derived from Leger and Stuart Davis, is not particularly interesting as contemporary or historical portraiture (it is so formal and stilted), but it is intriguing as odd spatial arrangements of almost floating, facial semaphores.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.