Warren Feeney – 21 April, 2011

Further claims about the artist's typography and design practice as challenging or ‘risky,' by a designer without formal graphic training who preferred to ‘trust his own artistic judgement' are equally questionable. The description of his art in the 1930s as an ‘alchemy of diverse influences,' is also not quite the remarkable alchemic polarity it claims to be.

Christchurch

Leo Bensemann

A Fantastic Art Venture

11 February - 15 May 2011

(This review’s posting was delayed in the hope that, after the big February earthquake, the Christchurch Art Gallery would open before the show’s scheduled closing date. As that is not going to happen, and as Warren’s review is of public interest anyway, I’ve decided to put it up. JH.)

Concealed within this comprehensive survey of drawings, paintings, prints and publications by Leo Bensemann is a great exhibition waiting to get out. As co-founder of the Caxton Press (1937) and designer of The Group’s exhibition catalogues (1940-1977), Leo Bensemann (1912-1986) was an influential figure in contemporary arts practice in Canterbury for over 30 years. However, Leo Bensemann: A Fantastic Art Venture, does what all retrospective exhibitions should and should not do, revealing anew a talented artist, yet over-representing weaker aspects of his practice. To its credit, the inventiveness of Bensemann’s art is evident in his work as designer and printmaker. Yet, the inclusion of numerous portraits and landscapes equally exposes the constraints of his practice as a regionalist painter.

Based on the mistaken premise that painting is at the top of a fine arts food-chain that always represents the very best of ideas, the attention that A Fantastic Art Venture gives to Bensemann’s paintings distracts from a closer consideration of the legacy of superb designs, drawings and prints.

And Bensemann was a skilful designer, with the best of his portraits persuasive because of their formalism. Laurence Baigent (1938) and Portrait of Mary Bensemann (1943) are highlights, with the Baigent portrait a lesson in elegant modern Art Deco style. In other portraits Bensemann’s figures seems too self-conscious, parading a public personas at the expense of an insight into more complex aspects of personality. Similarly, his landscapes adopt the style of hard-edged regionalism but reveal little genuine response to the landscape itself in the way that painters such as Rita Angus achieved. Bensemann’s works seems more about celebrating a way of painting, rather than the artist being an active participant in particular painting conventions.

A comprehensive and well-designed publication by Peter Simpson accompanies this exhibition and although impressive in its detail and documentation, it overstates the case for Bensemann as a talented, but artistic outsider. Claims that Bensemann‘s commitment to landscape painting in the 1960s occurred as younger painters embraced abstraction are contextualised as the decision of a ‘non-conformist who paid little attention to the ebb and flow of artistic fashion.’ However, with less than a handful of dealer galleries throughout the country and an arts community still largely unfamiliar with European abstraction, the best contemporary New Zealand art until the early 1970s was considered to be hard-edged landscapes and figure paintings by artists such as Don Binney, Robin White and, in Canterbury, Bensemann.

Further claims about the artist’s typography and design practice as challenging or ‘risky,’ by a designer without formal graphic training who preferred to ‘trust his own artistic judgement’ are equally questionable. The work for The Group and art publication Ascent (1968), reveal Bensemann’s mainstream position, responding to the influence of British Neo-Romanticism in the 1950s and Geometric Abstraction in the late 1960s. Similarly, the description of his art in the 1930s as an ‘alchemy of diverse influences,’ (balancing German folk tales with New Zealand’s modernism) is not quite the remarkable alchemic polarity it claims to be. Regionalism was an international art movement that embraced earlier historical/cultural traditions. What about Rita Angus’s Otago landscapes and medieval Japanese printmaking, Colin McCahon’s The Marys at the Tomb and Quattrocento painting, or Gordon Walters and Māori rock art? Like many of his contemporaries, Bensemann’s work also referenced indigenous art and culture.

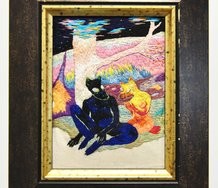

Certainly, the magic of this exhibition resides in Bensemann’s work with the Caxton Press and the section titled, Behind the Mask, encompassing The Group catalogue designs, prints and pen and ink drawings. There isn’t a series of illustrations comparable to Bensemann’s Fantastica, (1937) in New Zealand’s cultural history. These imaginative black and white Audrey Beardsley-inspired illustrations represent a curious and compelling response to Christopher Marlow’s Doctor Faustus while wood engravings such as Ball Dance (1949) or the pen and ink drawing Nastagio and the Obdurate Lady (1940), invite comparison with Nicola Jackson’s drawings and prints, but Bensemann’s imagery is supremely weirder.

A Fantastic Art Venture? The exhibition’s title seems almost a disclaimer, excusing Bensemann for the strange places that he sometimes took his paintings to, yet when considered in the light of his designs and prints it becomes the perfect phrase and adjective for an arts practice, deserving of the attention that this exhibition has sought to bring to it.

Warren Feeney

Recent Comments

Andrew Paul Wood

When I have time, one day I will write an article on what I suspect is the influence of fantasy ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

Andrew Paul Wood, 12:50 a.m. 9 May, 2011 #

When I have time, one day I will write an article on what I suspect is the influence of fantasy illustrators like Harry Clarke

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Clarke

Sidney Sime

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidney_Sime

and others.

Less Beardsley than the following generation.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.