Warren Feeney – 26 March, 2018

If Robinson's recent and previous selection of materials and occupation of a gallery space seemed more user-friendly, with things like bits of carpet, coloured felt, plastic straws and cardboard boxes, it might initially be assumed that the diminutive metallic objects in this current installation would be a more austere experience. Yet 'Fieldwork' has an intimacy to it that owes something to the scale of its objects and their seeming vulnerability in the expansive gallery spaces that they occupy.

There may not be an abundance of fencing wire in Peter Robinson‘s Fieldwork but, in a curiously particular way, its presence reverberates throughout both floors of Toi Moroki Centre of Contemporary Art’s gallery spaces—as well as its loading bay and toilets.

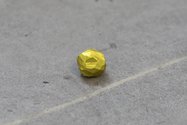

In Fieldwork Robinson again considers the potential of sculpture to inhabit and reside in a gallery space, as opposed to parading itself as testament to the ideologies and intentions of an artist’s practice. That’s part of the reason why Fieldwork looks like Robinson’s most subtle and lyrical exhibition to date. Consisting of 65 objects on CoCA’s first floor and 14 on its ground floor, the relationship between Robinson‘s objects and the Gallery’s architecture is near seamless, with the artist placing materials from his studio (bits of wire, nails, pins, staples or welding rods), in corners, on floors, in toilets and storage areas, its lift, exit corridor and spaces between galleries.

Certainly, it is near impossible to walk through Fieldwork without feeling as though you are out there with him, taking in all the necessary information, increasingly conscious of the lay of the land. In this sense there is a theoretical connection to the environmental art of the 1970s. but Robinson‘s terrain happens to be CoCA’s 1968 brutalist modernist building, previously known as the Canterbury Society of Arts gallery.

Designed by Minson, Henning-Hansen and Dines it opened 8 March 1968, so the scheduling of Fieldwork, opening in the first week of March 2018, is an appropriate way to acknowledge the building’s 50th anniversary. In fact, no exhibition in its history has so purposefully examined and discreetly directed the visitor’s attention to the nature of its gallery spaces, materials and the experience of its light. (Billy Apple’s studies for the realisation of three proposed works 1979 - 1981, in April 2000, is the most immediate and obvious comparison, but Fieldwork has a respect and affection in its response to its subject, whereas Apple’s was more critical.)

Yet it would be incorrect to reflect upon Fieldwork as exclusively directing its attention to CoCA’s building or history as the Canterbury Society of Arts. Rather, Fieldwork embodies a wider response to functional architecture from the post-war era, highlighting its masculine severity and asceticism. In reality, from its opening in 1968 until three years ago, Henning-Hansen and Dines’ building had vinyl flooring and carpet throughout, prior to its face-lift in 2015 and reopening in 2016. In the best spirit of ‘truth to materials’ the carpet and vinyl fit-out from 1968 were removed, exposing its concrete floors throughout. This reconsideration of its architecture means that in 2018, CoCA’s building represents the realisation of an imagined art history about the radicalism of modernism in 1960s Christchurch. In the same way, its current programme anchors its past almost exclusively in the ground-breaking nature of exhibitions like Women’s Environment in 1977, when the building was restricted to women only, seeking to ‘feminise’ its gallery spaces and its exhibition programme.

The 2015 make-over is a critical aspect of the experience of Fieldwork, as the exposed concrete floor—in its limitless shades of gray and its dominating materiality throughout the building—is central to its success. If Robinson‘s recent and previous selection of materials and occupation of a gallery space seemed more user-friendly, with things like bits of carpet, coloured felt, plastic straws and cardboard boxes, it might initially be assumed that the diminutive metallic objects in this current installation would be a more austere experience. Yet Fieldwork has an intimacy to it that owes something to the scale of its objects and their seeming vulnerability in the expansive gallery spaces that they occupy.

Most importantly, however, is the relationship that Robinson sets up for the gallery visitor as an interactive experience, inviting us to reconsider our association with its spaces, “with viewing, with framing, and with objects.” The placement of two large and expansive, free-standing wire grid lattices, suspended and appearing to float in the centre of the Mair Gallery, frame and position objects on the walls and floor as we move through the space, changing our experience of objects and their relationships with one another. These gridded lattices both align with and define the space of the Mair Gallery, giving order and certainty to the materiality of spiralling twists of wire and clusters of nails and pins on the walls and floors which—in the sparseness of their presence—direct our attention to the spaces in between.

It is a formalist encounter that Robinson has always been adept at, one centred upon principles of modernism that remain a constant in his work. The scattered orchestration of his subjects, and attention to the spaces they occupy and the objects themselves, were faultlessly represented in his series of untitled works on paper in 1999, and equally in the large black canvases from 1997, where the central location of subjects in white, were visually secured by a bold, upper-case text at the base of each painting.

There is a stillness and inescapable element of contemplation to Fieldwork that contrasts markedly with Robinson’s work next door in the Christchurch Art Gallery’s group show, Your Hotel Brain. Das Es, (2006), is a giant doughnut with an enormous phallic sausage reclining in its centre. The temperament and intention of Das Es and Fieldwork could not be further apart, yet both look and feel like significant works, the differences representing a measure of the scope and scrutiny that Robinson continually brings to his practice.

Indeed, as an artist whose work has frequently been described by its ability to shock or surprise—manoeuvring with chaos and intent across unchartered territory—Robinson’s art, when pleasurably encountered, has also been about recognising precedents, and being reminded of the surprising uniformity that makes up his practice. Fieldwork is among the best of such experiences.

Warren Feeney

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.