Warren Feeney – 11 January, 2018

Yet many of these paintings and objects no longer seem steeped in ‘bogan and bad-white art' attitudes. The provocation that they once represented to serious painting over twenty years ago is gone. It now comes as a surprise to witness tangible evidence of their faith in, for example, painting as a means of making an important statement or commentary on the human condition.

Christchurch

Group exhibition

Your Hotel Brain

Curated by Lara Strongman

13 May 2017 - 8 July 2018

Opening in May 2017 at the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, Your Hotel Brain is a group exhibition predominantly of works of art from its permanent collection that, even after eight months of return visits, remains both a frustrating and rewarding experience. The curatorial brief describes it as focussing on ‘the cohort of New Zealand artists who came to national - and in some cases international — prominence in the 1990s, many of whom had a particular association with Christchurch.’

Put together by senior curator, Lara Strongman, Your Hotel Brain confirms that a selection of great artworks does not always make for a great exhibition. More interestingly, it also shows that previous assumptions about a number of the participating artists’ work from an earlier period are now inappropriate or invalid.

In addition to the attention Strongman pays to the cohort of ‘usual suspects’ initially from Canterbury— Shane Cotton, Jason Greig, Bill Hammond, Tony de Lautour, Saskia Leek, Seraphine Pick, Peter Robinson, Grant Takle and Ronnie van Hout—Your Hotel Brain also looks like a belated beginner’s guide to Post-Modernism. Strongman states that it encompasses the work of artists who appropriate ‘lived experience—often through the lens of popular culture.’ From this perspective the exhibition is defensible as part of any public art gallery’s programme to educate general audiences, highlighting and illuminating a particular time-frame and context in the country’s art history. Yet, for regular gallery visitors and dedicated visual arts audiences, this is a taken-as-given curatorial premise; one that feels unnecessary—even patronising.

As such, Your Hotel Brain seems a little lazy in its assertions and selection of works. The exhibition generalises attitudes in contemporary arts practice from the 1990s and 2000s, without acknowledging that these two decades represent different and distinctly complex responses from one to the other, and that the 1980s initiated a period of productive activity for the decade that followed. Such an admission would have gone some way to respecting the differing levels of expectation and knowledge of audiences visiting the gallery.

Strongman describes the exhibition’s title, Your Hotel Brain, as ‘a metaphor both for the atomisation of history in the 1990s and the way that information is often detached from context in our contemporary digital age.’ It is a claim that needs to be qualified. Digital technology and its capacity to proliferate millions of images daily and globally may have fed the flames of appropriation in the 1990s, but its principles and practice were evident in the 1970s and early 80s, particularly in the feminist movement and the photographs of Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman, whose influence found expression in New Zealand in the work of Di Ffrench and Margaret Dawson, who is represented by two works in Your Hotel Brain.

Dawson’s fictional self-portrait, Marg n.l. Persona, 1987, is well-suited to the thematic concerns of the exhibition, yet it belongs to an art historical narrative that began with conceptual and performance art in the 70s, rather than the culture of the 1990s.

The inclusion of work by Julian Dashper’s Blue Circles #1 - #8, 2002 - 03 also seems a curiosity. On one level, it makes sense as an appropriation of the material of popular music, reconsidered within the context of the public space of the gallery. Yet claims about Dashper’s works and their associations with the ‘lens of popular culture’ overstates an argument about the artist’s sparse vinyl album covers and discs that are more intimately connected to the legacy of Marcel Duchamp.

And where does Ani O’Neill’s Five Little Piggies fit in Your Hotel Brain? A work that utilises traditional skills of crochet, sewing and tivaevae, it reveals a complicated set of responses to digital experiences in the 1990s and 2000s by asserting the presence and politics of indigenous peoples. Five Little Piggies provides evidence of a more subtle story of the history of art, not so much about appropriation but about the politics of culture and the revitalisation of the hand-made and traditional crafts in the late 20th century.

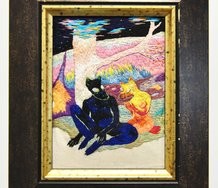

Although for the above reasons this exhibition frustrates at times, returning to it also renews interest in the work of a number of artists. On first encounter, two distinct groups of paintings—one of Seraphine Pick, Tony de Lautour and Saskia Leek; another of Bill Hammond, de Lautour, Grant Takle, Jason Greig and Peter Robinson—initially and predictably looked and felt like that Canterbury School of ‘pencil-case’ artists, a phrase coined by Strongman in the catalogue for the 1995 touring exhibition, Hangover, that she curated with Robert Leonard. Surely this is the obvious genesis of Your Hotel Brain, with seven of its eighteen artists also in Hangover, (de Lautour, Greig, Hammond, Leek, Robin Neate, Robinson and van Hout).

Yet many of these paintings and objects no longer seem steeped in ‘bogan and bad-white art’ attitudes. The provocation that they once represented to serious painting over twenty years ago is gone. It now comes as a surprise to witness tangible evidence of their faith in, for example, painting as a means of making an important statement or commentary on the human condition. So, although the clustering of this group again might have initially appeared repetitious—it also reiterates former curator Elizabeth Caldwell’s selection for Skywriters & Earthmovers, a 1998 exhibition of Canterbury artists that included Hammond, Cotton, Heaphy, de Lautour, Robinson, Takle and Pick—it seems more than worthy of new consideration.

Thus the paintings by the Your Hotel Brain artists collectively puts a lie to the premise of their being street-wise painters interested in bad taste, showing instead, their faith in painting as a particular means of communication. This connects them closely to traditions of Modernism; especially German and Abstract Expressionism, American Pop Art and Neo-Expressionism. They may have once appeared dressed as the anti-Christs of the future of painting but in de Lautour, Hammond, Pick, Robinson and Takle’s work there is an assertive and unspoken faith in art as an experience that has the potential to change lives, an attitude that connects their work to artists like Cleavin, Clairmont, McCahon and Woollaston.

In the late 1990s, Robinson’s Mission Statement: First we take Island Bay then we take Berlin, 1997 - 1999, was a confronting painting. Making public a scathing list of tactics on how to be successful in the art world it breathed a contemptuous life into an aggressive and dominating neo-liberalism. Yet, what then seemed like full and frank disclosure, now in 2018 reads more like a series of ‘alternative facts,’ rendering it much more complex and interesting.

Robinson’s other contribution to Your Hotel Brain is Das Es, a large and imposing sculpture that possesses all the grossness and humour of the work of artists like Sarah Lucas, Franz West or David Shrigley—only more so. Described in the gallery wall text as being ‘antagonistic towards conventions of polite taste,’ Das Es has a dominating presence. Here Strongman’s accompanying commentary is at its best, politely describing Robinson’s ‘doughnut and sausage’—‘O’ and ‘I’—as a kind of deflation of the binary code prints and installations that the artist made in 2001. Although playfully complementing and conversing with the formal circular target of Shane Cotton’s Untitled (Head), 2012, it also calls out to all surrounding works in the exhibition to account for themselves—providing reason enough, all on its own, for us to take time out to visit, and return to again.

Warren Feeney

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.