John Hurrell – 9 January, 2018

The third in a sequence of anthologies of writing about Len Lye, this volume accompanies the 'Stopped Short by Wonder' survey currently being presented at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu—curated by Lara Strongman. The first collection, a split English/French volume, appeared with 'Len Lye' at the Centre Pompidou in March 2000, and the second—a large and colourful publication—was with another 'Len Lye' at the ACMI in Melbourne in 2009.

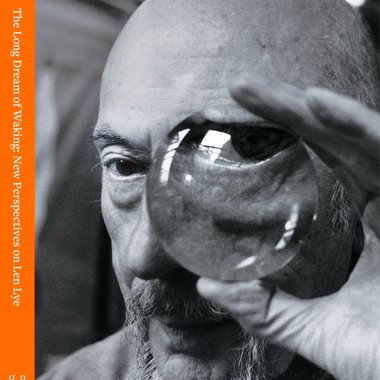

The Long Dream of Waking: New Perspectives on Len Lye

Edited by Paul Brobbel, Wystan Curnow and Roger Horrocks

Contributions by Scott Anthony, Geoffrey Batchen, Paul Brobbel, Rex Butler, Wystan Curnow, Sarah Davey, A. D. S. Donaldson, Alla Gadassik, Shane Gooch, Roger Horrocks, Aaron Kreisler, Malcolm Le Grice, John Matthews, Peter Selz, Luke Smythe, Evan Webb

224pp, softcover, b/w and colour illustrations.

Canterbury University Press, 2017

The third in a sequence of anthologies of writing about Len Lye, this volume accompanies the Stopped Short by Wonder survey currently being presented at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu—curated by Lara Strongman. The first collection, a split English/French volume, appeared with Len Lye at the Centre Pompidou in March 2000, and the second—a large and colourful publication—was with another Len Lye at the ACMI in Melbourne in 2009. What the third anthology lacks in sumptuous sensuality it makes up for in its wider range of subject-matter. There are over a dozen essays here—looking at all sorts of aspects of Lye’s practice. (Three of these writers are also in the new Walters book, so that is interesting if you want to search for consistent over-arching authorial attitudes, or ponder the paucity of active art historians.)

Some of these also discuss other New Zealand (or Australian) artists in depth —artists with parallel similarities to Lye-and in some ways the focus of the volume on occasion gets lost, as if Lye is being used to piggyback other talents into the public gaze, while he himself steps back into the shadows. The essays by Wystan Curnow (looking at innovative New Zealand ‘light-suffused environments’), and Rex Butler with A. D. S. Donaldson (examining Australasian ‘modernist primitivism’), consequently seem a bit forced and distracted by material that would normally go in footnotes, as if there wasn’t enough new biographical information on Lye available to be incorporated, and so other talents were used as padding. The essay on Lye’s years in London (by Scott Anthony) for example is infinitely more successful than Butler and Donaldson’s look at his time in Sydney. Here Lye occupies centre stage at all times, as you’d expect.

There are some immensely interesting contributions to this book. Evan Webb, the constructor of the posthumous Lye kinetic sculptures, describes in detail the importance of the plinth to Lye’s thinking, and his various techniques for noise control and hiding the motors that energised the moving components. Roger Horrocks looks closely at Lye’s taste in music, how his interest in jazz developed, and how he researched the rhythmical soundtracks for his extraordinary films. Alla Gadassik discusses his technique of using tiny stencils and paint directly on the film strip, while Sarah Davey describes the motivation and setting up of the Len Lye Foundation, and Geoffrey Batchen Lye’s production of cameraless photographs.

Luke Smythe and Roger Horrocks present two papers on Lye’s interest in motion as the key element of his practice. Smythe examines the role of imagination in creating empathetic structures of movement while Horrocks looks at the process (the overall kinetic activation of steel elements, types of connected movement patterns—rather than frozen images) in the sequencing of programmed ideas.

Such thinking seems aligned with the research based practices of artists like Stevenson, Denny, Enberg, Parker or Starling, where different forms of tropic metamorphosis are explored or blended (disparate subject-matters or substances transmuted)—or formal permutations tested—in order to arrive at a semantic focal point for the artwork.

Lye’s obsession with physical motion can here be seen as a metaphor for the movement of thought, for the shifts of articulated consciousness. To look at another artist who treated the activity of the human body as a trope, it could be an extension of Paul Klee’s famous concept about drawing: ‘An active line on a walk, moving freely, without goal … A walk for a walk’s sake …’—except that Klee in his process of alluding to the shapeliness of thought was thinking of an initially destinationless trajectory, a unplanned exploration, rather than (eventually) a repeatable conglomeration of sequenced vectors, a patterned cluster of carefully controlled movements.

The yellow middle book is my personal favourite of the three anthologies—I like its design very much (Kalee Jackson) and the topics covered in the essays—but while this later collection doesn’t foreground Lye’s exuberant imagery over the commentary (only himself as strong-willed personality via the corny cover) it is indisputably handy. Extremely informative and easy to read, it is both a healthily provocative stimulus and for Lye disciples, a reinforcer of settled-in (but still experimental) values.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.