Terrence Handscomb – 4 January, 2018

If Fresh and Fruity were to abandon their theatre of triumphalism and actually spark the sort of chaotic singular occurrence that would be needed to efface the hierarchies of privilege and power that already mandate New Zealand's large public art institutions, there will never be enough palliative analgesic for them to survive long enough to ever reach the promised land that they undoubtedly believe to be so close.

The excited appearance of a new generation of New Zealand artists, who bring with them a new and raw veracity, seems to be a reoccurring feature of New Zealand’s arts culture; albeit a constructed one. New young voices are not only sought but also required to speak new truths in compelling ways, and to also perpetuate the myth of artistic renewal. In the age of impotence the raw honesty and intuitive vision that is often assigned to emerging young artists—and one which is usually contrasted with the over-rehearsed practices of their stayed, mature, and usually boring older counterparts—appears now to be more poignant than it is prophetic. (i) Note: endnotes are numbered in lowercase Roman numerals.

Every now and then a big show of emerging artists opens in a major New Zealand art gallery. The institutional willingness to recognise and support emerging young New Zealand artists and to hear and seriously consider what they have to say, was witnessed in the size and scope of the Adam Art Gallery exhibition The Tomorrow People curated by Christina Barton, Stephen Cleland and Simon Gennard (Adam Art Gallery, 22 July-1 October 2017).

Although the range of art in The Tomorrow People was wide (the project included three commissioned essays), one seminal work stood out: Manifesto vol 1: Fresh and Fruity is a sexy new look (2014/2017, printed poster, vinyl wall text)—hereafter denoted ‘Manifesto.’

Originating in Dunedin, Fresh and Fruity is a “wāhine” collective who directly challenge the institutional power of the art world, while questioning “… the relevance of having a hierarchy or ‘directors’” but to instead find “new ways to work as a collective.” (ii) But it was the sardonic way in which Manifesto overrode formal meaning with rhetorical perlocution, that made the work significant.

The installation of Manifesto consisted of a pile of printed manifesto-posters placed elegantly on the gallery floor (no grunge ethic or punk sensibilities here, it all lines up) and a vinyl wall text that read: “As a condition of our engagement with The Tomorrow People, Fresh and Fruity has proposed that the Adam Art Gallery create its own safe policy and procedures in consultation with other galleries and relevant organisations.”

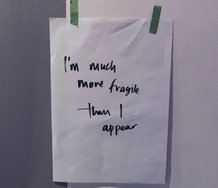

While the emphases of the text were plural—politico-cultural challenge, establishing artist safe places, consultive and non-hierarchic arts policy making—an uncharitable first reading aggravated the suspicion that the steady inculcation of university liberal ethics committees in our major art teaching institutions had produced a generation of artistic wimps, whom no doubt have come to believe that they are entitled to ethically informed cultural protections against the brutal but long established critical mechanisms of the art world.

Even though this reading of Manifesto was plausible, it was unlikely. This all-women work defiantly mixed the stereotype of women’s values, female sensibility, domestic safety, indigenous respect, and cultural protection with the less convincing honky aesthetics of twentieth century Western revolutionary activism.

Yet, the humour and cynicism of Manifesto‘s full title and the bolshy agitprop poster text did exactly what provocative young artists quickly learn to do when they discover the power of their own independence and learn to assert their own values: mix sarcasm with youthful conceit, and if you are still worried that whatever you say and do will not be heard, nor taken seriously, then come down super-hard. Otherwise, mix in a bit of levity and provocation with the expectation that it will diminish the authority of your detractors, and give them no clear target for retaliation.

Manifesto‘s curatorial placement in The Tomorrow People amplified its rhetorical voice, but the work became inextricably bound to the modernist trope that infects all New Zealand’s major art institutions: that which claims to be fresh and new will define itself in response to that which is old and stale. The new will continue to force the old to reconfigure itself until such time as the once-was-new is erased by something newer: a new new. (iii) The history of art is a history of erasure.

• • •

Valerie Solanas’s cult classic SCUM Manifesto—which Solana sold on the streets of New York’s Greenwhich Village in the form of mimeographed sheets in 1967—shifted effortlessly between satire and serious critique; whereas the separation of style and serious political concern in the more youthful Manifesto became diminished under the aegis of The Tomorrow People.

Marxist theorist and writer Mark Fisher sums this up quite nicely:

Witness, for instance, the establishment of settled ‘alternative’ or ‘independent’ cultural zones, which endlessly repeat older gestures of rebellion and contestation as if for the first time. ‘Alternative’ and ‘independent’ don’t designate something outside mainstream culture; rather, they are styles, in fact the dominant styles, within the mainstream. (iv)

To which should be added: in the context of The Tomorrow People, ‘rebellion and contestation’ is the dominant style of Manifesto, but for Fresh and Fruity this was unproblematic.

With its verbal taunting, Manifesto opposed “the sterility of the white wall gallery system” (32) (v) [note: numerals in parenthesis denote the numbered Twitter-length “manifesto” statements in Manifesto’s give-away poster text]. Yet, Fresh and Fruity inculcated themselves into the very space that they deplored, which in this case, was the plain white walls of Adam Art Gallery. Undoubtedly, it can be quite effective to take the fight to the enemy with a Trojan horse tactic (“Fresh and Fruity strives towards disrupting hierarchies in a fuck you #doingme attitude” (44)); or feigning indifference in the face of contradiction (“Fresh and Fruity does not give a fuck about becoming or pleasing an institution and becoming famous” (58)); or rhetorically asserting that Manifesto‘s gallery inclusion formed some transgressive paratopia which paradoxically occupied two opposing places at the same time.

But this sort of thinking probably concealed the less worthy likelihood that a group of young cultural activists, who despite their rhetorical protestations, could not resist the attention their project would garner by being included in a large public exhibition, nor bear the umbrage of being left out.

The collective Fresh and Fruity effectively sidestepped such anti-institution-but-still-in-it contention by locating its main operational clout, not in the established public gallery system, but in the participational community-based utility of social media. By cleverly evoking the Ngāti Kahungungu mythical image of Pania of the Reef and mixing it with the acceptable face of social media (42, 50, 68, 90), they formed an emblematic “Pania of the digital reef.” In so doing, Fresh and Fruity neatly induced symbols of straight-male cisgendered egotism (28) in the figure of Pania’s deceptive lover Karitoki. (vi) Consider Manifesto‘s puissant line: “Fresh and Fruity is facilitated by Pania of the digital reef and doesn’t place any value on neocolonial patriarchal hierarchies because lol” (18). Thus, the mythical figure of Karitoki came to personify the sort of male perfidy, betrayal and broken promises that are emblematic of the art world’s commercial and institutional duplicity and the male privilege that this engenders.

“Fresh and Fruity primarily exist as a social media practice” (40) in which the spirit of trusted whānau, soapbox sloganeering, and the participational functionalism of social media become inseparable. But in so doing, Fresh and Fruity elevate the cultural phenomenology of social media to that of trusted friend, while naïvely ignoring the duplicitous character of the social technocracies that support it. British theorist Mark Fisher sees social media and the fake liberation it offers in a more cynical light. Fisher’s neo-Marxist thinking claims that we now live in a time in which not only millennials, but every generation and culture, are affected by the insidious reach of technocratic capital. Social technocracy has diminished (a Marxist reading of) history to the point where the grand narratives of intervention that are supposedly enabled by the widening reach of social media, have become impotent. (vii)

Every move made by people bound up in the seductive folly of social media, has already been technologically anticipated, tracked and has been bought and sold before it has been given a chance to happen. “Today money is a self-referential sign that has acquired the power of both mobilising and dismantling the social forces of production,” as Franco Berardi puts it. (viii)

So what is to be done? Swedish poet and founding member of the Stockholm Surrealist Group (1986) Aase Berg asks: “… so how are we to dismantle systems to which we are parasitically linked? How can we fight a network that not only demands our consumption, but which in fact conditions our bodily and psychological existence?” Berg has a simple answer: hack it, “fuck up the system from within.” (ix)

As efficaciously as Manifesto seeks to fuck up the institution from within, Fresh and Fruity seem blissfully unconcerned that their technocratic social-media overlords could be quietly doing exactly the same thing to them: “Corporatised social media is key to Fresh and Fruity’s practice” they proudly declare, without a hint of the deep acquiesce and nuanced servitude that this phrase entails. (x)

However, it is a mistake to pathologise Manifesto to the point where it is critically silenced by the myopic thinking of neo-Marxist theorists or by the factional thinking of cheerless poets with dystopian views of twenty-first century technology. Even if the capitalist underpinnings of social media are the same as those that rule the art world—the art world that Manifesto despises—this still doesn’t provide reason enough to rescind Fresh and Fruity’s provocative intention. Even if the communal character of social media and a corrupt art world serve the same crooked master—capital—Manifesto nevertheless exudes the sort of fanciful hope that drives both the heart of revolutionaries and the dreams of the disenfranchised, and this is not easily undone.

• • •

Manifesto has a simple intention: evoke a cultural narrative that points to a number of extrinsic cultural conditions, which themselves point towards new hopes and new futurities.

In his online review of The Tomorrow People, Mark Amery effectively encapsulates the one articulateed by Manifesto’s wall text:

“What expectations should there be of a public gallery as a safe space? And when does that run counter (to adopt a slogan of Wellington Māori and Pasifika artist community collective Kava Club) to being a ‘safe place for unsafe ideas’? What should safety mean for artists new to working in a big public gallery space? And should it also impact on how galleries welcome those artists’ communities? Whose culture is this gallery culture anyway?” (xi)

The image of the daunted young standing before to the face institutional power, was dramatically characterised by Colin McCahon’s powerful invective Am I Scared. (xii) The painting was motivated by McCahon’s response to a photograph of two young Māori men apprehensively entering a large public art gallery. The text and sentiment of that painting (“AM I Scared Boy (EH)”) was later echoed by Peter Robinson in his 1997 painting Boy Am I Scared Eh!. (xiii) Twenty years ago I read Robinson’s great work as marking the cultural recovery of an entire people. Now I read it as a text portending the comprehensive forfeiture of self in the age of impotence—and of that, we all should be scared. (xiv)

Yet unlike the subject of McCahon’s painting, it is without trepidation that Fresh and Fruity choose the shifting ground of political agitation from which to taunt the big public galleries, whose exclusivities and hierarchies they seek to disrupt “… in a fuck you #doingme attitude.“ (44).

But in the end, if Manifesto‘s call for institution-mandated cultural safeplaces were to materialise, this new hope would in all likelihood devolve into a flattened out rapport de force. This is the principle of institutional levelling. If a Tocqueville effect exists in art, then the energy and enthusiasm of emerging young artists entering cultural safe zones will likely become deadened. This is because artistic frustration will increase as artists’ comfort improves. That is, if the Tocqueville theory of social frustration has an arts corollary, then its realisation will likely lie in the cultural safe zones of large institution. (xv) If so, then the range of social and cultural potentialities evoked by Manifesto will eventually flatten into strings of institutional conformities.

Despite Manifesto‘s built-in critical armour—its witty piss-take title (1, 3, 5, …etc.), its laudable anticapitalist and anti-institution rhetoric (56, 88, 92), its praiseworthy abhorrence of ethnographic neo-colonialism (18), its angry distrust of the exploitive business practices of the new university (62, 64), and its mocking distain of white cisgendered male egos (28)—there is something cautionary to be garnered from this work. If Fresh and Fruity were to abandon their theatre of triumphalism and actually spark the sort of chaotic singular occurrence that would be needed to efface the hierarchies of privilege and power that already mandate New Zealand’s large public art institutions, and then survive the covert enmity, disdain and instinctive self-preservation of those whom already hold that power, and further maintain the fight until the political fallout becomes so severe that Fresh and Fruity were to find themselves in the wilderness and not in exhibitions like The Tomorrow People, then there will never be enough palliative analgesic for them to survive long enough to ever reach the promised land that they undoubtedly believe to be so close.

Yet a culture of despair is not Fresh and Fruity’s mandate. Their project is an attack of what amounts to be the prosperity and privilege of the few and the hegemonic power that enables it. For this, Fresh and Fruity is indeed a sexy new look. Their project is no maudlin poïesis of something once loved but now lost; nor does it cynically indulge in the stark realism of failed revolutions. They are too young for that. Their voice is one that is part of a transnational e-based art retaliation in which many words are collectively spoken and many voices are collectively heard: (xvi)

“Having no body and no name is a small price to pay for being wild”

“I am the supercommunity, and you are only starting to recognise me. I grew out of something that used to be humanity. Some have compared me to angry crowds in public squares; others compare me to wind and atmosphere, or to software.”

“Historical pain is my criteria for deciding the pricing of goods and services. Payback time is my favorite international holiday, when things get boozy and a little bloody. Economies have tried to tap in to me. Some governments try to contain me, but I always start to leak.” (xvii)

These are the voices of what Berardi calls futurability in the age of impotence and what others have called a diabolical togetherness beyond contemporary art. (xviii) The young are good at constructing possible futures because the burden of history is less for them. Even if those futures are no more than the indices of wilful optimism, for this we should still be thankful lest those of us without real power would wallow too long in self pity.

Terrence Handscomb

(i) Cf. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, Futurability: the age of impotence and the horizon of possibility (London: Verso, 2017).

(ii) Loulou Callister-Baker, “Hello Girls: Fresh and Fruity Interview,” Critic, Issue 14, 5 July 2015, https://www.critic.co.nz/culture/article/5039/fresh-and-fruity.

(iii) Cf. Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: is there no alternative? (Hants, UK: O Books, 2009), 3.

(iv) Ibid., p. 9

(v) Numerals in parenthesis denote the numbered “manifesto” statements in Manifesto‘s give-away poster text.

(vi) “Fresh and Fruity laughs at the banal, white, cis, male ego” (28).

(vii) Fisher op. cit. 3-10.

(viii) Franco Berardi, op. cit., 149.

(ix) Marty Cain, “What Is Called Freedom Is a Frozen Freedom,” poetry review of Hackers, by Aase Berg, Boston Review, 12 October, 2017.

(x) Loulou Callister-Baker, op.cit.

(xi) Mark Amery, “Giving Shelter,” The Big Idea, 16 August, 2017, https://www.thebigidea.nz/stories/giving-shelter.

(xii) Colin McCahon, Am I Scared, 1976, acrylic on paper, 730 x 1105 mm, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery.

(xiii) Peter Robinson, Boy Am I Scared Eh!, 1997, mixed media on paper, 2270 x 2250 mm, Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

(xiv) Cf. Franco Berardi: “I do not identify impotence with powerlessness. Often when lacking power, people have been able to act autonomously, to create forms of self-organisation and to subvert the established power.” op. cit., 26, 41-42.

(xv) The Tocqueville effect in social anthropology occurs when “social frustration increases as social conditions improve.” This is the unintended consequence of social equality. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Vol. 2 (1835-40), Ch. III. I have simply replaced ‘social frustration’ with ‘artistic frustration,’ for but the principle remains the same.

(xvi) I am thinking of the e-flux journal project at the 56th Venice Biennale in which many of the issues expressed by Manifesto were spoken. In Venice e-flux produced a single issue over a four-month span, publishing an article a day both online and on site.

(xvii) “Supercommunity: Editors’ Introduction,” in Julieta Aranda, Anton Vidokle, and Brian Kuan Wood, eds., Supercommunity: diabolical togethernesss beyond contemporary art (London: Verso Books, 2017). 9-10. This book is a collection of the e-flux Venice project texts.

(xviii) Ibid.

Recent Comments

Ralph Paine

Thing is Terrence, Fresh and Fruity's comment may or may not have been about you.

Terrence Handscomb

To G. Yes, yes … “spawned” may have been better usage, but I couldn’t abandon the image of cultural pestilence. ...

Terrence Handscomb

FYI: “Manifesto vol 1: Fresh and Fruity is a sexy new look,” 2014/2017, printed poster, vinyl text, courtesy of the ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 11 comments.

Comment

Ralph Paine, 2:46 p.m. 8 January, 2018 #

I.

OK, but aren’t tomorrow’s safe places gonna be hidden places, secret places, places without cameras or microphones, places requiring “One Hash Tag Less” rather than any further proliferation of hash tags? And likewise, isn’t our coming safe passage gonna require (analog) pass words/gestures rather than the propagation of order words as presented in radical-chic manifestos?

Well yeah, guess this does all depend on our relation with the institutions. It’s gotta be said that always already the institutions are about identity and representation, about the codification of norms and the taming of conflict and contradiction... So, when along come the Fresh and Fruity collective with their by now hyper-standardised identity politics and youthful oversupply of conflict and contradiction for sure the institutions are gonna jump at the chance of getting them onboard and on side.

This was never gonna be difficult, simply because the collective thinks institutionally. In other words, all of Fresh and Fruity’s critiques and demands were on the official institutional agenda decades ago. From workplace health and safety to human rights, from diversity to anti-bullying, from bi-culturalism to sexual harassment, etc. etc. and including the white cube problem, the community access problem, the hierarchy problem, the artist’s fee problem, etc. etc. doubtless Fresh and Fruity’s program IS the institutional program.

Ralph Paine, 2:47 p.m. 8 January, 2018 #

II.

So where’s the coming down hard, the unsafe ideas, the f_cking up of the system from within, the new new? And where indeed the self proclaimed sexiness? Perhaps getting a sense of the latter is where the techno fetishism of the collective’s social media practice comes in: the de-vice, the liquid crystal screen, the early MTV-vibe, x-gendered Tumblr communities, Instagram’s Polaroid-nostalgia, emojis, likes, art-porn, reposts, etc. etc.

Problem is, I’m figuring 2017 (the year Mark Fisher committed suicide) as the year when net-utopia (and much else) finally sunk itself into a vast ocean of e-waste and what amounts to slave labour; when Trump’s pathetic late night tweeting was all it took to set the political world on fire; when financial abstraction now coincided directly with extraction and each day Bitcoin speculation consumed more energy than most cities; when the alt-right muscled-up via social media, when etc. etc. All this casts a deadly pall over any remaining libidinal zeal (young, old, fancifully hopeful, accelerationist, whatever) for a now “Crowned Technic.”

Whatever it is that’s to be done, without a doubt the institutions and the likes of Fresh and Fruity ain’t doing it... And no mass chanting of the “F_ck u I’m doing me” mantra (talk about ya basic neoliberalism!) is gonna change that. But yeah, here in the nonlinear mean-time of an apocalypse that’s already happened there’s a new wild forming, growing, scattering.... “I don’t want security, I want to leave, and then disperse myself everywhere and all the time ... I am the supercommunity, and you are only starting to recognise me.”

Fresh And Fruity, 11:21 p.m. 25 January, 2018 #

Teach me daddy.

Terrence Handscomb, 9:46 a.m. 26 January, 2018 #

I’d love to.

When should we start?

What should I wear?

Do I need to bring anything?

Terrence Handscomb, 9:48 a.m. 26 January, 2018 #

… but be careful, I’m libidinally challenged.

Daniel Sanders, 6:17 p.m. 26 January, 2018 #

Terrence, it is generous of you to offer your time and thoughts for this work. But, what was a controversial criticism, has now been positioned as an out right attack on a young Maori female collective as proven with your comments. I might suggest you refrain from commenting, as I interpreted your latest comment towards Fresh And Fruity as a sexual threat. It would appear then that your motivation is simply that, to provoke and attack, to 'rark up'. In your criticism where you seemed to offer some insight for millennials, positioning yourself above them, you have contradicted yourself in the comments by acting like one. But at least a millennial would know that sexual threats are not okay. Sorry Daddy, maybe let Fresh And Fruity teach you.

Terrence Handscomb, 7:48 p.m. 27 January, 2018 #

Thank you for your considered comments, but FFS lighten up. It was a joke given back in the same tone as that which provoked it: sardonic humour. It was not an attack! Dah! In the same way as FnF’s trolling comment was funny, albeit with a serious edge that is typical of their MO, my comment was simply a respond in kind, which you somehow believe I should have risen above. Social-media trolling—FnF’s favoured textual milieu, the evidence of which is rife in "Manifesto"—has one principle efficacy: make any response in kind look unhinged. Trump learned this early.

Satirical provocation, especially when it’s libidinal, is an affective two-way communication that, if allowed, can cut to the heart of age and gender profiling. Satire is very effective at this and so are FnF, although I think they will be loathed to call it satire. But FnF also get away with being hard-arse millennials because either no one bothers to answer them back, or the outrage police ride to their rescue. Get off your high horse, FnF are quite capable of looking after themselves.

We are living in the age of #MeToo and, without doubt, the cultural climate of outrage that it has spored. Not even the smartest satire is now immune. Despite #MeToo having valiantly give voice to women hurt by the violence of male power and the ugly secrets that have enabled it for too long, it’s both sad and disappointing to see that #MeToo also means that it is therefore unwise for males (and especially older males) to criticise women’s values, no matter how innocent or benign the content of that criticism may be. Someone will get offended and outraged, then go looking for blood. It’s a pity you also went that way, because I have never shirked away from the cultural dangers of being inappropriate. This means that now suspicion will always colour my textual relationship with FnF–albeit restricted to EC–and diminish its ambiguity. It’s also disappointing to see how easily the burgeoning textual fluidity of this relationship has been moderated by moral interference. In the arts this is always a threat.

“Teach me daddy” has a libidinal component that, in a very clever way, provokes a whole range of connotative entailments that lurk in the dark zones of age and gender stereotyping. FnF are quite happy to play with this, but they can’t have it both ways, and this was my point. Despite their bad-girl-millennial persiflage, FnF are really cleaver at what they do, and to my thinking, they are also very funny. Similarly, it’s a pity you didn’t recognise in my reply, the self-effacing humour with which it was delivered and playful intention with which it was given (#joke, #vomit, #yuk, #inappropriateHumour, #libidinalDelusion, #outToPasture). But I’m also not so deluded to think that everything I write and say will be understood as it is intended to be nor, for that matter, turn out be any good at all.

BTW, the enduring principle players of FnF are not Māori. Someone correct me if I’m wrong.

Ngapera Kaweroa, 8:06 a.m. 28 January, 2018 #

This isn’t criticism as it does in no way benefit the writer nor the artists.

But if the writer had done any research or spoken to anyone (hell maybe even fresh and Fruity?!?) or had any editorial support whatsoever you would know that this work is four years old and titled ‘Fresh and Fruity is a sexy new look’ not manifesto. It’s also one of around ten texts written over the last four years all easily accessible online. They would also know that both artists are Māori.

But teach me Daddy ur so wise !

U are a creepy pervert who can’t get it up maybe u should work on that, but just do you ae ;)

Lots of love,

A very young dumb millennial xo

Terrence Handscomb, 3:44 p.m. 28 January, 2018 #

FYI:

“Manifesto vol 1: Fresh and Fruity is a sexy new look,” 2014/2017, printed poster, vinyl text, courtesy of the artists.

http://www.adamartgallery.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/AAG_Exhibition-Booklet-1Aug_Singlepages.pdf

For brevity, “Manifesto” is my colloquial shortening of the full title.

#EggPlantEmoji

Terrence Handscomb, 3:46 p.m. 28 January, 2018 #

To G. Yes, yes … “spawned” may have been better usage, but I couldn’t abandon the image of cultural pestilence. XT

Ralph Paine, 10:47 a.m. 30 January, 2018 #

Thing is Terrence, Fresh and Fruity's comment may or may not have been about you.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.