Terrence Handscomb – 25 January, 2022

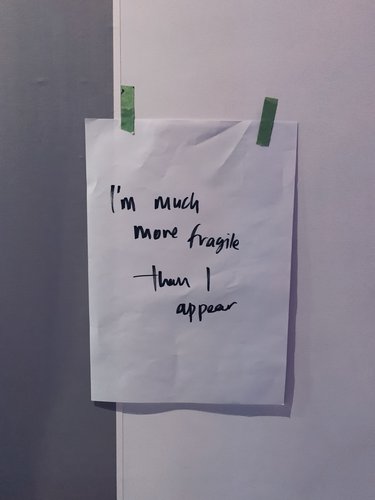

Appearing to be strong, whole and in control of how one presents oneself to others is tied up with how you want others to see you. But this last part usually involves a deeper social pathology based on a generalised need for social acceptance and recognition. When personal pathology is best exploited in art, it places the subject in a brutal and confrontational proximity to some inaccessible alterity which presumably the art will identify.

EyeContact Essay #45

When you are locked-down under COVID-19 Alert Level 3 for as long as Auckland was last year under the Delta variant—and who knows what it could be under Omicron—what do you do to get by? You waste a lot of time in front of a screen, send away for books and go back over every critical theory title in your library.

In former times—which for me always entailed the now distant memories of living in pre-COVID foreign cities—being holed-up in the pre-gentrified bohemian enclaves of 1990s Berlin, or fluffing about the rich summery towns of Southern California in the 2000s I would have done what I have always done when I’m culturally depressed or socially bored, I would have gone shopping.

Or during desperate times—and I mean the times when artists are forced to confront the intellectual and psychological uncertainty about who they are and what they should be doing—I would have done what I always done: I’d get dressed up and go shopping.

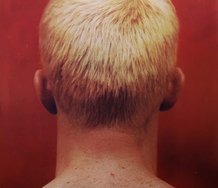

If how you present yourself to the world involves wearing expensive fabrics and overpriced, provocatively designed garments; and you love the principle of taking the result of someone else’s skill and imagination and put the result of their vision on your own body and wear it as if it were your own new younger skin—a radiance you could never emulate without them—then you will soon realise that securing the services of a good hairdresser is imperative. Bad hair, it turns out, has been one of the most disastrous social consequences inflicted by any COVID-19 lockdown.

Add to this a sense of being under cultural house arrest, a condition I felt, when after many years living abroad, I returned to live New Zealand. The stay-at-home condition of a strict COVID lockdown, makes one prone to torment by that species of social paranoia—otherwise known as rejection—that pushes one to imagine the worst.

I’ve been calling friends in Berlin, just to speak German and to wrap myself in the imagination that, if only for a moment, I am living in a world in which COVID had never struck, somewhere that is not New Zealand.

But this has sort of thinking has become an exercise in self-delusion because it always ends in the same place: the realisation that being trapped in a small cultural space means that you will never be licensed to say and do what you want. The price of freedom is often a moral cost imposed by others. If these cannot be entirely laughed off they will be internalised, and it is here that the battle of consequences must be fought. So shopping became one of my many lockdown fantasies, nicely constructed to sidestep the realisation that freedom is not absolute.

Yet my idea of ‘shopping’ involves the bourgeois paradox belied by those of us with great sartorial pretensions, but little money. When I say ‘shopping’ I mean an activity that involves walking into elite overpriced couture houses in Europe and North America (there are no equivalent places in NZ) looking like a million bucks but with no intention to spend. Because I have been (and still am) without the exorbitant resources needed to support the pretensions of high living, I would not have the means to purchase anything. I just wanted the attention, and with it, a sort of deceitful confirmation that I was indeed a good person. If only things were different. Such a doomed psycho-social strategy is already a zero-sum game because the principle of diminishing returns holds until a point of sale is expected, after which the game is lost.

On 26 September last year the enigmatic Spanish artist Amalia Ulman released her new semi-biographical film El Planeta, which opened in New York theatres, screening thereafter at theatres around the US. Being an artist’s film, El Planeta entails a process that many artists adopt in order to transcend their own doubts and personal failings, they fetishise them by turning them into art. Although the film simulates many of the personal misfortunes (mainly material) Ulman faced in her own life, the narrative arc follows a familiar story of failing prosperity: “… a mother and daughter (played by Ulman, 32, and her real-life mother, Alejandra Ulman) refuse to acknowledge that they are about to be thrown out of their tiny apartment in Spain. They spend their days playing rich, draping themselves in zebra-print Moschino suits and fur coats, and waltzing around their recession-ravaged seaside town charging fancy meals to the tab of a possibly invented politician boyfriend …” [3]

While doing a round of promotional interviews for the release of her film, Ulman met with New York Magazine writer Rachel Handler. Hilariously, Ulman and Handler met in the NY Bloomingdale’s Giorgio Armani enclave with the intention of getting kicked out for the most egregious dereliction: not buying anything.

After about 30 minutes of sitting around in the plush setting, the pair were approached by a female sales associate. Handler reports: “‘Ladies, I’m sorry,’ [the sales associate] says, smiling intensely to indicate her awareness that we have neither the intent nor the means to purchase Armani’s wares. ‘I think you might be more comfortable in the furniture department.’” [4]

Of course, Ulman getting kicked out of Giorgio Armani was a setup, but it had artistic efficacy, and Ulman knew it. Artists often replicate real life situations, especially adverse ones, by simulating them in elaborate artistic constructions. But for Ulmen, getting kicked out of Armani was a little bit of art, a bit more film promotion, and a lot of trumped-up irony.

Under NZ’s COVID strictures remedial shopping—if that’s at all possible in New Zealand—and defiant artistic interventions à la Ulman, would have to be enacted online; but this doesn’t really work. So pretending to be rich and wandering around elite couture houses in NY, LA and Berlin like I was used to, is under COVID, wholly implausible. You would have to create a social media presence in which looking and seeing no longer involve the materialist ontology of actually being there, and instead, involve states of representation whose accessibility and intensity become algorithmically exaggerated by the profit-driven greed of Silicon Valley.

Fronting up to a camera is not the same as fronting up to other human beings and it is here that the intersection of personal paranoia and social representation occurs. But contriving to represent oneself to others can be a dangerous game, one which is easily lost.

To those of us who continue to play zero-sum games in the social arena, but neurotically choose only games which we will probably lose, our game will usually entail some sort of pathological disquiet, of a sort that artists love to turn into art. Artists often inoculate themselves from the consequences of personal loss and failure by veiling them with intrepidity and humour. The power of self-satire can distance an artist from signs that tell everyone that all may not be well. We are all helpless when those signs bore through the skin to get out, to become visible and thrive in the light of day as symptoms.

Appearing to be strong, whole and in control of how one presents oneself to others is tied up with how you want others to see you. But this last part usually involves a deeper social pathology based on a generalised need for social acceptance and recognition. When personal pathology is best exploited in art, it places the subject in a brutal and confrontational proximity to some inaccessible alterity which presumably the art will identify.

Alongside her recent film release, Amalia Ulman is perhaps best known for her 2014 personal image work Excellences and Perfections, an Instagram-based work in which she posted photos of herself in various stages of what appeared to be a nervous breakdown. The performance was, in the words of Handler, “Los Angeles latte art involving pouty selfie videos (“Haha so dumb didn kno i was recordin”) “that escalated into a breakup spiral, plastic surgery, sugar-baby ventures, and eventually Goop-y inner peace (“#grateful #namaste #healthy”) … Afterward, she was both accused of being a hoaxster and lauded as “the first great Instagram artist.” [5]

When artists turn the camera on themselves in ways that replicate a social media postings, like Ullman’s selfie works, a rich mixture of self-satire and genuine pathos is often evident.

This was certainly evident when Auckland artist Natasha Matila-Smith’s set of selfie-body photographs were included in her large mixed-media installation I Think You Like Me But I’ve Been Wrong Before, exhibited last year at Artspace Aotearoa. Matila-Smith exhibited alongside recent AUT graduate Alice Sparrow. Although Matila-Smith’s large installation looked like something just-out-of-Elam-but-with-a-better-budget, her photographic work is exceptional. Her photographs capture the quotidian pathos of a lonely XXL size young woman spending too much time at home, in her bedroom, with her phone on Instagram.

As much as Matila-Smith’s and Ulman’s work converge in a shared social media ethos (although Matila-Smith’s selfies only look like they do) the two diverge inasmuch as the Auckland artist is nowhere near as good looking, as slim, nor as “racially privileged” as Ulman. Because of this, and the ideological distance between New Zealand art and the rest of the world—which is a hard-ass and critical place—Matila-Smith’s bedroom-selfie-gram images were happily ensconced in the safe-place-for-artists that is the new Artspace Aotearoa. But Artspace Aotearoa’s safe-place ethos automatically evokes a sort of institutional empathy ransom that Ulman’s work does not need.

As a dominant feature of her photo art, Matila-Smith’s plus-size body-type invokes judgements and imperatives, which in this country are of a sort that are increasingly brought to bear on art criticism and other social and cultural discourses. This is a post-critical force invoked by the messaging and ideological positioning, which in respect to Matila-Smith’s art, have become the focus of disability studies, fatness scholarship (yes, there is such a thing cf. Charlotte Cooper, Fat Activism: A Radical Social Movement (Bristol UK: HamerOn Press, 2016)) identity theory, race studies, and decolonisation theory.

In other words, art has become embroiled with an anti-critical force that the US-based British-born poet Alice Gribbin recently identified as “art’s big empathy racket.”

In her provocative, widely read essay The Empathy Racket, Gribbin argues that “the pious and dreary insistence on heightened empathy as a proper or desirable response to art is made only by those with a stunted understanding of what art is.” (https://alicegribbin.substack.com November 3, 2021)

Of course, the highly politicised and deeply impassioned clusterfuck reaction to Mercy Pictures’ ill-fated exhibition People of Colour (2020), is nicely characterised by the last bit of Gribbin’s quip.

Gribbin continues: “The empathy racket and the political activism now ascendant in contemporary arts and letters are parallel phenomena. Both are utilitarian. The empath and the activist regard art fundamentally as a delivery system for messages and awarenesses. They believe that the output of an artwork, its effect on audiences, can be controlled and predetermined. According to both frameworks, we should be goal-oriented in our thoughts and feelings when visiting a gallery or opening a book. Our responses matter to the world. The well-being of society is at stake.”

Later in her essay Gribbin interrogates American scholar Paula Marantz Cohen, who in her book Of Human Kindness: What Shakespeare Teaches Us About Empathy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021) contends that William Shakespeare was not “complicit in the exploitive, imperialistic nature of his society,” as is it has been claimed by some scholars, but rather “the plays, read chronologically, exhibit their author’s growing awareness of the ‘inequities and injustices’ of his era.” In fact, Shakespeare’s “… plays are ‘primers to awareness and empathy in us,’ ‘a spur to revision and change.’” Feelings engendered in her by the plays’ characters, Cohen writes, “made me a better person.”

But Gribbin is not buying that:

“Shakespeare should be central to the academic curriculum, [Cohen] argues, and I would argue the same. Criticism of the empathy racket can sound like criticism of the subject of an empath’s passion, and of passion itself, and of empathy. But the reasoning behind the default to empathy is what’s shallow and deadening. Indeed, Shakespeare gave action and voice to some of the most complex psyches—frequently pathological or violent—in all of literature, so penetrating was his insight into the human mind.”

Some of the strongest most incisive art today resists and violates the earnest virtues of the empathy racket, and it shows. Last year, the French filmmaker Julia Ducournau, whose outrageous ‘horror’ film Titane, won the coveted 2021 Cine de Cannes Palme d’Ore. Ducournau was only the second woman director in the festival’s seventy-five year history to win the coveted prize.

In a highly criticised scene, the film’s erotic dancer protagonist Alexia (played by the fabulous Agathe Rousselle) finds that after having weird-sex with a muscle car (a scene later repeated with a fire engine) she has fallen pregnant when dark engine oil oozes from her vagina and breasts. The film is a harrowing mix of violence, murder, sexuality and pathological androgyny. In her Palme d’Ore acceptance speech Ducournau thanked the Spike Lee headed jury, applauding them for “recognising our hungry, visceral need for a whole inclusive and fluid world, and for letting the monsters in.”

But going against the empathy racket can be treacherous. Gribbin cautions: “Denouncing the empathy racket is tricky because it comes across as callous. In our time, virtue is a matter more of public expression than of private action.”

In other words, according to the empathy racket, the world needs art that makes people feel better about themselves, lets their stories be heard, and lets their diversities and identities be recognised and acknowledged in safe and uncritical milieux. On the surface, this is a valid, righteous and worthy sentiment, but in the hands of wokefishing activists, any failure by artists and critics to publicly express empathy for the historically disenfranchised, will result in fervent retaliation. Aka ‘cancellation.’

Any resistance to the empathy racket by defiant artists, critics, curators, gallery directors, editors and sundry heretics will be met with ardent reprisal, although this trend seems to be abating. Still, older intractable art world offenders had better abandon their residual nostalgia for a time, now past, when they were sovereigns of their own discourse. They need to accept that there is a new order in art. Resist if they dare, lest the social media outrage machine switches to ‘cancel now’ mode and they find that they have been deplatformed, forever. That is, at least, how the threat is intoned.

However, with social-media outrage becoming a dated overused tool by those seeking power, the will to cancel now seems to involve covert operations enacted by behind-closed-doors-whisperers, quietly finding new ways to disempower anyone who offends or obstructs them.

Yet on the walls at Artspace Aotearoa, Matila-Smith’s images of a lonely overweight Pasifika woman do not need to be upheld or protected by any empathy racket. They do not need it.

Whereas Ulman is a slim, pretty, white woman, who is now an internationally successful artist, lightly tripping between Europe and North America, and despite the satirical tenor of her work with its implied ironies, her career successes and sartorial care nicely amplify an image of white privilege, both racial and economic. But the divergent political trajectories of Ulman’s and Matila-Smith’s work intersect in one very important way: the selfie both artists equally render them the hostages of visual codes that cut across their own distinct cultural milieux, yet both converge in the discussion of a social media environment where the psychological consequences of constant visual surveillance can be equally brutal for everyone.

Of course, the selfie part of I Think You Like Me But I’ve Been Wrong Before would make a completely different different work and evoke quite different sentiments, entail quite different pathologies, and conceal quite different narcissisms, if Matila-Smith were slimmer. A similar reversal would be evident of Ulman’s work and invert its pathology if she looked less white, was a garment size XXL, and plain.

This ties in nicely with the species of French theory that states that the meanings of social narratives are relative, they are not universal. Social and cultural values are not innate, nor are they sovereign. The values upheld by sovereign narratives are fixed only by the cognitive biases woven into the symbolic fabric of the particular culture or society. When a cultural entity becomes so transfixed with its own self-importance, to the extent that it wilfully obstructs voices, narratives and histories that contradict and diminish its own ideas about the world, then there is nothing left to do but bring down the whole damned house of cards.

Yet Matila-Smith’s attempts to inculcate her work with “… ingenuous expressions of wistfulness and deadpan humour,” as her exhibition catalogue suggests, does not give her complete psychological and intellectual immunity from the widespread cognitive biases about the body-look of women; nor does it give her any reprieve from the brutal social doctrine that body size does matter.

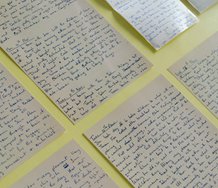

Without doubt, Matila-Smith’s process is elevated by her texts, without which her images would float in the uncertainty of depersonalised space, untethered to any semblance of truth. What the humour and intellectual honesty of her words do tell us, is that her perversity reinforces the idea that nothing about the way we look and hold ourselves up as in a public domain makes us immune to its brutality.

Matila-Smith’s body shots are too canny, and her short-form texts too smart, to get caught up in any cultural protection racket anchored in empathy. She doesn’t need it and her selfie shots are strong enough to stand up by themselves. By carefully framing the lens and veiling any unflattering parts of her body with fine lingerie, she sexualises her whole look and thereby owns it, albeit wistfully and with a slight whiff of contrivance. With her own peculiar blend of sensitivity and defiance she makes otherwise untoward parts of her body into features, not flaws. This is a process that plus-size garment advertising is beginning to understand—plus-size sexuality.

Terrence Handscomb

[1] Rachel Handler, “You Don’t Know Amalia Ulman: The enigmatic artist cast herself and her mom in her new movie, El Planeta, set in her hometown. She swears it’s fiction.” Vulture, September 24, 2021; https://www.vulture.com/2021/09/who-is-amalia-ulman.html.

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.