Terrence Handscomb – 16 April, 2021

History has treated Apple kindly, but like many artists, who in their own time have struggled against it, Apple is only beginning to admit that history is now on his side. Many of Apple's early efforts are fantastic, but this history becomes diluted when, by repeating earlier motifs, he deems to recall the frantic power that once drove him.

Christina Barton

Billy Apple® Life/Work

Illustrated, pp 390, hardcover

Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2020

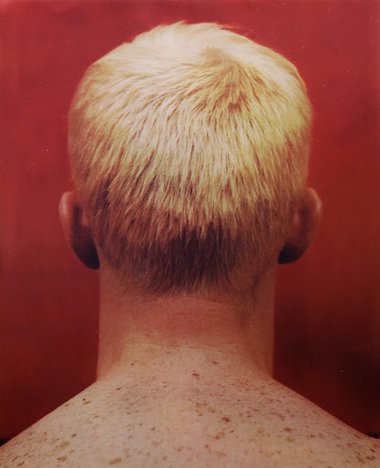

It is widely understood, by anyone who knows him, that Billy Apple is a control freak. His discerning design ethic, his minimalist aesthetic, his obsessive attention to detail, his ruthless control of space, and his cunning art politics, are all tightly controlled. This is how Apple makes art. His art-making processes, the materiality of his practice, and the adroitness with which he controls his own personal narrative, are evident in a number of books and essays about Apple, his relationships and his art.

Christina Barton’s excellent new book Billy Apple® Life/Work is no exception. But unlike other texts, her biography evinces Barton as an extremely determined and capable art historian. The book attests to her belief that the value and worth of art history lies in attention to detail and a sort of well-disciplined forensic honesty. These separate principled art history from the glowing hyperbole, brutal criticism and subjective exaggerations that characterise many other types of art narrative.

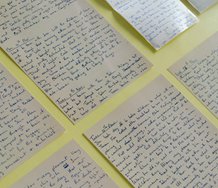

That Barton is an art historian means, for her at least, that speculative narratives about artists and their work must be backed up with historical evidence. Billy Apple® Life/Work is a vast repository of archival documents, interviews and the artist’s person objects, woven together to form a finely tuned history of Billy Apple and his work, ten years in the writing.

Much of Barton’s research has been gleaned from Apple’s extensive archive, which is housed in a large warehouse that Barton simply identifies as ‘The Warehouse.’ Barton devoted the entire prologue to The Warehouse and the significance this archive holds for art history.

Over the years, Barton has had direct and unfettered access to The Warehouse, a mark of privilege and trust that Apple has afforded few others. Billy Apple® Life/Work is loyal to this trust and this is attested by Barton’s comprehensive take on Apple, which has clearly matured after many hours spent working through his archive.

In the preface Barton writes:

‘… I seek out threads and through-lines which tap the artist’s deeper motivations that are tied up with his decision to change his name and operate as a new kind of artistic subject.’ (vii). In this respect the ‘… book’s prologue and epilogue stand apart from and frame Apple’s story.’ (ibid.).

In this Barton signals her intention and to critically examine Apple’s unique subjectivation - the formative power of an artist to build and control a representation of themselves—which in Chapter One Barton isolates in its nascent form. By selecting pertinent research fragments Barton builds an image of the artist-as-subject that will become Billy Apple.

In a 1960 memo to the Registrar of the Royal College of Art—where Apple was a student at the time—one of Apple’s teachers, Richard Guyatt, observes of the young artist:

… [Apple] has a personality which will always put people’s back up and I think it is interesting that whereas he will, if allowed, sit for hours wasting Andrew Vernay’s, Franki’s and my time discussing his ideas for the future and his innermost thoughts about his work and his life, he obviously cannot talk to people who know about this subject and therefore are in a position to criticise. In fact, he has an outsized inferiority complex and this results, as it does in many peoples, in making him self-opinionated, rude and his own worst enemy. (35)

This sort of documentation strengthens the suggestion that the transition from the artist formerly known as Barrie Bates to the artist known as Billy Apple was as much a psychological necessity for the artist as it was a definitive career move. Apple needed to control his own narrative.

Citing historical evidence of the art-student personality of Barrie Bates not only propounds the subjective condition that betokens Apple’s shift from commercial design training to fine art—the principle theme of Chapter One—it also suggests that Apple had discovered how he could control his own personal narrative by forcing it to become a crucial element of his work. Subject became object.

Towards the end of that chapter Barton points out that Apple’s engagement with commercial art and design was quite different from many of his artist contemporaries:

‘Where artists like Hockney drew on mundane and commercial sources with an irreverence that pokes fun at art’s formal pretensions, they nevertheless still maintained the distinction between art and advertising. They treated everyday sources as subjects for their painting. But Apple made marketing and commerce his very subjects … he collapsed the distinction between art and its material conditions in ways that refused art’s specialness.’ (66)

Although Barton does not say what she exactly means by ‘subject,’ and that the subject of Apple’s work seems to be both the subject matter of a work and the artist-as-subject, it is still plausible to consider how much of Apple’s work speaks to the idea of an objectless subjectivity in art—such as the more abstract notion of the corporate brand. By blending subject and object, Apple deftly loosens a sort of definitive narcissism in which an ambiguous subject is absorbed into a perpetual playback loop instigated by an uncertainty as to what is object and what is subject. We never know what part of the work is accomplished art or what part is Apple’s narcissistic deferral.

This play is imbued with Apple’s cleaved refusal to distinguish between the artist and the objects that an artist makes. Although Apple’s practice usually leaves behind a material object for art dealers, collectors and history to engage with, the old Marxist idea of spectral value is never far from Apple’s corporate works. The ghost of surplus value still requires a ‘thing’ upon which to hang its mystery and thereby make itself real in the world.

By blurring the distinction between artist and their produced objects, Apple reveals a deeper subjectivation. In his corporate work he is able to coalesce subject and object to the point whereby any critical evaluation of his work means that Apple’s well-known intolerance of criticism cannot be effectively personalised without a critical unpacking of the work; work that comes prefaced with a dominant narrative that is difficult to contest because it allows for very little epistemological slippage. This is the principle efficacy of commercial branding: leave no room for doubt. But this is no power play in the traditional sense. It is a cleaver masquerade in which the control of a narrative is reinforced by a sort of non-real or simulated hegemony of meaning.

Amongst his final writings—The Agony of Power (Semiotext(e) 2010), Carnival and Cannibal (Seagull, 2010)—French philosopher Jean Baudrillard explores theoretical themes remarkably similar to those that appear to run through much of Apple’s 1980s and 1990s work. Baudrillard points out that ‘Hegemony works through general masquerade, it relies on the excessive use of every sign and [in] the way it mocks its own values, and challenges the rest of the world with its cynicism.’ (Baudrillard 2010, 35) ‘This is the total masquerade in which domination itself is engulfed.’ (ibid., 36)

By visually minimising much of his work to sets of simple signs, standardised typography, a determinate palate and a seemingly transparent approach to content, Apple has throughout his long career, been able to maintain a narratological dominance that has been difficult to budge, let alone critically diminish. Because of this Apple has been able to conceal something much more menacing: a strategy that has ransacked the play of parody, irony and self-mockery in art and replaced it something else: narratological hegemony. This is masquerade at its best.

In a certain sense Apple presages Baudrillard’s thinking when, in his transactions works he refuses to sanitise or romanticise the buying and selling of art. He does not remove the invisible links that contemporary art has to capital, he mocks them and exaggerates them at exactly the same time that he appears to honour them. In this work, Apple appears to simulate the act of capital exchange at exactly the same time as he makes it a real transaction.

Apple sets a trap for the art world in which he is both the bait, and its prey. His cleaved manipulation of signs and significations tells us that the relationship between art and money is only a semiotic game in the field of commodity exchange. It’s all just one big simulation. However, Apple accepts just how serious this game is because: “the artist has to live like everyone else.” (292) In its time, Apple’s commodity exchange work formed a new species of art that had escaped postmodern nihilism only to find a happy home in the new neoliberal economies.

Apple’s art practice mixes his own unique blend of cynicism and personal validation. Any other way of seeing his art is either abolished, removed or made meaningless by the tightness of the story it attempts to tell. This is what the adman does: tighten the narrative until its veracity appears to be self-evident and therefore unchallengeable.

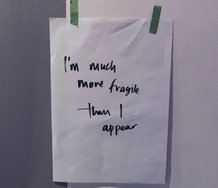

But the underlying fragility of his narrative became evident when, late in his career, a new generation of artist bustled-in-close to occupy Apple’s, until-then, uncontested narratological space. This became evident when some of artist Daniel Malone’s notorious art interventions targeted brand Billy Apple®. Malone famously threw a brick through the front window of Adam Art Gallery, which Apple had previously cleaned as a reenactment of an earlier work. To further aggravate Apple, Malone appropriated the name “Billy Apple” ‘… as his legal identity to circumvent regulations pertaining to his residency in Poland.’ (300)

Through a number of such interventions and provocations, which Barton fully discusses in Chapter Six, Malone ruthlessly baited Apple’s legendary artist ego, if only to demonstrate, quite adequately, just how easily Billy Apple® the brand, could be reduced to a symptom of its author. Such is ‘the compulsive logic of single authorship,’ as Barton put it (ibid.), when artists’ egos contend to occupy the same space.

❦

Barton though is quick to point out that it is a mistake to emphasis Apple’s corporate works, and especially his commodity exchange works, over and above the rest of his corpus. Such a narrow focus, she argues, occludes the breath and complexity of the artist’s vast oeuvre. Early in Chapter Six, Barton laments that the important survey exhibition As Good as Gold: Billy Apple Art Transactions (Wellington City Gallery, 1990), which focused on Apple’s 1980’s work, ‘elegantly summarised the key shifts the artist executed in the 1980s … but the exhibition … had the unfortunate effect of obscuring the deeper continuities with his site-based interventions and severing any vestigial links to those aspects of his output that engaged the mundane practicalities of his everyday life or spoke to a history of experimental practice which eschewed art’s commodification.‘ (291). A further annoyance to Barton is that some of New Zealand’s principle art critics, at the time, cemented this error with the perception that Apple is a ‘… the managerial artist par excellence’ (Justin Paton) and ‘… a slick operator keen to exploit the system, ‘a corporate man’, as journalist Patrick Smith called him.’ (ibid).

Although this reads like the miffed art historian scolding lazy critics and urging untutored viewers to look deeper than Apple’s corporate and commodity exchange works, Barton makes a good point. The depth of Apple’s oeuvre is considerable. Nevertheless, Apple’s corporate and commodity exchange works remain his most recognisable, critically incisive and politically savvy, and in this respect, they exceed his later space intervention and conceptual works. Apple’s early interrogations of space, image and subject - Head Height, 1964, Floor Scrubbing, 1971, Cleaning: WindowPane, Negative Condition Situation, 1973—remain amongst some of the best examples of post-object art made by a New Zealand artist. But Apple’s later considerations of space (Window Cleaning, 1971/2008, Adam Art Gallery), his later conceptual work (Sound Charts, 2002) and his Immortalisation works, feel like self-entitled reiterations of earlier works by a senior artist recalling bolder times and earlier victories.

History has treated Apple kindly, but like many artists, who in their own time have struggled against it, Apple is only beginning to admit that history is now on his side. Many of Apple’s early efforts are fantastic, but this history becomes diluted when, by repeating earlier motifs, he deems to recall the frantic power that once drove him. Apple is older now and Billy Apple® Life/Work tells this truth: objects and actions can be repeated but not replicated. That’s the thing about an artist’s own history: it is usually an error to presume that any attempt to repeat it will always exude the same powers that history has stratified in the past. Art is like that.

Barton’s book is an honest history, but more importantly, it is critical when it needs to be. She tells a good story and it is one that carries the reader without struggle. This is evidenced by the depth of research that supports it and the care that has been taken in its telling.

Terrence Handscomb

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

I'm profoundly shocked to hear of the death of Billy Apple early this morning. It's one of those things that ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 11:36 a.m. 6 September, 2021 #

I'm profoundly shocked to hear of the death of Billy Apple early this morning. It's one of those things that many of his works anticipated but which one personally will find hard to accept, his contribution to our art history being so considerable--and his personal presence here in Auckland so vibrant.

Condolences to Mary, others in his family, devoted friends and champions like Wystan, Anthony, Tony and Andrew, his various dealers, and Tina his hugely energetic and eloquent curator.

A massive loss.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.