John Hurrell – 21 January, 2022

Janet Lilo is a widely recognised, much accomplished artist and here—it is clearly evident—a clever curator and elegantly lucid essayist too. Her pairing of Chantel Matthews and Jacob Hamilton works exceedingly well. The underpinning theme is that of selfless love, caring, community values and mental and physical health; the processes of giving and not taking, the commitment of generously donating.

Pakuranga

Chantel Matthews and Jacob Hamilton

PONO: The potential of making something that leads to nothing

Curated by Janet Lilo

24 November 2021 - 6 February 2022

The main theme here is that of the relationship of the individual to the community, the societal codes that are usually adhered to, and the generous things individuals can contribute while receiving much in return. Of course lurking faraway in the background is the possibility that communities can make moral errors, and that dissenting individuals might have genuinely profound insights that get them into trouble; for mathematics (hand counts) aren’t automatically a pathway to truth. Yet this show is about sacrifice, and the various generous actions by selfless individuals that can help a group.

In the art context, the connection of exhibiting spaces and their contents to sincerity and truth is an old chestnut if you believe—as I do—that galleries potentially provide forums for discussion, and you assume unbackedup irony and fatuitous pretence are absent. That they are venues for straight talk.

Janet Lilo is a widely recognised, much accomplished artist and here—it is clearly evident—a clever curator and elegantly lucid essayist too. In her opening discussion of the Māori concept of pono, her extended exhibition title niftily goes: ‘the potential of making something that leads to nothing’. Her pairing of Chantel Matthews and Jacob Hamilton works exceedingly well. The underpinning theme is that of selfless love, caring, community values and mental and physical health; the processes of giving and not taking, the commitment of generously donating.

In terms of trade-off, you might mischievously wonder if these explorations of integrity and fidelity are really all about a form of potlatch (generous but self-ruining giving to gain community status) or even a version of a ‘be kind’ ethos to put oil on socially turbulent waters. Or is the notion a poetic but nihilist act, an avoidance of conventional ‘meaningful’ logic (as Lilo suggests in her mention of Francis Alys)? Or some mysterious something openly engineered to fail—an open acceptance of that possibility?

In the Te Tuhi hang the various sculptural, moving image and photographic contributions from Matthews and Hamilton lock together superbly, blending into a convincing fusion that looks at the power of communal expectations and the obliging nature of individual gifting. It showcases the nature of manaakitanga, the extending of a sustainable love.

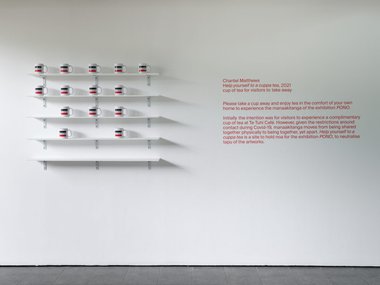

Two works by Chantel Matthews focus on the gifting. In one in the foyer, she invites the Te Tuhi visitor to take home a mug containing a chocolate chippy cookie and a sachet of Earl Grey Black Tea. Initially the foyer installation was set up to hold noa, to counter the tapu that normally prevents food and drink coming in proximity to taonga, but that plan was undermined. Because of the Covid regulations hot tea can’t be offered in the gallery building, so the gift can only be ‘opened’ by the recipient at home. As a collector of unusual mugs, cups and demi-tasses I was delighted. And I happen to like bergamot flavoured tea and choc-chip biscuits, especially when dunking. (So thank you Chantel!)

The mug, by the way, bears a cleverly worded text. Not ‘Help Yourself’ but ‘Help Your Self’, acknowledging the value of self love. It suggests, do yourself (and me) a favour; let me give you something that nurtures your body and mind. Initially it would have declared here is a normally forbidden treat to have specifically in a gallery space.

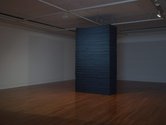

That subtle tension between individual and community via ambiguous language carries on in the big Te Tuhi room which is in darkness and features a central ‘tower’ of 26 dark green mattresses, stacked up high. After the show these will be donated to the artist’s home community in Whāingaroa to assist in protocols of hospitality. Like Matthews’ Help yourself to a cuppa tea, this work (Bad dreams and fantasies) is multi-directional emotionally. The stack can be seen as ominous, a vertical symbol of surveillance, some sort of panopticon. Or it can be seen as simply about night-time, and ensuring guests to the marae get their necessary repose.

That type of double meaning comes out again in Matthews’ video Kawa, which shows a young woman eating the leaves of a kawakawa plant. Does that action mean she is taking it as medicine or likes its herbal flavour? Or with the title, is it a comment (an acceptance or even a critique?) on Māori protocol or custom: the eager devouring can be interpreted in two opposite ways.

In her installation Wai-rua, Matthews has a line of 33 white clay vessels running round the perimeter of the room, halfway up the wall. Each mug is glazed with Whāingaroa te Moana (seawater from Raglan) while collectively they also represent the spinal vertebrae that horizontally support the roof in a whare, so the emphasis is on the interaction between the environment and the community.

Matthews’ work references the female body, namely the womb, or tangata whare, and each vessel with its flattened handle has a hint of the female organ. Plus it is positioned opposite another installation, Tides of Life, featuring ten lines of suspended, period control, underwear: 65 green knickers.

The segmented backbone of the whare, separated and spread out along little shelves, leads us out into the yard where a major contribution by Jacob Hamilton is very evident. Inspired by a kīwaha by King Tāwhiao that extols in times of crisis, the merits of building your own house of the cheapest materials, Hamilton has scavenged scrap wood from assorted sites to build a very rough, very draughty, small wooden dwelling that has an unnerving beauty in its seemingly haphazard organisation of angled walls and roof-with three windows and ill-fitting door.

Hamilton’s project fits in well with Lilo’s intermittent discussion in her essay about hauora, the notion of collective health, for that concept embraces the whare as a symbol, with different walls representing four different types of well-being. Hamilton’s rickety little shack, Rāwhiti-mā-raki, is an amusing very physical contrast to the online mental trope elucidating life enhancing philosophical principles, aiming at individual and community happiness.

In another of the smaller galleries Hamilton has two works. One is a photograph of some uncleared bush near a suburban housing estate, entitled Between A Main Road and New Housing. lt looks at the issue of the country’s alarming shortage of houses, a crisis where Māori and Pasifika families bear the brunt, and where the title has a sly twist, the ‘main road’ being the most prevalent situation nationally.

The other work is UTU, a row of receipt regurgitating machines, ten lined up along a wall, occasionally spilling streams of tumbling paper down over the floor. The title can mean revenge or it can mean restoring balance in a less heated way. The paper presents historical documentation of Māori / Pākeha land transactions, texts and images, some decipherable, others not; some ethical and fair, others scandalous.

In an odd way UTU and Tides of Life are bookends: horizontal installations with liquid allusions. One has real paper tumbling vertically like a waterfall, demonstrating the multiple forces of racism and profitmaking through land sales and reselling, urged on by greed that is seen as ‘normal,’ piling up on the floor.

The other is thwarted motion implied in a reference to nature and descent—and kept unseen—and actually ineffectual (no good for heavy periods) but no matter. Just as Hamilton’s UTU and Between A Main Road and New Housing in the far room team up like tag-wrestlers (one work in two parts), so do Matthews’ Wai-rua and Tides of Life—but these teams are not competing. They all dance together in effortless co-ordination.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.