Brendan Jon Philip – 25 March, 2018

As a programme with no specific requirement other than the vaguely defined onus of some kind of exhibition, the University of Otago Frances Hodgkins Fellowship has an apparent tendency to attract work that comments on the nature of the residency process in itself. Diaristic and self-reflexive modes of expression emerge as the most direct response to questions of a set timeframe with no set outcome, and the duration of the artist's stay in Dunedin becomes a lens of self-examination rather than the means of achieving a specific project.

Cycles and patterns of time weave themselves through Campbell Patterson‘s end-of-residency show, toot floor, finding the artist marking the days spent in studio with a teasing existential horror of the recurrently mundane. As a programme with no specific requirement other than the vaguely defined onus of some kind of exhibition, the University of Otago Frances Hodgkins Fellowship has an apparent tendency to attract work that comments on the nature of the residency process in itself. Diaristic and self-reflexive modes of expression emerge as the most direct response to questions of a set timeframe with no set outcome, and the duration of the artist’s stay in Dunedin becomes a lens of self-examination rather than the means of achieving a specific project.

Such a survey of a year can be unfocused in nature, while the work presented as a document of the search for focus can seem rather token and floundering for meaning. This introspective/explorative mode fits very neatly into the absurd meditations on the everyday characteristic of Patterson‘s practice and his search for meaning—or refutation thereof—and so seems adroitly suited to residency methodologies.

That is not to say that the work persistently lacks focus, but that the search for focus, often futile, is deftly expressed in it. In constructing his confessional document as a paean to the abstractions of boredom, the artist’s practice is just one more piece of mise en scene for the facile, orchestrated performance of commonplace existence.

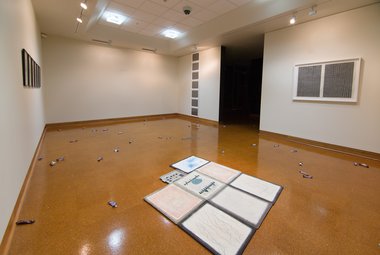

Essentially dressing the stage, crumpled Snickers chocolate bar wrappers and scattered grapefruit seeds are strewn throughout the three rooms of the exhibition. Speaking to the everyday detritus in which Patterson attempts to ground his aesthetic voice, this installation tactic both plays upon and falls prey to bad art jokes. Patterson is performing the role of the indolent student showing their studio trash as a last minute submission to a major practical assessment. Thought of as comedy, the absurdity here tends towards bleakness, the indulgent pleasure of chocolate being negated through repetition, and habitual pleasure the mask of intemperance as pathology. The grapefruit seeds do little to negate a nutritional indictment against the bohemian bad diet.

The first proper work one encounters is singapore a/c studies (all titles are deprecatingly uncapitalised), a jumpcut digital video with an over-amplified soundtrack of public toilet stalls in Singapore shopping malls. A series of still shots of nondescript, institutional architectural details flash by at an irregular beat, the audio of an incessant air conditioner drone cut to a slow staccato.

Patterson invokes the bathroom as a place of retreat into solitude amidst the public arena of the everyday. No sign or sound of people is evident, and notably the artist himself is also absent—as with the series, call sick, completed during the first part of the Fellowship, and shown at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in June last year. This absence of human subject presents the tension between public and private space as more of an interior condition than faux naif vulnerability—unlike his previous gestures towards the modalities of performance art.

The other video work in the show, old style pathetic, is a digital version of a VHS recording of lit tea candles burning outside the residency studio from night to day. As with singapore a/c studies there is no duration listed for the video in the exhibition catalogue, Patterson wishing the viewer to encounter the work momentarily and experientially, rather than as a piece of linear narrative. In my visits to the exhibition the video was only in the night cycle, although I was assured it plays through to the day. As it was, the candle appears as holes punched in a darkened film, flickering and undefined in the analogue noise of dirty VHS tape. Ritualistic associations of multiple burning candles break down into quotidian habits under the artist’s gaze. Ritual, after all, is just formulated action invested with meaning; another absurd mask for humanity’s performance on the stage of meaninglessness.

In the back room beyond is a series of stark monochrome linocuts, each titled exterior and numbered, although wilfully presented out of sequence. The subject of these works is plastic food in various states of collapse and flattening. A snapshot of the final stage between supermarket shelf and landfill, these images resemble photograms of fossils: skeletal objects placed directly on the photosensitive material with the chiaroscuro of their forms emerging on exposure to the light. The most traditionally technically polished works in the show, these pieces demonstrate Patterson‘s adroit picture making. There is a sensitivity to line and light that transcends the subject matter. It is almost enough to lend an inadvertent redemption to the relentless flailing in a void of consumer detritus.

A divergent approach to printmaking on the opposite side of the exhibition, blue 2 consists of six unique colour photocopies. Each image is a similar arrangement of the same basic visual elements—loose, unselfconscious doodles made during late night telephone conversations with his partner overseas. These drawings are used as printing plates of a sort, copied sheets run through repeatedly, layering up to a series of composited images. Deliberately out of register, the slight shifting of visual elements deftly emphasises this manual and mechanical process giving a sense of embodied labour to the use of a machine. The play against technologies, using things in ways they are not meant to be used, echoes digital presentation of analogue process in the video work old style pathetic. Alongside the linocuts it points to possibly fecund new fields of investigation for Patterson’s practice.

Across the room from blue 2 abject tedium reasserts itself with apathetic drums i and ii. Unruled pencil drawn grids calendar out time, first in days and weeks and then in minutes and hours. These squares are filled in by a rough circle of intense graphite, marking the passing of each unit of time, and apparently created as a response to the task of quitting cigarettes, an undertaking that may also account for all the chocolate bars; freedom of choice expressed as trading one addiction for another. The addict counting days clean is seen to approach the passing of time like a prisoner marking the stretch of their sentence. The calendric grids are replicated and mirrored, the unevenness of their structure unfolding through symmetry into pattern, both drawing attention to and subsuming the variations in composition. Deviation is not permitted to become difference as we find that the problem is not that each day is exactly the same, but that each day is not distinctive enough in itself.

Finally the title work toot floor is an assemblage of painted doormats with a few miscellaneous ingredients mixed in more for texture than chromatic flavour. As paintings the works are like an accumulation of grime, ordered aestheticised collateral stains that mark the trace of time on mundane objects. Wrestling with unmalleable materials this way underscores Patterson’s stated intent of aestheticising the boredom of the everyday. The outcome feels uncertain as to whether it wants to revile or revel in directionless tedium.

Malaise and ennui are positioned centrally in the untitled publication accompanying the exhibition. Published in an edition of 153, the book is 80 pages of short declarative sentences rattling through the vacuous minutiae surrounding an unnamed female protagonist. She does this, and she does that, and nothing actually happens. Less diary, more catalogue of inconsequential events, the particular aimlessness of the narrative provokes an existential horror at the surrender of agency.

Submerged in the flattened affect of the everyday—in a post-truth world of fake news and alternative facts—toot floor walks a fine line between meditative emptiness and nihilistic abandon. The collision of creative activity and commonplace apathy, across multiple avenues of enquiry and technical proficiency, reiterates the same tale of meaninglessness and futile resistance. The exhibition is an institutional document of drifting as much as exploration. Clearly formed, Patterson’s aesthetic practice confronts the terra incognita of the overlooked with an anxiety that is functionally dysfunctional. While perhaps not quite finding a new thing to say but a newer way of saying the same, the time spent in the residency—more productive than he would care to admit—has successfully allowed the artist to move forward, while commenting succinctly on work that has gone before.

Brendan Jon Philip

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.