Mark Amery – 29 April, 2011

Like Hammond, each painting presents worlds within a world. Be they clouds or bubbles containing landscapes and buildings, they are crafts floating out in space. And that space, the work's earthly humour reminds us, is really the artist's dream world.

I’ve previously been lukewarm about Matt Hunt’s paintings as presented in last year’s Ready to Roll at City Gallery. Clever and appealing with their potpourri of influences for sure, but as narrative paintings they didn’t visually cohere enough for me, or have a strong enough sense of vision to make me want to keep coming back.

Hunt’s grand scheme is promising: visions of an apocalypse brought upon humans in their mistreated world, with a heavenly promised land out in space (complete with angelic animals and devilish aliens). The works stitch together numerous overarching stories within art historical visual architectures - from the Bible to Star Wars - and spin them into surreal and comic pop cultural hybrids.

I’ve previously struggled to find the same sort of conviction I’ve found in many other so-called outsider artists’ cosmic, futuristic or apocalyptic visions, that usually synthesise religious and pop cultural imagery (American Royal Robinson is a prominent recent example). Unlike the grand pictorial visions of Bill Hammond, to which they owe much, Hunt’s work also didn’t make me feel anything. Partly that came down to technique - his application of paint often flattened rather than brought life to his visions.

Hunt’s second show at Peter McLeavey however feels like a big leap forward, answering some of this criticism. Comprised of three large paintings, it shows a far more confident painter developing, both in vision and technique. The paintings elevate you. They are full of vigour, both in the coherency of their visual structure and movement (generally upward or outward, in both the gesture of their figures and the bigger action), and the focused strength of their feeling and storytelling.

The new age that Hunt depicts is still an identifiable amalgam of adopted ideas. Everything from William S Burroughs and L Ron Hubbard to the epistles of St Paul informing the work (it’s Burroughs drawing of the biblical and the past into the human present that comes out strongest for me). The works remain collages of appropriated art and popular historical visual structures, from Tintoretto to McCahon, but all brought together with a grand baroque swagger.

Two of these works present high vaulted interiors: cathedrals open to the universe above and beyond, full of grottos, screens and windows offering different scenes, and a multitude of levels upon which Hunt’s characters can play out dramas, allowing the artist to shift between references. Like Hammond, each painting presents worlds within a world. Be they clouds or bubbles containing landscapes and buildings, they are crafts floating out in space. And that space, the work’s earthly humour reminds us, is really the artist’s dream world.

These paintings manage to be full of humour (picking out the ironies of how we live and what we believe in - or don’t - today) and passion. In Memory of the Sacrifice Hunt audaciously places Jesus on the cross in the centre. Winged like an angel, Jesus’ head is replaced by a washing machine, watched over by a Botticelli-like angel with a camcorder for his head. Nearby, also in midair, a white horse-headed angel diligently steam-mops, washing away the sins of the world.

The weakest work for me is Church of Refuge, but even this achieves an elevation most previous works have lacked. At the bottom is an awkward and static bringing together of differently scaled animals and celestial beings at a Star Trek-like teleportation station. Star Trek’s humanism, in bringing together humans and aliens, comes through strongly as an influence in this show.

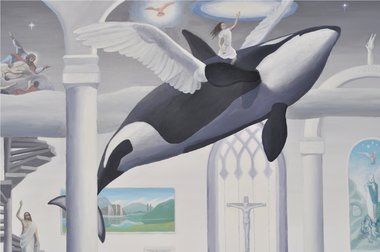

In the upper reaches of the painting things however lift off. Midway down a spiral staircase (we are directed to this from below by a saint) Jesus is providing a blessing. Above God appears a young woman armed with a paintbrush - Sistine Chapel-like from the clouds and centre-stage - soaring on the back of a winged whale. It feels emblematic of the artist’s own blessed sense of freedom in the creation of new worlds.

Scenes like this convey an infectious hope and elation. The artist’s strong conviction comes through in a way that it hasn’t previously. There are a number of visual references to McCahon (notably a rocket-powered crucifix in Memory of the Sacrifice) but it’s more in Hunt’s push to communicate faith and feeling with the props he’s given himself, that makes McCahon such a strong reference point.

The strongest painting here by far is Supereality. An apocalyptic set of riders fly out of the picture, an amalgam of animals and war aircraft, joined by flying chunks of text (‘Supereality!’ and ‘Diamond Dreams!!’). In look and tone this evokes the futuristic marketing aesthetics of the 1970s. Like a blast from a celestial trumpet the painting speaks of a blissful utopian state we can float in, out there beyond our current existence. In the surround and background is the cosmos - all with a sense of past, present and future - colliding within a prism with shards now coming back together.

Like that transparent prism with its strong colour and composite perspective, Hunt’s ideas - from many different angles - coalesce into one forceful statement. His text running across the top of the painting proclaims that the ‘stars of the new age’ will be the saints who accepted Christ as their savior: “They will shine like stars in the all new federation of multidimensional states of being.”

Mark Amery

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.