Warren Feeney – 28 July, 2011

In the wake of a cold, wintery city with rising unemployment, whose essential infrastructures and buildings are now appearing to be up to four years away from being fully re-established, it is the seriousness and sincerity of this show that makes it so welcome in Christchurch.

Christchurch

Annual Ilam Sculpture Exhibition

Heavy Pattern

20 July - 22 July 2011

If you were looking for a touch of irony or humour then Heavy Pattern, the annual sculpture exhibition by senior students at the Ilam School of Fine Arts will disappoint. This is not an exhibition that artists like Richard Maloy, Eddie Clemens or Steve Carr, for example, would feel at home in. Heavy Pattern is the SFA’s 18th sculpture exhibition and it is heavy - serious in its content, intentions and consideration of the place of art in the grand scheme of things.

Possibly, the demands of finding appropriate spaces in Christchurch to locate this year’s exhibition may have contributed in some small way, towards its gravitas. At present, nothing in Christchurch seems straight forward. In past years, the SFA has made use of buildings within the inner city to stage this exhibition, but with few premises open, intact or increasingly expensive to lease, the SFA’s sculpture department has been forced back to its Ilam Campus. To its credit, this has made little difference to the exhibition’s success.

Indeed, in any other year, I might have felt less generous towards a group show that is defined so pervasively by its solemnity. In its engagement with materials, processes and making, as well as a general desire to consider big questions about life/nature and where art find its place in the universe, the spirit of former senior lecturer in sculpture at the SFA Andrew Drummond seems to loom large. And currently, this is not such a bad thing.

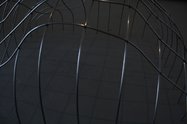

Consider, for example, Jason Ware’s installation, Untitled. This is a work that seamlessly integrates its intentions as sculptural object and a series of complex narratives. Ware’s suspended, spiraling form in the centre of the room, turning at undulating speed, pulses like a conjurer’s wand, wrestling and shaping a contoured skeletal landscape from the floor below. It seems familiar and entirely otherworldly. An act of natural creation and scientific truth reconstructed.

Works by Thomas Reveley, Ana Iti, Lana Burtenshaw, Marela Glavaš and Liv Worsnop act as more than worthy companions to Ware’s installation. Consisting of two tent-shaped pyramids, one made from the rooted stump of an oak tree and the other from ply, concrete and rope, Reveley’s Temporary Shelters 1 and 2, effortlessly span 10,000 years of human history from transient refuge to elegant architectural module. Or is Reveley simply revealing his working processes, with the tree stump as drawing and evidence of first steps towards a refined work of art? Either way, Temporary Shelters 1 and 2 is considered and generous in its use of materials and potential narratives.

The transformative nature of art through the manipulation of materials is shared by Marela Glavaš in Processional, with scattered hessian on the gallery floor in counterpoint to the circular hessian cone on the gallery wall directly above. Processional occupies and controls the gallery space, self-consciously drawing the visitor’s attention to the environment that they share and occupy with the work. It reveals much in common with Steve Walsh’s Joins, a work whose title understates the complexity of a structure that is visually demanding to read and unravel. An abstracted, three-dimensional minimalist puzzle, Joins insists that the viewer must continually re-circle the work to make sense of its structure and purpose and in doing so, Joins reveals that this may be the point of the work itself.

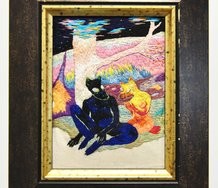

Alissa Gilbert and Mat Logan’s contributions to Heavy Pattern are more directly concerned with philosophical questions about the parameters, purpose and relationships that art establishes, for better and/or worse with individuals and communities. Logan’s carved oak Mask is rich in art historical allegory and symbolism. The burnt tree stump of Neo-romantic painting from the 1950s and an accompanying deflation of a post-war mythology about socialism and ordinary working New Zealanders are up for question and the potential of reconciliation with the world of serious art.

Gilbert’s The Shop bridges the gulf between her practice as a sculptor and a maker and retailer of organic soaps and screen printed t-shirts. With an advertisement that states ‘Come into my shop you filthy bitches,’ Gilbert’s shop does for commercial retailing what Tony de Lautour did for serious painting back in the mid-1990s. While it’s a work not without precedent, also inviting comparison with Kim Paton’s Free Store in Wellington earlier this year, Gilbert’s merchandise isn’t commercially branded. Her products retain something of the artist’s public persona, being much closer to Illicit or Misery’s posters, art work and toys. However, Gilbert’s art is tougher, niggling away at the issue of context and the art gallery as an environment that defines the status and the monetary value of the objects it chooses to display. It’s an issue that Gilbert seems determined to scrutinise further and while The Shop still seems like a work in progress, it’s an admirable idea, rich in its solemnity and worthy of further mileage.

Which is why Heavy Pattern is deserving of attention. Whether intended or otherwise, rather than playing to irony and humour, this exhibition feels like an appropriate response to current circumstances. In the wake of a cold, wintery city with rising unemployment, whose essential infrastructures and buildings are now appearing to be up to four years away from being fully re-established, it is the seriousness and sincerity of this show that makes it so welcome in Christchurch.

Warren Feeney

Recent Comments

Andrew Paul Wood

I think the spirit of Drummond is fairly dilute - a matter mainly of apostolic succession. Admittedly there are elements ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

Andrew Paul Wood, 5:43 p.m. 1 August, 2011 #

I think the spirit of Drummond is fairly dilute - a matter mainly of apostolic succession. Admittedly there are elements of it still there, and sculpture lecturer Louise Palmer was a student of Drummond, but in retrospect I think there is a more general Joseph Beuysian influence at work.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.