Mark Amery – 13 September, 2011

The rationale behind Heald's pairing here isn't hard to unlock, and its not based on this being ‘The Hofs' show (though the temptation to randomly group artists based on where they sit together in the alphabet isn't a bad one in ridding us of needless fiddly dealer curation).

Lately there’s been much cause in the arts to think of history as collapsing in on itself - or, at least the modernist ideal of cultural history following a linear progression. Just as Simon Reynolds’ chronicles recently with music in ‘Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to its own Past’, there is in art a pervasion of nostalgia and a mashing up of styles: the sense that some artists are working in ever-decreasing circles in a drawn out endgame. It can leave the viewer wondering what period the artwork they are looking at belongs to, and if such art historical judgements really matter.

This obsession isn’t all pervasive - there are plenty of artists making vital new work in unique ground, or breaking cycles rather than prolonging them - but it’s certainly prominent, and what dealers find buyers feel safest in having on their walls. Sophisticated ornaments to ignite conversation in the home, there’s much work of this nature around. Much is really interesting, but it isn’t really going to change you, or ultimately make you feel anything other than comforted and smug. Mind games and puzzles that play with fragments of received cultural knowledge, toying with you now and then.

In this regard Robert Heald Gallery has been really on the game. Engaging works that lock together well as a stable, like one big puzzle. The work here rarely moves me, but it’s often stimulating. And there’s a discernable line of investigation through various young artists work in, simultaneously, rubbing away at and adding to the fabric of the past.

On these points this current exhibition of the work of David Hofer and Frank Hofmann is very interesting indeed. It heralds what I think we’re likely to see more of around the traps: what might appear at first odd pairings of artists across present and the past, but which with smart linkages provide fresh ways into the work. Good curation? Good marketing certainly, and it still leaves the art to do the talking.

The rationale behind Heald’s pairing here isn’t hard to unlock, and its not based on this being ‘The Hofs’ show (though the temptation to randomly group artists based on where they sit together in the alphabet isn’t a bad one in ridding us of needless fiddly dealer curation).

Frank Hofmann (currently the subject of a survey exhibition at Gus Fisher) is a celebrated Auckland photographer of the 1940s and ‘50s, of whom there has been a revival of interest in alongside the increased artistic currency of photography in the last two decades. His interest in found abstraction bears interesting comparison to a new generation of photographers, notably recent Massey graduate Andrew Beck (both are shown by Wanganui’s McNamara Gallery, who assisted with this exhibition).

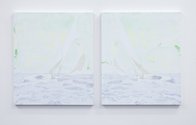

David Hofer is a recent Elam MFA graduate (works from this series were shown at Hopkinson Cundy and reviewed here). His work employs the nostalgic leisure and hobby imagery, and fruity interior decorating colours (think limes, lemons and grapes), of Hofmann’s era. The pavilion, the lido, the sailboat and the model train - dreamy sun-kissed and brightly coloured modern vehicles of escape. The play with abstraction in Hofer’s contemporary work pairs nicely with Hofmann’s modernism.

Both artists are interested in what they can do musically as a palette with this most comfortable of imagery. I’m reminded of hobby time with my father, constructing sailboats with string art (a true 1960s and ‘70s fad) and laying out model train tracks.

As if leaving impressions of memory with the touch of paint, there’s a physical lightness with content in Hofer’s work that is appealing. It’s as if with his finger he’s playing on the bedroom wall with impressions projected through the window from the world outside. The way Hofer uses the surface of the canvas for the textural impressions of paint matches in a way the impressions of light made by Hofmann on photographic paper.

Hofer’s current favoured format is a double canvas. One doesn’t so much mirror the other as acts as print block, as if its been placed against the other to create a new, fainter impression or more delicate wash. This technique suggests the way the past becomes not just fainter and more abstract with time, but more visceral - about the sensual remembrances of textures and colours.

In Untitled (Yellow Train) a train loop has become a track for tracing feelings through touch, the carriages made up of little more than a few strokes of the fingertip. Strangely it makes me think of a Boy’s Own version of ‘90s Judy Millar painting, the subject matter just a vehicle for a gorgeous meditative motioning of paint.

I prefer the work of Hofer’s which play most clearly with the forms his compositions are based on. At a distance in 1959 we see a yacht, but up close its barely there. In Pavilion, less satisfyingly, this immateriality has become a sticky residue of pattern, with little discernible reference back to the subject matter at hand. Yet the work remains at least a little engaging for its use of different, divergent methods of paint application - a gorgeous complexity found in all these works.

A similar sense of experimentation with the application of texture to source materials is found in Hofmann’s photographs. This can be shadows, projections, light and volume in arranged still lives (the overly artful Studio Arrangement from 1944 - the equivalent of Hofer’s Pavilion with its achievement of intriquingly bringing together disparate elements) or the complexity of found arrangements (the superb Gold Room Demolition (Caducity) from 1956).

Centreframe in Gold Room Demolition is a painted mural of musicians wrapped in a ribbon made out of a musical stave, time winding around them like the loops of Hofer’s train tracks. Around this we see the process of demolition, light playing dramatically over the appealing crumble of material and rhythmical piles of shapes. As a photograph it is akin in music to the inhalation and then exhalation of breath, or the moving of the bow this way and then that - time accumulating new strokes at the same time as it rubs old ones away. Suddenly Hofmann makes complete sense in the Heald stable.

As the image Corridor Cellist Cambridge Music School from the same year also beautifully meditates on, light determines volumes and impressions, creating complex arrangements which can have a musical completion all of their own.

Mark Amery

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.