John Hurrell – 4 May, 2011

Like the ‘hinged' link between the two planes in Hofer's work, Jannides has a conceptual bridge joining articulated language (that provides an origin) to experienced ‘reality' (generated from reading and transmuted into art).

We have in this two person show two painters who are sufficiently different to be effective foils in their methods of working - yet who also have an odd coherence, despite their diverse approaches to image construction and ways of exploiting properties of the imagination.

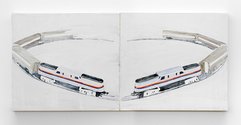

David Hofer uses found photographs (such as of trains, boats and buildings) to explore the nature of symmetry by painting images on doubled pale board panels - positioned in mirroring pairs vertically or horizontally, touching or carefully spaced apart. His paint is delicately thin, with an appealing glowing translucence, leaving the hovering, reversed, almost touching, images understated. Parts have been painted over but not totally hidden, as if the process is still ongoing. Sometimes one of the panels is tilted forward.

Superficially his work is akin to the photographs of Ann Shelton except his audience looks at the mirrored/paired imagery quite differently from hers. With her photography there is a calculated confusion as to which of the two images is the original source. The sequence of duplication is not obvious. With Hofer such questions don’t arise because there is a gestalt, the two panels merge mentally into one, and the components are much vaguer - floating and more abstract.

The term ekphrasis is often applied to where visual art is described through language, a scene or action (say in a print or painting) accounted for in great verbal detail. Milli Jannides reverses such a process by starting off with literature, finding vivid portions of novels from which she then proceeds to construct paintings. Like the ‘hinged’ link between the two planes in Hofer’s work, Jannides has a conceptual bridge joining articulated prose (that provides an origin) to experienced ‘reality’ (generated from reading and transmuted into art).

Many of her images are fragmented - not ‘realistic’ but piecemeal impressions - as if collected snippets of memory. These portions are strangely combined with perpendicular joins, as if out-of-sync reflections caught in a vertical window. Often the paint application has a feathery Bonnardlike softness, and with some imagery of awninged shop fronts there is more than a hint of dappled post-impressionism. Bits of tactile Dufyesque and Matissean paintwork also surface in her lightly layered composites.

While Hofer’s imagery is airy, Jannides is compact and darker. It is more overtly improvised, whereas his compositions arrived gradually, end up looking preplanned - even though that is not actually the case.

Because Hofer works with found images (as material aids) to make more images his paintings have a confidence and compelling decisiveness that Jannides’ - with no basis in drawing or preparatory studies, only her own imagination - lack. Their ad hoc construction needs more. It alone cannot help them become memorable.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.