Peter Ireland – 5 May, 2011

Ross's mode is “traditional” documentary, and while that approach is slowly recovering from two-decades of being largely out of favour with art curators, it's still far from being the flavour in vogue with them as well. There's not been a group show looking at the documentary since the City Gallery's significant 'Imposing Narratives' exhibition of 1989, and an awful lot of water has passed under the bridge since then.

Wellington

Andrew Ross

I last saw you there

Curated by Abby Cunnane

16 April - 15 May 2011

Two years ago a book appeared featuring the work of 100 emerging - mostly young - New Zealand artists. In terms of practice, only three of them could primarily be described as photographers: Darren Glass, Sam Hartnett and Richard Orjis - with perhaps sculptor Steve Carr flying in under the radar with his memorable photographic images. This seemed rather low representation given the rising profile of the medium over the past twenty years and its clear attraction for the young and emerging.

The book’s author, Warwick Brown, when tackled with this apparent imbalance, wrote in Art New Zealand 134, Winter 2010: “As for photography generally, I think it has most relevance when it is integrated into an artist’s wider practice. I took particular care to consider all reputed photographers who fitted my stated criteria. Those omitted were deliberately omitted - either because their work was unoriginal, boring and banal or because it was not so interesting as the work of the other artists”. Of course, “relevance”, “unoriginal”, “banal” and “interesting” are all highly contestable descriptions, and as none of them are further addressed, we clearly just have to take the author’s word for it. Horses for courses, one might say. Although it’s worth noting that Brown’s comments mirror exactly criticisms made in the later 1950s when the Pop Art phenomenon began challenging the assumptions of High Modernism.

However, this book was constructed, advertised and sold on the basis of its being a collector’s guide - those words appearing in bold type on the cover and title page. The unannounced but nonetheless clear message is that photographers per se aren’t artists and that photography qua photography is not worth buying. Even Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were over those hurdles. It’s amazing enough that such attitudes persist into the 21st century, but absolutely astonishing that they’re held by a respected art writer and - even more - go unchallenged upon their formal publication.

The new meteorite hopefully eliminating these dinosaur ideas may be slower and less spectacular than the one 61 million years ago destroying the actual creatures, but this time with a positive rather than negative effect. The work done by public and private galleries, curators, scholars, writers, editors and publishers to change widespread public perception continues apace, and it’s the combination of such forces over a number of years that brings the work of photographers to public attention, scrutiny and gradual acceptance. In this case it’s the City Gallery, Wellington, mounting this 50-print “taster” of Andrew Ross’s oeuvre deftly curated by Abby Cunnane in their Michael Hirschfeld gallery. The 50 images are arranged into 6 simple groups according to a mix of subject matter and Ross’s photographic interests spanning more than a decade, the show constituting a very well-crafted introduction to what the photographer’s about.

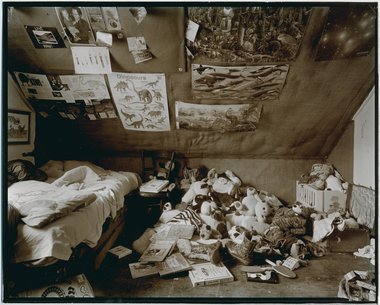

At any given time there’s a certain “look” in art production. Whether this is, in individual cases, an instance of current fashion or something with actual roots in the culture is for history to get sorted. Whatever claims can be made for Ross’s work, no one would risk terming it fashionable. It has, unmistakably, a deeply unfashionable “look”. Right now, at the City Gallery, there couldn’t be a greater contrast between this show and another photographic exhibition in adjoining galleries on the first floor: Neil Pardington’s touring exhibition The Vault, images whose subject matter is the storage areas of New Zealand art galleries and museums. The photographs are large, in colour, crisply formal images of rigorously tidy institutional storage practices in clinical unpeopled spaces. Ross’s photographs are small, black and white images of often chaotic, idiosyncratic personal or abandoned spaces. Pardington’s work tracks the respect given to the high cultures of European, Polynesian and scientific objects whereas Ross’s track takes him to where ordinary people have lived. The low culture of making a sow’s ear out of a silk purse.

Ross is in his mid 40s, has been “emerging” for the past decade or so, but as his base and exposure have been pretty much confined to Wellington, his profile elsewhere is probably not high. It’s high enough in the Capital though: he regularly shows at Photospace and his work has been published more than once in Sport magazine and the former New Zealand Journal of Photography. In 2008 Victoria University Press published a book of 51 Ross photographs, Fiat Lux, in which 5 writers and curators each selected a particular group of work which appeared alongside their respective essays. Looking at the record, it’s apparent that Ross’s work has been written about rather a lot. Much more than, say, for a higher profiled artist such as Fiona Pardington. There’s a kind of visual poetry about Ross’s work that seems to call up a writerly response. We live in a world still ruled by the myths of progress and human perfectability - all those plans, gyms and self-help books - but the world according to Ross gently queries all this, and it’s perhaps the sheer relief of recognition that triggers all this writing, just as the extremes of war triggered in the trenches such intense diary writing and letters home. Reality triumphing over myth.

Ross’s mode is “traditional” documentary, and while that approach is slowly recovering from two-decades of being largely out of favour with art curators, it’s still far from being the flavour in vogue with them and those reliant on their leadership: auctioneers, writers and collectors. Serious documentarists such as Laurence Aberhart, Mark Adams, Peter Black, John Miller, Neil Pardington et al continue to do fine work but they’re probably not selling much - certainly not enough to live on. And apart from frequent art museum shows of their work individually, there’s not been a group show looking at the documentary as a phenomenon since the City Gallery’s significant Imposing Narratives exhibition of 1989, and an awful lot of water has passed under the bridge since then.

A lot of words too. As a necessary corrective over the same period many writers have queried the faith viewers have automatically invested in the veracity of photographs, a project fuelled more recently by the digital revolution. A sort of timely conceptual wake-up call, you might say. But, despite the finest words, the most seductive arguments of theorists, untold number of photographers shooting scenes and family continue to believe that the resulting images are reliable records of something that was there, something that actually happened. The welter of words Ross’s work has occasioned tends to assume this too, as do the legions of viewers who see it.

But, it’s one thing to supply subject matter and another thing altogether to get purchase on what those images might suggest or “mean”. In Ross’s instance, there’s no debate that the image entitled Reference Room, Plan 9 Studios is a former Chinese church in Wellington’s Frederick Street, but what each viewer makes of the enigmatic collection of archival material depicted along with the computer gear and 1970s’ furniture inside a match-lined room with Gothic fenestration is anyone’s guess. Everyone brings their own history to the processing of and response to such imagery, and it’s sobering to discover how much richness can be provoked by so much plainness. It’s easy to roll out the “nostalgia” word here - maybe even “boring” and “banal” too - but it’s more about a texture that only a vividly lived life can recognize.

Another thing that distinguishes the great tribe of photographs from other visual art forms is that by sequencing them in a certain order - a la Gavin Hipkins or Haruhiko Samishima, for instance - or by marshalling them into various groupings, the possibilities of “meaning” can be amplified and extended. From February to August in 2009 Ross held the Tylee Cottage Residency in Whanganui and over the 6 months he combed the back alleys and crumbling buildings of that historic town, and, like Rumplestiltskin, turning straw into gold. From 17 September until 12 December last year the Sarjeant Gallery mounted a selection of this archive: Round & About Wanganui: 72 photographic studies. This exhibition revealed that Ross had reached a new plateau with his work, and even long-term residents were amazed at the width and depth of his depiction - characterized by typical Rossian gentleness, respect and quirky humour - finding it a revelation. Like any dot on the map, Whanganui’s a place, people live there, others know where it is - no rocket science involved in any of that - but what it is, what gives the place its individual character and texture, is much less able to be pinned down. Ross has given it a good shot. One of the most complete (and masterful) photographic portraits of a colonial New Zealand town cumulatively is William Harding’s Whanganui. Ross in his more time-focused and more wayward take is his very worthy successor.

There was talk of touring the show, but it was felt its site-specific nature would limit wider appeal. Maybe. Maybe not. Sometimes curatorial decisions are guided by considerations other than what the viewing audience might most enthusiastically respond to. In any case, none of the Whanganui work appears in the City Gallery show and it’s poorer for the absence because, as a body, it signals Ross’s major achievement to date.

Andrew Ross’s images can seem very old-fashioned, but - almost in spite of themselves - the issues they sometimes address are spookily contemporary. Their tangential but nonetheless telling connection with the environmental and sustainability movements, for instance. The recent Christchurch earthquakes have suddenly raised deep-seated psychological questions about just what the physical construct of a particular city might mean for us, and, typically, opinion has been ranged oppositionally into preservationist and progressive, the latter group championed by the local Minister appointed to oversee the reconstruction. His view seems to be that virtually anything pre-1960 should be demolished. This crude materialism overlooks completely the role the familiar has in knowing where we are, and, even, who we are. The great film-maker Bunuel once said that “Our memory is our coherence”, and the photographic tradition has this perception close to its heart. Memory is not a web of the significant but a net of the familiar, and Andrew Ross is its poet laureate.

Peter Ireland

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.